22 January 1818: Reading King Lear & Changing, Ripening Intellectual Powers; Keats’s Reality Principle

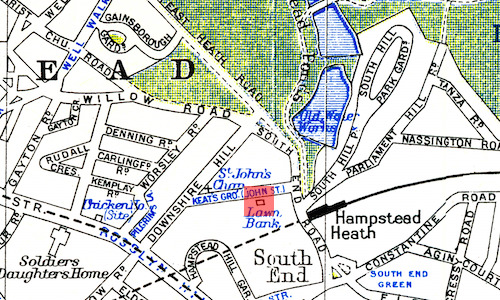

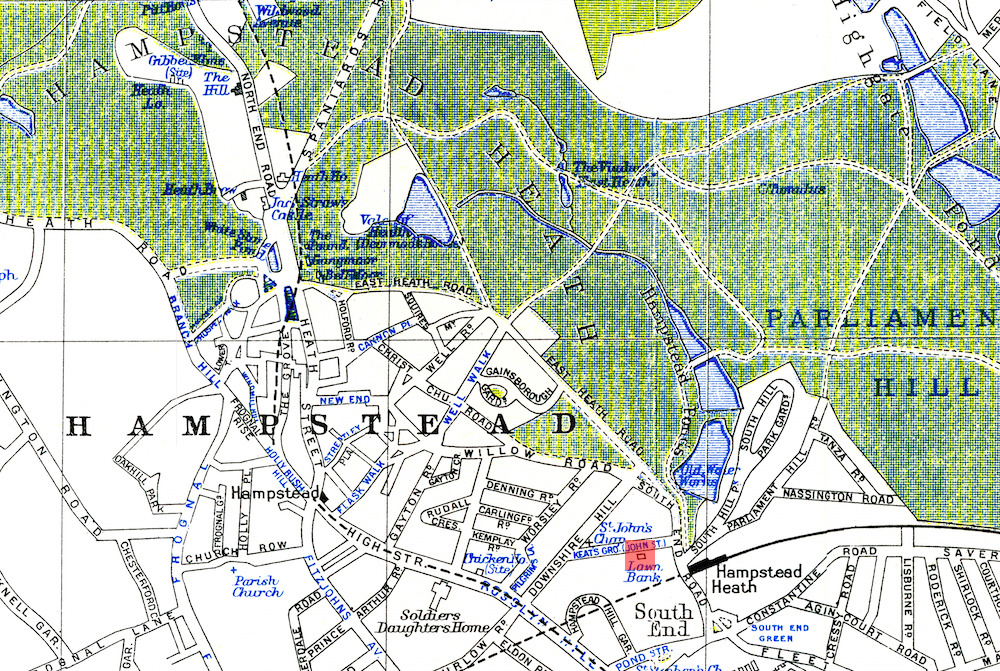

1 Well Walk, Hampstead

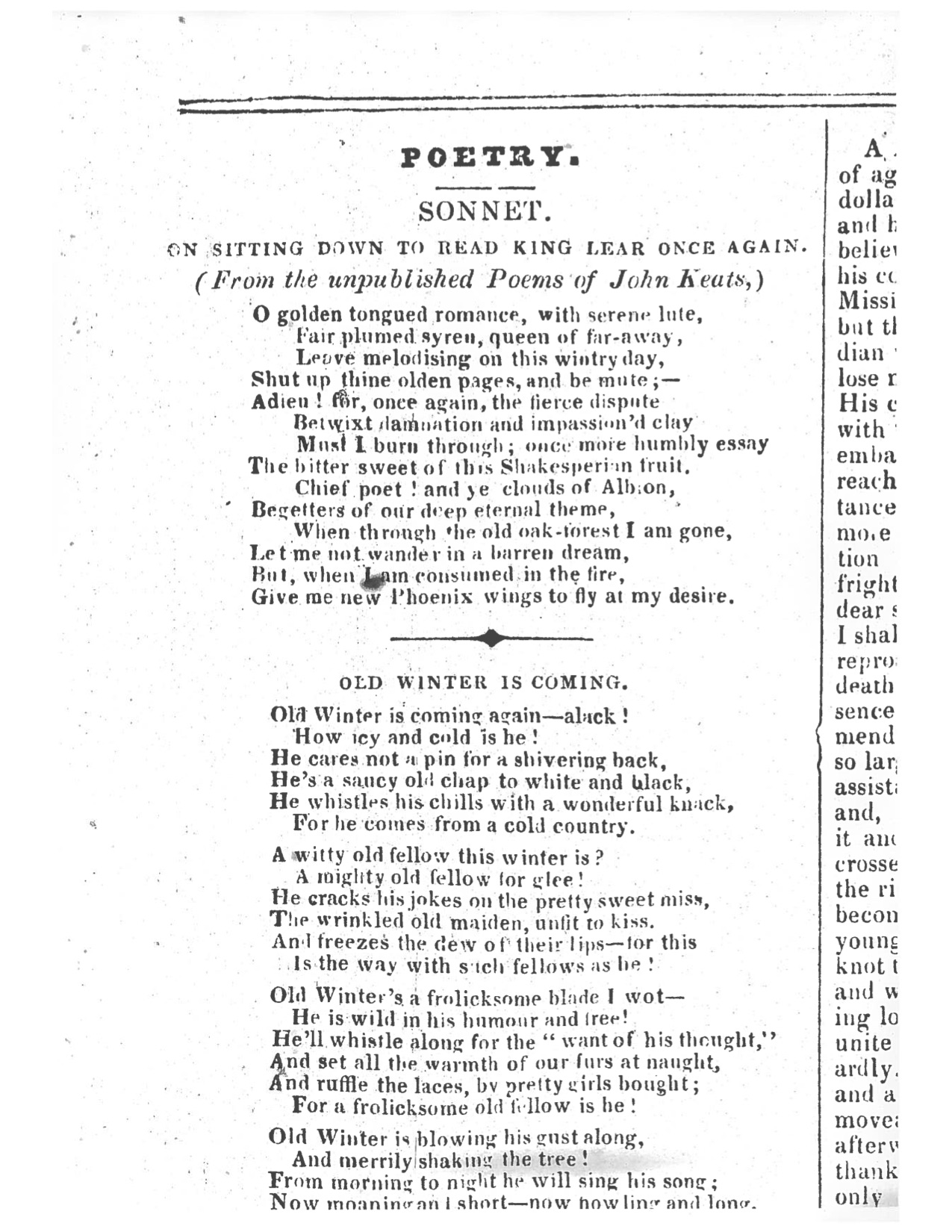

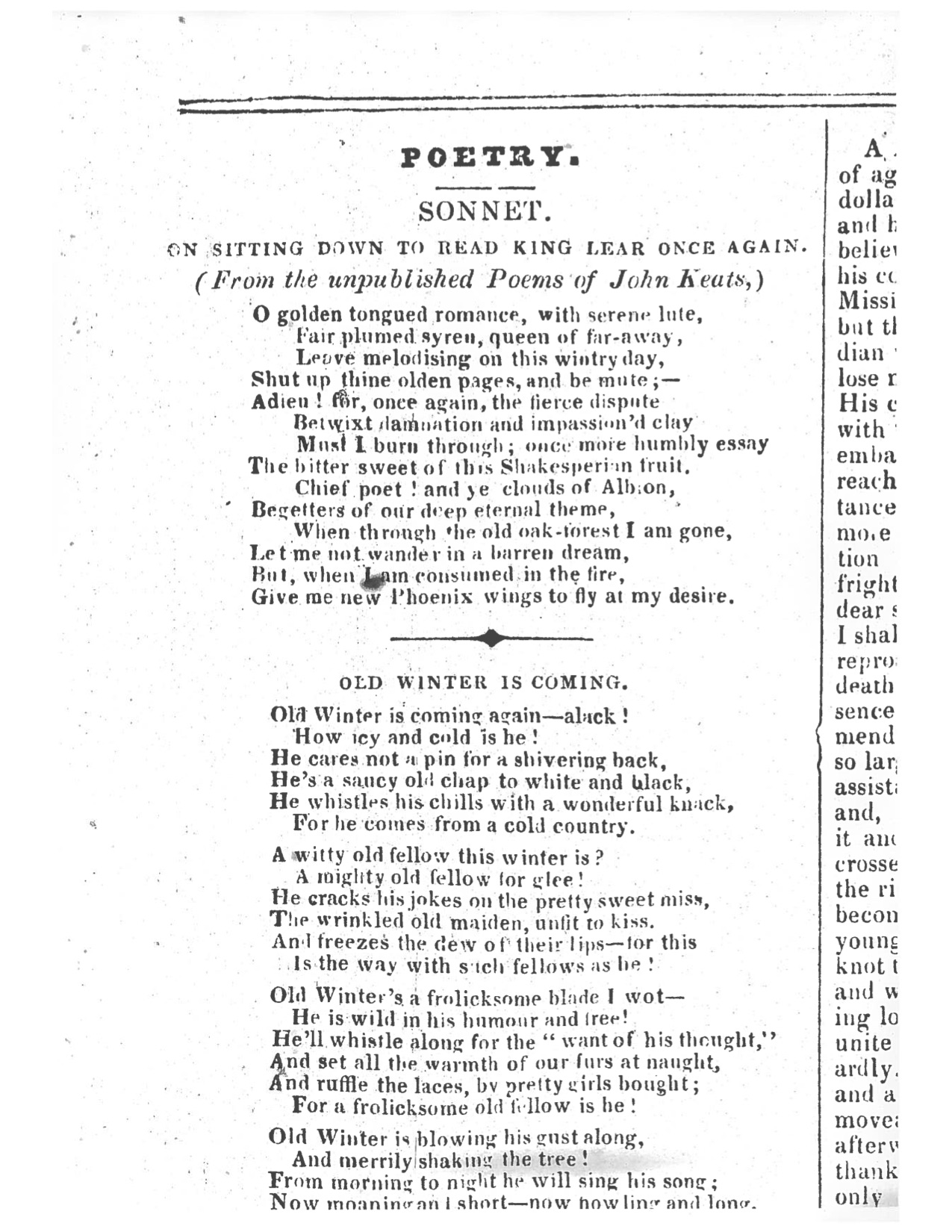

Keats has Shakespeare’s King Lear on his mind, and along with Hamlet, it remains for Keats the most potent poetic measure of depth and complexity. Today

Keats writes a sonnet about the play—Keats remains overwhelmed by the greatness of the thing

(23 Jan 1818, to Bailey).

In gauging his own progress, and with King Lear in mind, Keats

writes that there has been a little change […] in my intellect lately,

and that

Nothing is finer for the purposes of great productions, than a very gradual ripening

of

the intellectual powers

(letters, 23, 24 Jan). The suggestion, of course, is that Keats

is himself feeling or hopes to feel such a ripening,

and this (as a metaphor of organic

maturation) is important in his self-conception of poetic progress. His long

trial-of-invention poem, the 4,050-line Endymion, will, within two months,

finally be behind him. He has just shown the opening book of Endymion to Leigh Hunt, who sees himself as Keats’s mentor; and Hunt, in

skimming it, says it has not much merit,

and that the conversation between the two main

characters is unnatural & too high-flown.

Hunt also adds that they would not speak

like his own characters in his own poem, The Story of Rimini. Keats finds

Hunt’s comments wrong, not to mention both petty and pompous. More reason for Keats

to move

even further from Hunt’s sway of influence, though there is some truth in saying that

Huntian

tones do inhabit Keats’s rambling poem (and a fair amount of his early poetry).

Although Keats’s sonnet on King Lear is about both Shakespeare’s greatness as well as his own

aspirations for greatness, On Sitting Down to Read King

Lear Once Again itself is not especially great. Keats resorts to a

couple of clichéd, rhapsodic phrases—O golden-tongued Romance, with serene lute!

—on his

way to call upon The bitter-sweet of the Shakespearean fruit

to help his wings to

fly at my desire

—his desire

to be an enduring poet, that is. This is Keats’s most

persistent—and dead-end—topic, especially in its ties to poetic fame. But there is

at least

something more deliberate and important in the sonnet, something that expresses a

specific and

deliberate mandate for this poetic progress: to say good-bye to melodizing

romance

while welcoming the Shakespearean deep eternal theme

of sadness and pain, of

immortality and death. This welcoming is significant enough: beginning in his earliest

work,

Spenserian impulses especially run through Keats’s diction and poetic mannerisms;

but as he

matures, the charms of chivalric beauty and elfin ambiance increasingly limit his

more intense

and comprehensive goals, and after Endymion they begin to noticeably drop

off. The allegorical-mythical romance of Endymion holds up rather than advances

Keats’s progress—but at least he learns what he shouldn’t do again. As he suggests

in the

overly apologetic preface to his too-long poem, he pledges that if and when he returns

to a

Greek mythology, it will be with some poetic maturity.

At the end of January, Keats writes a kind of follow-up poem—When I have fears—to the Lear

sonnet. It may be his first Shakespearean sonnet. Keats fears that time will compromise

his

teeming brain

and poetic aspirations, and therefore it returns to Keats’s thus-far

longest running subject: the desire to be inspired and to write inspirational poetry,

and how

he might accomplish these goals. This time, however, the sonnet is personal yet less

affected.

Although the poem Byronically self-dramatizes his gloomy fears and status—I stand

alone

—it remains more controlled in attitude and purposefully dramatic in its rhetoric.

But what we are beginning to see more and more clearly is that Keats wants to, as

it were,

find some new beginning to his poetic pursuits. We might venture, then, that Keats

is working

toward a third phase of poetic development (the first revolving around his first collection,

the 1817 volume; the second revolving around the completion of Endymion); it will be his last, and will mark a leap forward in his prowess as a

poet. How strongly does Keats feel he has a new phase to move to? The next day, 23

January, in

a letter to his close friend Benjamin Robert

Haydon, Keats deliberately anticipates leaving behind the sentimental cast

of

Endymion so that he can move on to his Hyperion project,

which will be written in a more naked and Grecian manner

and be more undeviating

in its intention and narrative. In short, Keats is self-consciously is working toward

less

ineffectual poetic decorum, more direct story-telling, and a more elevated style.

This bodes

well.

Keats also likely writes another poem in January that somewhat similarly signals his

desire

to feel absorbed by the thoughts of earlier writers. The lively Lines on the Mermaid Tavern

once more expresses Keats’s desire for alignment with Souls of poets dead and gone.

The

mythology revolving around the Mermaid Tavern (where Keats spends at least one evening

around

this time) is that famous Elizabethan writers gathered there as a club to have drink,

converse, debate, and exhibit wit. Maybe something will rub off on him.

As suggested, King Lear, with its speculative, intensive depths, remains perhaps the most powerful single creative work for Keats. We know from Keats’s heavily marked up copy of William Hazlitt’s recently published Characters of Shakespeare’s Plays that he is fully absorbed with trying to understand King Lear’s imaginative portrayal of and control over tensions, passions, conflicts, and oppositions. This becomes Keats’s real work at this time, and, as he copies and revises Endymion, its shortcomings—indeed, its relative haphazard quality—become very clear. Keats recognizes that, to be a significant poet, he needs to embrace depths and complexities in feeling and thought, and in composed and disinterested yet imaginative ways; subjects are to be finely pushed up against excess without crossing over into sentimentality. Keats is coming to see that life, feelings, and thought are necessarily at the call of change, uncertainty, and irresolution; imaginatively embracing and representing this realization and these topics is critical, and something we might call Keats’s reality principle—and, once more, they will be present in his best work to come.

Likewise, and related to this pursuit, Keats about this time begins to realize that

he needs

to—and can—profitably engage with the achievement of Milton and Wordsworth, alongside

Shakespeare. For Keats, Milton’s verse

unshakeably holds its subjects, thus turning moving description into stilled drama.

Wordsworth’s verse pursues deep, quiet truths beyond both joy and fear—a region that

Wordsworth seminally points to as too deep for tears

(from Wordsworth’s Immortality Ode). Equally significant, Keats begins to know what he

will not emulate: aspects of Milton’s style and Wordsworth subjectively channeled

vision. Yet,

in about a year-and-a-half, just as Keats writes his very best poetry, he can say,

Shakespeare and the [Milton’s] Paradise Lost every day become greater wonders to me

(letters, 14 Aug 1819), and we witness Keats’s recognition of the importance of how

Wordsworth

can think into the human heart

(letters, 3 May 1818). We know, then, that Keats’s

deliberate study of these figures in particular profoundly propels his own work. [For

more on

Milton and Wordsworth, see 5 May 1818.]

That William Hazlitt is both a friend and a

critical influence is not coincidental: Keats at this juncture reads Hazlitt’s critical

work,

attends his lecture series on literature, and socializes with him. They no doubt talk

about

the qualities of poetic stature, which ties into Keats’s interest in how the actor

(and living

legend) Edmund Kean embodies Shakespeare’s words—a quality to which Hazlitt is greatly

attuned, and something he has written about. This shapes Keats’s idea about how poetic

voice

assimilates and represents meaning. Keats is intrigued by Kean’s ability to physically

evoke

Shakespeare’s actual words (his physical text, in effect): the character becomes the

words,

and words become the character. That is, Kean’s acting embodies words as much as persona.

This

anticipates Keats’s own theory of the camelion poet

(letters, 27 Oct 1818); Kean is, in

effect, the camelion actor, assuming, as it were, the changing shapes and colours

of

Shakespeare’s words. Keats’s ultimate ambition, expressed at the height of his powers,

is

to make as great a revolution in modern dramatic writing as Kean has done in acting

(letters, 14 Aug 1819); this never happens, though—who knows?—if Keats would have

lived beyond

twenty-five years, his remarkable poetic gifts may well have been translated into

drama.

At this moment, Keats is somewhat defensive about his poetry in light of Hunt’s somewhat patronizing comments about Endymion. The suggestion is perhaps not so much that he does not trust Hunt’s comments, but that Hunt makes them in the first place, which suggests Hunt’s sense of ownership over Keats’s poetic progress. There may be something that Keats might not want to directly admit: that aspects of Hunt’s poetic style (which is overly affected, at times, prettified, sometimes stylistically flippant) lurk in his own poetry. But, as suggested above, Keats knows this, and he is very determined to move forward in his own way and in his own terms, fortified by his study, his poetics, and the support of his closest friends.

The next day (23 January) Keats begins to prepare Book II of Endymion for the press, and his brother Tom’s health is not good. As usual, Keats’s finances are uneven at best and precarious at worst.