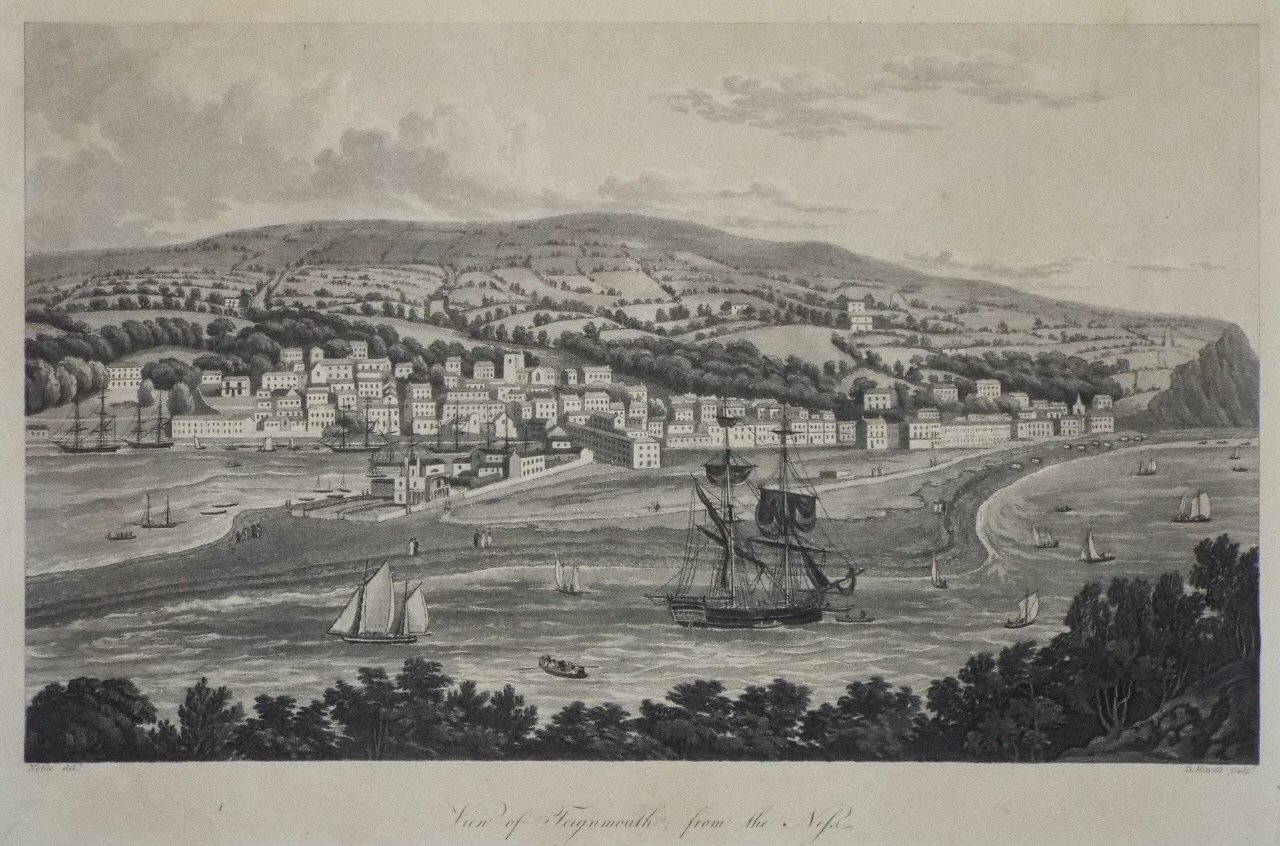

5 May 1818: Good-bye Teignmouth, Hello Mansion of Many Apartments

Teignmouth to Bridport

After just about two months in Teignmouth, Devon, Keats and his brother Tom are on their way back to Hampstead. The trip normally takes

little more than two days; it takes them about six horrible days. Tom is very ill

with

consumption; he’s hemorrhaging. On their return, they stay at Bridport so that Tom

can rest.

As Tom himself recalls a few weeks later, I was very ill there and lost much blood

(17/18 May). Tom improves by the end of the journey, so much so that a doctor, despite

obvious

indicators of consumption, tells Tom that his illness is all mistaken,

making Tom

almost giddy. Sadly, Tom, aged 18, does not make it to the end of the year, and he

dies with

Keats beside him.

Despite some very soggy weather, for Keats the stay in Teignmouth is mainly successful.

After

about a year of working on his long poem, Endymion, it is at last behind him and

published. Keats, however, remains fully ambivalent about its value, and he says so

well

before he even completes it: on one hand, his perseverance has been tested and proven

by a

poem that, at various times, he largely views as a trial or exploration of his imaginative

powers; on the other hand, the poem is overwhelmingly weak; Keats is aware that his

slapdash

idea for the poem (to make something big from something little) and his adolescent

imagination

are on display. As Keats writes about Endymion in his cringe-worthy preface to the poem,

its foundations are too sandy

— it displays great inexperience, immaturity, and every

error denoting a feverish attempt.

He’s right. But, importantly, he’s learned what kind

of poetry does not stretch his deeper capabilities.

Despite—or maybe because of—the undeveloped, dead-end nature of Endymion, Keats in fact returns from his trip with maturing, unique, and powerful

ideas about human life and poetry. In April he sounds a determination to pursue both

the

Principle of Beauty

and knowledge

with deliberate study and thought

(letters, 9, 24 April). Now, in May, Keats begins to describe what he believes are

the complex

qualities of the ripening poetic and philosophical mind, one that sees through and

beyond

bias, contradiction, and misery. Sensation and knowledge, heart and head, good and

evil: these

are neither exclusive nor binaries, and only by seeing and exploring beyond them with

single

vision can fears be truly put aside in the name of that Principle of Beauty.

Much of

this is worked out in an important letter of 3 May to his very good friend and fellow

writer,

John Hamilton Reynolds, as Keats critically

probes and gauges the relative poetic qualities and accomplishment of John Milton and William

Wordsworth—relative to his own aspirations and style of thinking and expression, of

course.

Keats needs some kind of model or (what he calls) simile to explain this, and he constructs

one: he compares human life to a large Mansion of Many Apartments.

He pictures chambers

of thoughtlessness and delight that delay us in our exploration, but awareness of

the world’s

misery and heartbreak, pain, sickness, and oppression

darken these chambers to a

vision beyond good and evil. The furthest we can go (or have gone) in the Mansion

are to

dark passages,

to a Mist

—to Wordsworth’s burden of a Mystery

(as named in Wordsworth’s Tintern Abbey, line 38). Keats believes that Wordsworth’s

Genius

is to have seen as far as possible into the human heart.

For this

reason, Keats suggests that Wordsworth’s vision is deeper

than Milton’s.

With this fairly intense and important reasoning, Keats extends his idea that doubt

and

mystery are strengths in thinking, being, and feeling; they are to be explored. Sorrow is

Wisdom,

he writes; for aught we can know for certainty!

All of this will, within

a year, propel Keats’s poetry as he moves toward his one and only year of great composition,

1819. How does a capable imagination represent life’s dark, sorrowful reality? How

can this

acceptance be voiced—and creatively projected upon what? The poetry he writes will

reveal that

he can look upon and represent subjects—big subjects, complex subjects, inconclusive

subjects—with contained intensity, and without excess of either thought or feeling;

and,

perhaps most importantly, in an unforced, non-distracting style. In short, he finds

a mature

voice and poetic forms that allow exploration of a subject through its own nature

or

qualities, even if these natures and qualities might ultimately be unknowable. It

might be the

silent form of an indecipherable, antique urn; or the woeful, confused experience

of a knight

with an incomprehensible belle dame; or an encounter with a nightingale that evokes

thoughts

too deep for consciousness and mortality.

But back to the pedestrian realm: the next few weeks after arriving back in Hampstead, Keats frantically catches up with most of his London friends, numbering about a dozen, including the painter Benjamin Robert Haydon, William Hazlitt (the important critic and influence on Keats’s poetics), John Taylor (his publisher), and Reynolds (friend, critic, poet). These occasions are sometimes full of silliness, such as an all-nighter with Haydon and friends on 11 May, when the party members, likely fuelled by some drink, pretend to be various musical instruments (apparently Keats is the bassoon).

In the air are his brother’s—George’s—marriage (28 May) and George’s plans to emigrate to America, as well as Keats’s plans for a tour of Scotland and northern England. Keats will not look forward to the rough treatment he gets from certain conservative reviewing quarters. His friend Benjamin Bailey, however, will write a very favorable review of Endymion at the end of the month, for which Keats thanks him (10 June). It’s nice to have friends, and Keats’s supporters number more than a few. Something to keep in mind: Keats by this time has, as a poet, done little to earn any claim to even minor significance, yet the range and experience of the friends he attracts after falling in with Leigh Hunt in October 1816 is quite remarkable, and it surely says something about Keats’s personality, his intelligence, and his perceived capabilities as a great poet.