5 January 1818: Charles Wells & the Not-to-be Interrupted Wordsworth

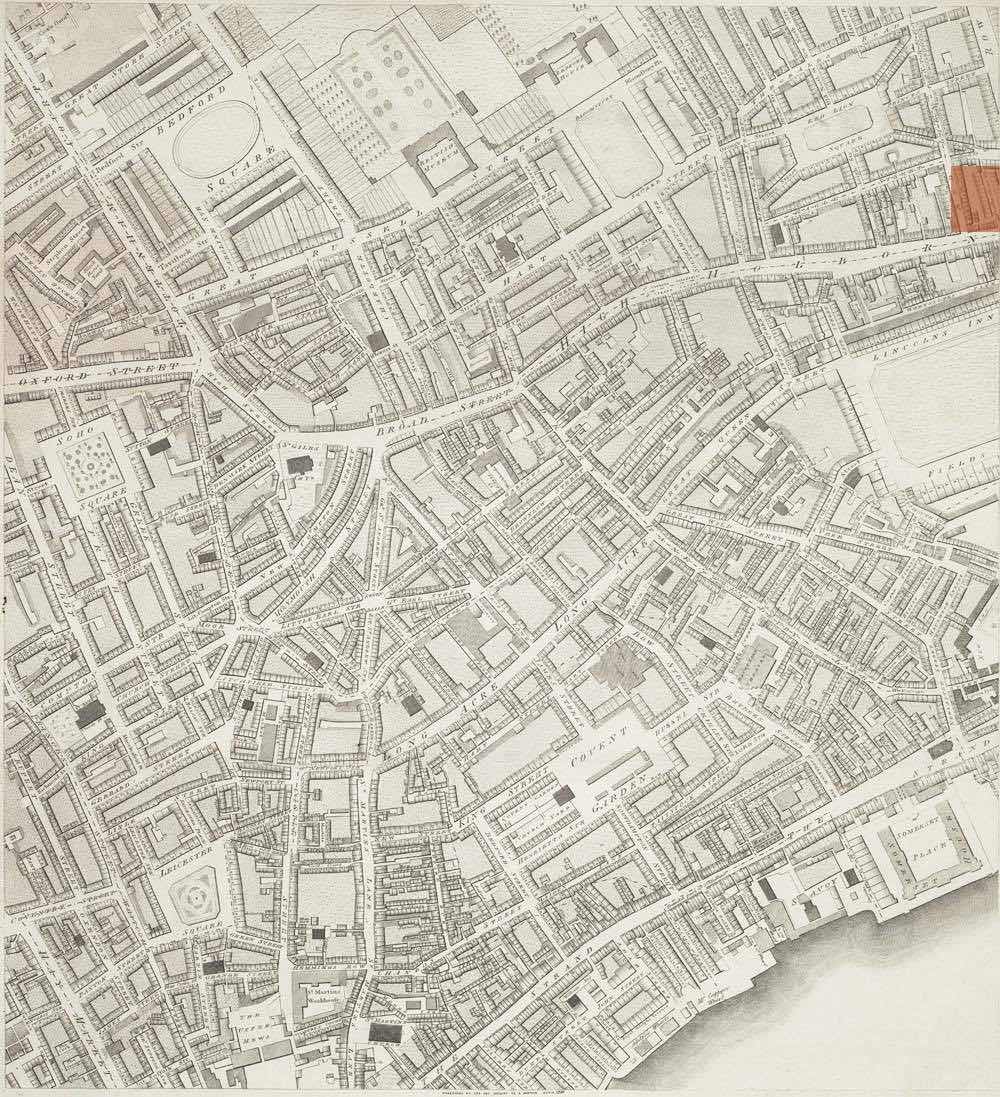

Featherstone Buildings, London

On this day during a very busy month of socializing, Keats sees Charles Wells, a minor poet, and friend of Keats’s via Keats’s younger brother, Tom. Wells and Tom were school-fellows in Enfield at Clarke’s academy, which Keats also attends, 1803-1811.

Back in June 1816, Keats writes an indifferent occasional poem to Wells, To a Friend Who Sent Me

Some Roses, brought on by a minor dispute between the two, and published in

Keats’s first collection, the 1817 Poems, by John Keats.

Phrases from the poem—like lush clover covert

and feasted on its fragrancy

—place

it squarely in Keats’s earliest period of mainly ineffectual poetry, where overly-styled,

fluffy poeticisms too often compromise a determined poetic purpose. Now, in early

1818, Keats

looks forward to deeper, more probing subjects in his poetry-to-come.

Keats also sees a surgeon, Solomon Sawrey, on this day. He is very concerned about

Tom’s blood-spitting, and his concerns are shared

with both Tom and his other younger brother, George. No doubt it is consumption. As a young teen, Keats witnesses his mother pass away from this horrible

wasting

illness, so he knows something about how things could play out. Keats’s

medical training and experience also certainly darkens his hopes. Keats is deeply

connected to

his two younger brothers.

Despite some bad weather, in the evening Keats dines with William Wordsworth as well as with Wordsworth’s wife, Mary; his sister-in-law, Sarah Hutchinson; and Thomas Monkhouse, who is a cousin of Mary and Sarah. At the moment, Keats seems too

distracted to get on with revising and correcting his long poem Endymion for publication, though he plans

to have the first of its four books done and ready for his publishers by the middle

of the

month. Keats has some second thoughts about actually publishing Endymion, despite the huge amount of time he has spent on the poem—a great deal of

1817, in fact. Borrowing Keats’s own words from the uncomfortable Preface he eventually

publishes with the poem, one part of the rapidly maturing Keats thought it might have

been

better to just let it die away

(p.viii). Completing the poem may have proven Keats’s

dedication to poetry; it does not, however, prove he is a great poet—and he knows

it.

Keats sees Wordsworth a fair amount around

this time (while Wordsworth is visiting London), though not all that much of what

takes place

in their meetings is known. But it might be a safe bet to assume they talked about

poetry,

with Wordsworth no doubt holding court, as it were. After all, Wordsworth’s status

and

experience as a poet (Wordsworth’s almost thirty years as opposed to Keats’s three)

completely

trumps Keats’s. There will be a growing sense, then, that Wordsworth, so highly influential

for Keats’s development of serious, deep poetry, is also beginning to seem like a

protected,

conservative fuddy-duddy and a bit of an egoist; some of Keats’s London crowd begin

to express

as much, and it also works into some contemporary criticism of Wordsworth’s poetry.

Obvious,

too, is that Wordsworth’s political sympathies seemed to have taken the opposite direction

to

Keats and more or less all of Keats’s friends, who are often on the liberal and reformist

side

of the question. But again, Keats nevertheless must have felt privileged to have contact

with

the greatest poet of the age, and, again, it is difficult to imagine exchanges between

Wordsworth and Keats—was there question and answer? pontification? poetical gossip?

name-dropping? poetry recitation? encouragement or advice for the young poet? Apparently,

as

Keats found out from Wordsworth’s wife, Mr. Wordsworth was not to be interrupted when

speaking. A number of weeks later Keats expresses his mixed response about Wordsworth’s

stay

in London and his own mixed regard for the older poet: I am sorry that Wordsworth has left

a bad impression wherever he visited in Town—by his egotism, Vanity and bigotry—yet

he is a

great poet if not a Philosopher

(letters, 21 Feb 1818). This really says it all.

There is nothing, however, that gives evidence of Wordsworth having a high regard for or even much interest in Keats, even though he outlived Keats by almost thirty years, and no doubt he witnessed Keats’s rapidly growing reputation into the Victorian era. Keats had sent a copy of his first volume of poems to Wordsworth with a reverential inscription to the older poet, but it appears that only a few of the leaves of the book were ever cut.

Keats at this time now gains both determination and confidence in taking his own poetic

direction relative to Wordsworth, one that

privileges a wide vision determined by the subject itself and with an empathetic imagination,

and not obscured or contaminated

(letters, 3 Feb 1818) by an inward or inconsequential

purview. But Wordsworth’s poetic exploration of the meaning of human suffering and

loss in the

context of nature’s beauty and permanent forms remains for Keats a measure of—a model

for?—his

progress. Keats’s crucial critical question: How can he go as deep as Wordsworth in

a way

unlike Wordsworth?