27 January 1818: Hazlitt’s on the English Poets & Wordsworth’s Subjectivity; the Poems of January 1818

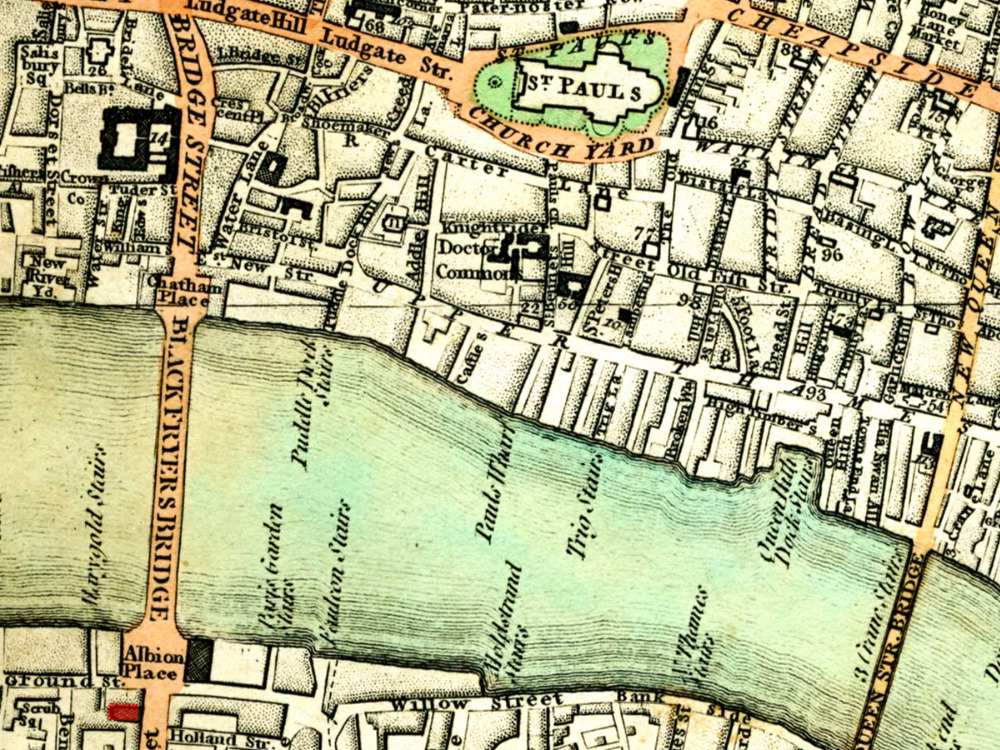

Surrey Institution, Blackfriars Road, London

William Hazlitt gives three lectures on English poets at the Surrey Institution during January, with more continuing into February and early March. Keats almost certainly attends the third in this series on 27 January, as well as another on 3 February. Keats, we know, has great respect for Hazlitt’s critical tastes, dating from at least mid-1817.

After condemning poets of the modern school of poetry

for excessively expressing a

morbid feeling and devouring egotism,

Hazlitt notes that Shakespeare and Milton

owe their power over the human mind to their having had a deeper sense than others

of what

was grand in the objects of nature, or affecting in the events of human life.

This

begins to resonate hugely with Keats, who, in his poetic development, now attempts

to go

beyond romance and lighter, pleasurable, and occasional topics and work toward subjects

of

a deeper sense

—objects of nature

and events of human life.

Keats is also aware of Hazlitt’s comments about Wordsworth’s style of poetry, that, according to Hazlitt, Wordsworth’s intense

intellectual egotism swallows up every thing

(first expressed by Hazlitt in The Examiner in 1814). In the 1817 Round

Table discussion of Wordsworth (gathered essays from The

Examiner), Hazlitt notes that Wordsworth sees all things in himself [. . .] He

only sympathizes with those forms of feeling which mingle at once with his own identity

[. .

.] The power of his mind preys upon itself. It is as if there were nothing, but himself

and

the universe.

Hazlitt notes that no matter what speaker or narrator Wordsworth employs,

they are the same character: Wordsworth. [H]is thoughts are his real subject,

writes

Hazlitt. But, Hazlitt notes, Wordsworth is also a deeply contemplative and philosophical

poet,

and, with subtlety and profundity, he describes the love of nature better than any

other

poet.

Throughout 1818, and almost certainly following Hazlitt’s complicating views on Wordsworth, Keats is keen to distinguish his own poetical Character

from

the wordsworthian or egotistical sublime

and the whims of an egotist,

which

leads to poetry that has a palpable design upon us

(27 Oct 1818 and 3 Feb 1818). This

determined self-differentiation from Wordsworth (whom Keats met a number of times

fairly

recently) is crucial for Keats in developing his own style of reflection and expression,

inasmuch as it also means he desires to comprehend Wordsworth’s weighty achievement,

which

Keats finds to be considerable and pivotal in his own direction. More specifically,

Keats

realizes that for his poetry to progress, he needs to go as deep as, or at least engage,

Wordsworth’s ideas about the connection between joy and suffering—expressed in Wordsworth’s

dominating trope of the human heart. And over the next few months (and reflected in

a critical

letter of 3 May to John Hamilton Reynolds),

Keats is determined to understand if Wordsworth’s explorative

genius is limited or

grand in its scope. Practical questions for Keats might be: How do I go as deep as

Wordsworth in a style that is not Wordsworthian?

How do I write poetry with poetic purpose that does not draw attention to that purpose,

but only an overriding sense of Beauty? How do I become the unpoetical poet?

Besides January 1818 being an extremely socially active month, Keats manages to write at least eight poems, though one is left unfinished. Three are incidental and mainly trivial: he has some naughty fun with a dirty little ditty that harks back to an older, bawdy tradition—O blush not so!; he sentimentally celebrates a friend’s mother’s old, beat-up cat in To Mrs. Reynold’s cat; and he advertises his fondness for drinking in Hence burgundy, claret and port).

More is at stake in three of those other January 1818 poems. In them, Keats returns

to his

longest-running topic, one that, paradoxically, both motivates him and holds him back:

articulating his desire and aspirations to be an enduring poet. These poems do, though,

sound

some minor progress in his writing. In particular, his style and voice do not distract

so much

from his sense of subject and purpose. Keats is set off—fevered and flushed—by seeing

what he

believes is a bit of John Milton’s hair that

Leigh Hunt shows him: Lines on Seeing a Lock of Milton’s

Hair praises and, in a way, even worships Milton’s powerful, perdurable poetry;

it is, Keats notes, a poetry that operates beyond time and place and fashion; and

this is

sing3ularly important for Keats, who, as he writes, hopes that with years of work

his voice

might also carry of such lasting depths and powers. Keats, we see, with his ambition

and

self-belief, already has in mind an after time

for his hoped-for better work-to-come.

In On Sitting

Down to Read King Lear Again, Keats marks his

humility in the presence of Shakespeare’s deep, dark tragedy. (We might also note

that Milton

and Shakespeare in these two respective poems are both declared the Chief

of all

writers; Keats, it seems, at this point cannot chose between what she hope are his

great

precursors.) A third poem—When I have fears that I may cease to

be—is also serious and direct in expressing his poetic aspirations. Most of the

sonnet crosses over into his fears that he might not live long enough to express all

that he

might feel or see, and that (striking a kind of Byronic pose of standing alone) fame

might

fade before his time comes. There is, also, a last poem of the month, God of the meridian, a kind of

experiment that seems to ramble toward the idea that, somehow, the God of Song

might do

something to temper or position his poetic feelings; but that is about all; the poem

struggles

just to physically place the speaker. Behind all of these poems, Keats recognizes

that he will

need to develop his poetic skills to keep pace with his penetrative poetics.

Keats also expresses unease with his long poem, Endymion, which is in early stages of

going to press: I am convinced now that my Poem will not sell.

He’s right. But this

realization is a good thing, since, in the process of preparing his poem for publication,

he

comes to critically assess its significant shortcomings—a random, stretched plot;

too much

aimless description; an overly dainty tone (especially in the dangling, jingling couplets,

where the arbitrary connections of sounds determines sense, rather than supporting

it) that

does not always fuse with the poem’s more sensual moments; and a thematics (variations

on the

ideal/real binary) that hardly displays much originality.

Endymion’s

shortcomings and prospects makes Keats sound an ultimatum: he writes that he will

give his

career as a poet three more months. After that, he will seek other employment (Home or

abroad

) or find a cheap way to retire

in the country. But this is momentary

bluster, brought on by both financial pressures and relatively little poetic progress

and

success. Pressures and dissatisfaction, however, do not stop his lingering aspirations;

and,

for the better, Endymion serves to remind Keats of the kind of

poetry he will, hereafter, not write. What he is brewing is an epic poem based on the

Greek Hyperion story (the conflict between the Titans and the Olympians), and Keats

plans to

write his poem in a more direct, elevated style that, in part, and at least initially,

owes

something to Milton’s influence. Hyperion will be (and in fact becomes, in two impressive but

incomplete incarnations) the anti-Endymion. But Keats is eventually stymied

by either his inability to fashion an engaging, continuous narrative, or the feeling

that

tonally and stylistically the poem does not represent his own poetic voice. As we

will see,

the lyrical impulse in Keats needs to be met on his own terms—his own critical and

imaginatively capable terms—and not on the accomplishments or style of his precursor

poets.

The end of January shows Keats having, as usual, financial issues. He has received

more

tricklings of money from the trustee (Richard

Abbey) of his inherited and apparently dwindling family funds, but as he writes his

brothers in a letter postmarked 30 January, money he owes to friends nearly swallowed up

the Balance.