16 January 1818: Dinner with Reynolds & the Goals of Keats’s Progress

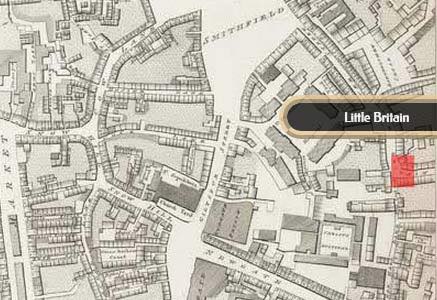

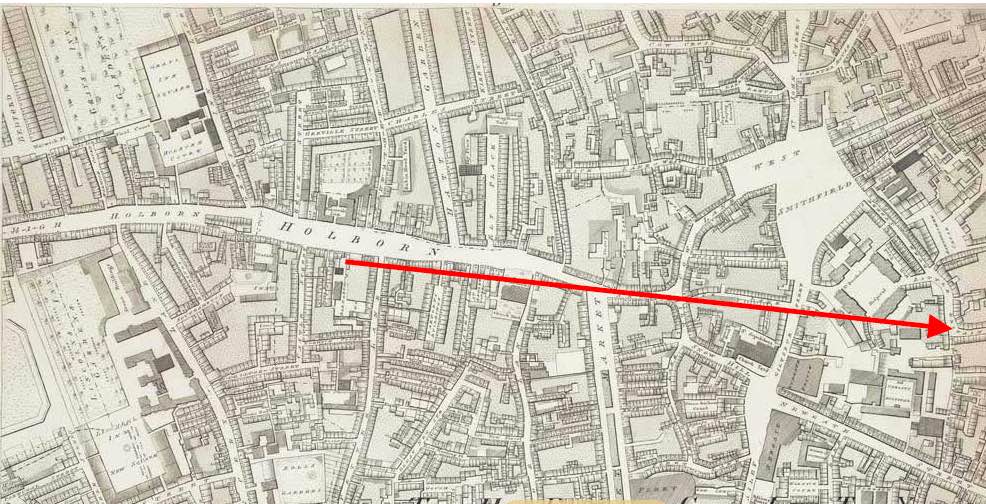

Little Britain (street), adjacent to Christ’s Hospital, London

John Hamilton Reynolds is about a year older

than Keats, but he has already had some significant literary experience. Perhaps because

his

talents are largely derivative (in particular, of William Wordsworth, Lord Byron, Leigh Hunt, and Walter Scott), in 1818 he mainly gives up his literary career for a so-so career in

the law, though he continues to dabble: he wittily writes, As time increases, / I give up

drawling verse for drawing leases.

Perhaps his literary highpoint as a poet comes in

April 1819, when he cannot help but offer a very funny and ingenious parody of William

Wordsworth’s

Peter Bell, A Tale in Verse, entitled Peter Bell, A Lyrical Ballad, and published under two weeks before Wordsworth

actually publishes his own poem (Reynolds’ satire actually reveals how utterly familiar

he is

with Wordsworth’s writing). Reynolds’ father is a writing and math master at Christ’s

Hospital

school. Previously, the Reynolds family reside at 19 Lamb’s Conduit Street.

Keats meets Reynolds through Leigh Hunt mid-October 1816. Reynolds in turn introduces Keats to Taylor & Hessey, who become Keats’s publisher, and assume right over Keats’s first 1817 collection (which had been published on commission). Among others, but importantly, Reynolds also introduces Keats to Charles Wentworth Dilke, Benjamin Bailey (who becomes a good friend and literary influence), and Charles Brown (who also becomes an extremely close friend, travelling companion, collaborator in writing a drama, and a financial supporter in Keats’s time of need).

Keats writes a sonnet based on a visit to the Reynolds’ 16 January, entitled To Mrs. Reynolds’ Cat—Mrs.

Reynolds

being Reynolds’ mother, with whom Keats has, at this time, a very friendly

relationship. Reynolds also has four sisters, and Keats greatly enjoys them; later,

though,

this changes when they seem to collectively disparage someone Keats likes, and then

later,

loves: Fanny Brawne. The sonnet, which actually

addresses the cat—who hast past thy grand climacteric

—appears light and playful, and

seems to have been composed to fulfill a whim rather than to mark a significant, insightful

occasion. Yet, within its witty tone, we encounter a genuine hint of mastery in Keats’s

ability to profitably enter the subject—in this case, empathetic entry into history

of this

old, embattled cat. The cat is not exactly the perfected form of, say, a Greek urn,

but Keats

is clearly intriqued with the soft, lasting beauty and the unknowable truths in the

various

hidden lives of Mrs Reynolds’ cat.

Reynolds remains a very strong supporter (both publicly and privately) of Keats’s poetry and abilities, perhaps most strongly after Keats’s death. The two poets share literary tastes (especially Shakespeare), and Reynolds also plays a part in weaning Keats from Hunt’s influence, as does another close friend at the time, the painter Benjamin Robert Haydon.

This is a very social period in Keats’s life, but not for the first time is Keats

both vaguely amused and put off by petty quarrels between some of his friends, ranging

from broken social engagements, touchy and inconsistent personality traits, and unreturned

silverware. He begins to write a number of shorter occasional

poems, and not always on important topics, and not always that good. Revisions and

corrections to his long poem Endymion are slow-going, and no doubt he needs distraction.

Toward February, Keats will begin to move relatively quickly toward genuine poetic

independence and maturity, though signs appear first in his poetics in letters to

his closest

family and friends. At the same time, making revisions and corrections to Endymion forces a necessary and important re-assessment of the

poem’s limited achievement and his own poetic goals; these insights inform in his

greatest

work to come. One of these is that art should not overreach, especially, and paradoxically,

when it reaches for deeper knowledge that explores and represents subjects like sorrow,

joy,

love, and mortality—which takes us to what Keats suggests may be the most important

part in

Endymion (there are very few): the Pleasure

Thermometer

passage, as he calls it in a 30 January letter to John Taylor. Keats adds some lines to this part of his poem (Book

1, 777-181). Here we have the idea that the Imagination can be seen as the means to

take him

to a Truth.

The short passage is indeed compelling, appearing, as it does, among the

other 4,000 or so lines of a poem that, for the most part, moves uneasily between

drowsy,

overwrought, and arbitrary sentiments, and an equally drowsy and random plot—not so

mention

some slack, bumpy, and cutesy rhyming. The passage, despite its complex and somewhat

confusing

logic of gradations working toward some sense of fulfillment, steadies Keats’s idea

that Truth

and Beauty, even within the human realm of a quest for happiness, are not exclusive,

that they

necessarily interpenetrate and complete each other. In this way—in a way we can now

call

Keatsian—the Imagination is a kind of spiritual faculty that places us in both the

mortal and

immortal realm, in both the flesh and in the soul, in the human realm and the natural

realm.

To poetically represent these tensions in a composed, undogmatic manner is the goal,

and the

result will mark Keats’s progress and characterize some of his best work.