January 1818: The Mermaid Tavern; Eagles rather than Owls; Toward Vastness & the Unobtrusive Subject

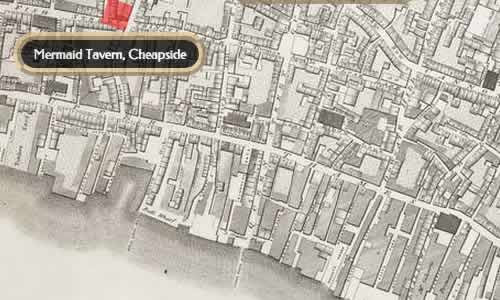

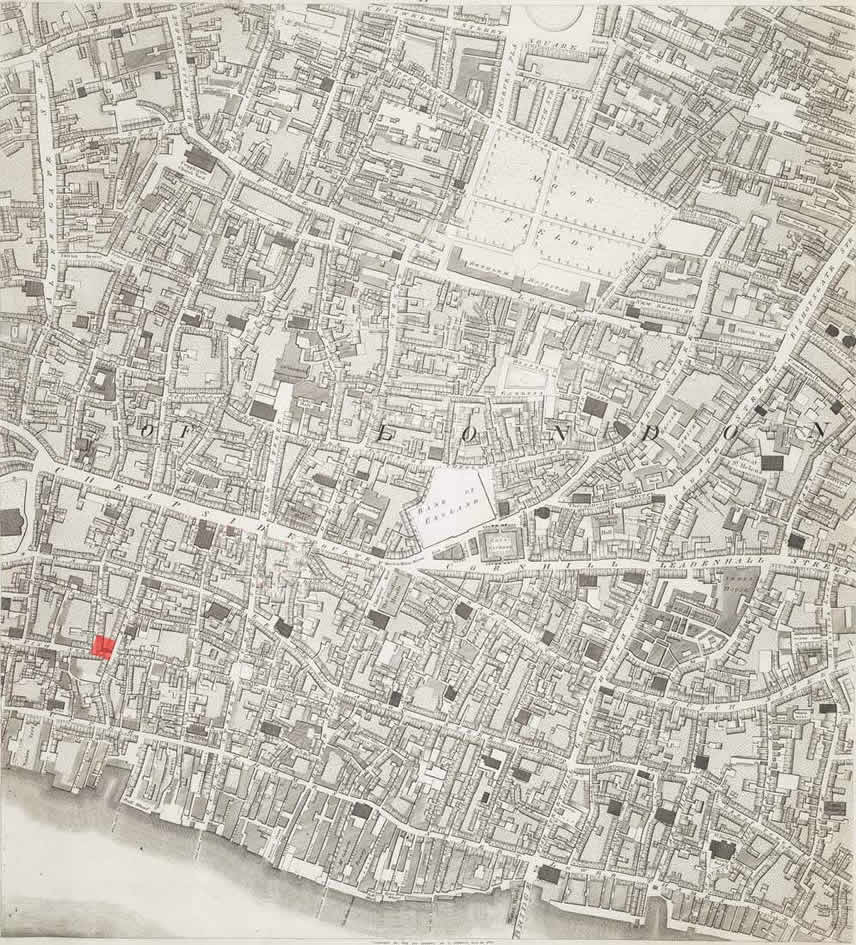

Mermaid Tavern, Cheapside, London

Where Keats, aged 22, has a drink sometime toward the end of January. At this time,

in a kind

of dialogical exchange of poems with his very good friend and fellow poet John Hamilton Reynolds, Keats writes an occasional poem about

the legendary Mermaid Tavern, noting that famous poets dead and gone

(like Beaumont, Jonson, Fletcher, and perhaps Shakespeare) also imbibed there, meeting as a

kind of drinking club (known as The Friday Street Club or Mermaid Club). The original

tavern

is destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666, and probably had entrances on both Friday

and Bread

streets. Keats may have spent the evening with two Horaces—Smith and Twiss—though an account of the night is unclear.* January

1818 is one of Keats’s most social months, and he sees most of his closest friends

and

associates during the month. Early 1818 can also be seen as a time when Keats’s thinking

about

the kind of poetry he wants to write (and the kind of poet he hopes to become) gathers

some

momentum.

As in much of his earlier poetry, Keats seeks association with or reference to other famous poets of the past, though this poem—Lines on the Mermaid Tavern—is not so striving or pandering as some of his earlier work, in poetry that constantly, and sometimes embarrassingly, desires association with great poets in the hope of becoming one: maybe something will rub off if he simply invokes them enough. That is, Keats’s early poetry often features a sense of hanging readiness. Fortunately, this later poem, while expressing some nostalgia, at least points to what kind of poetry he favors—as well as the community politics of free-thinking and Englishness, which Keats feels has been lost. In this way, the poem contains a kind of sideways political comment about his own times.

Shortly after composing Lines on the Mermaid Tavern, Keats repeats this lament of the loss of old times and old values more forcefully in another poem, Robin Hood. The poem signals what he sees as the repressive and materialistic nature of his own era relative to the spirit of Robin Hood’s time. The poem, with a little romantic propping, doubts that those olden times and values of true brotherhood and equality can be revived. Nonetheless, Keats’s two poems raise a crucial question: If the spirit of those old times is irretrievable, what kind of poetry will he, Keats, on his own, outside of any living brotherhood, be able to write? Keats will think this through in 1818. That Keats decides to publish both of the poems in his final and remarkable 1820 volume suggests they carry some importance for him; Robin Hood is perhaps the most openly political poem in the volume.

The Mermaid Tavern poem, though possessing modest poetic merit (remembering that Keats

writes

it in the more informal context of a dialogue with Reynolds), nonetheless has some interest that spins off from the kind of loss

described above. It subtly directs us to what Keats begins to reject in poetry and

what he

aims to embrace—and emulate: poetry that expresses or represents unobtrusive beauty

without an

ostensible, petty, or overbearing message. Keats, obviously self-directing his comments,

outlines the need for poetry that carries an ego-less voice and expresses itself in

a natural

style—unaffected, uncontaminated,

and immersed unobtrusively within the subject.

Unself-proclaiming poetry, we might call it. Again, toward the end of 1818 and into

1819,

these characteristics begin to appear in his poetry—balanced and confident—and these

will

constitute the period of his most remarkable poetry. From within his time, he will

attempt to

write poetry outside of his time. The brotherhood that Keats will try to join will

be via the

conversation his greatest poetry makes with other like-minded artists—then, now, and

in the

future.

To Reynolds on 3 February, Keats musters a

declarative tone. He condemns poetry that has a palpable design upon us.

Poetry,

he argues, should be great & unobtrusive, a thing which enters into

one’s soul, and does not startle it or amaze it with itself but with its subject.—How

beautiful are the retired flowers! how they would lose their beauty were they to throng

into

the highway crying out, ’admire me I am a violet! dote upon me I am a primrose!’

Keats

writes that he favors the Elizabethan poets over the modern poets; and, strongly sounding

his

independent direction, he writes that he will have no more of Wordsworth or Hunt in

particular.

Our desire should, he writes, be for the old Poets, & Robin Hood,

poetry that is uncontaminated & unobtrusive.

(This is his second use of the word

unobtrusive.

) He then quotes from his Mermaid Tavern poem.**

The 3 February letter to Reynolds does, then,

importantly mark out the direction for and nature of Keats’s progress. He does not

want to

write poetry that governs a mere petty state

; he desires a vast

dominion that

his poetry can overlook: Why should we be owls, when we could be eagles?

The analogy of

a narrow, unmoving, and perhaps huddled perspective—in the dark, no less— vs. a clear,

wide

perspective, suggests an expansion of what Keats wants to survey, or see,

in his

poetry; he wants to fly above the scene and see beyond small-mindedness. He does not

want to

compose affected and self-regarding poetry. Remarkably, the scope of his poetry-to-come

in

fact puts his poetic goals and axioms into practice. Keats’s poetic striving will

thus

minister the universal, rather than the particular.

Keats signs off the 3 February letter to Reynolds as his Coscribbler,

which is fitting since Reynolds is publicly

associated with Keats by Leigh Hunt on 1 December

1816 in The Examiner. Hunt also includes Percy Shelley as a young poet who will thoughtfully return the

scene of poetry to a genuine love of nature. Reynolds (about a year older than Keats)

had also

reviewed Keats’s first volume of poetry in March 1817 in The

Champion, and they see much of each other during this period. No doubt they spend

much time discussing poetry.

*Twiss is a minor wit, dramatist, raconteur, writer, and, in 1820, elected member of parliament for Wootton Bassett; Smith is a poet, stockbroker, and, later, novelist—and part of the Hunt-Shelley circle.

**Keats transcribes the mermaid poem a number of times, including in a letter of 30

January to his brothers, in which, via Smith’s account of an evening with Twiss, some

fun is poked at Twiss for spouting

extempore verses when in fact he had written them earlier. Keats notes that a couple

of his friends are impressed with his poem, including Reynolds.