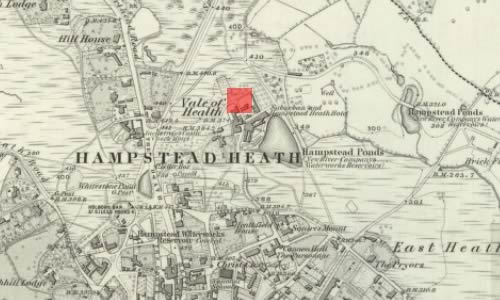

21 January 1818: Milton’s Hair, Milton’s Immensity, Bickering Friends, Hunt’s Diminishing Influence, & Leaving Childish Rhymes Behind

Leigh Hunt’s Cottage, Hampstead

Keats, aged 22, sees his friend and early mentor, the poet, publisher, and journalist

Leigh Hunt. Keats writes to his friend Benjamin Bailey (who is studying for holy orders at

Oxford) that Hunt has a real authenticated Lock of Milton’s Hair,

and that Hunt has decided that, on this day, he and Keats

should write poems about it.* Keats writes to Bailey that he might have done something

better alone and at home

(23 Jan 1818). Behind this comment may be the fact that Hunt

has just let Keats know that he feels Book I of Keats’s Endymion

has not much merit as a whole

(letters, 23/24 Jan). Keats believes that Hunt’s rather

high-handed comment is the result of Hunt feeling snubbed by not being thoroughly

consulted in

the composition of Endymion. Hunt may have felt some sense of

ownership over Keats’s poetic direction, since he was the first to publish and promote

Keats

(starting in autumn 1816), and early on Keats was indeed in awe of Hunt’s reputation

and

connections. But by early 1818, Keats is, as it were, increasingly his own man—and

poet. And

while Hunt will always remain a friend, he no longer remains Keats’s poetic preceptor.

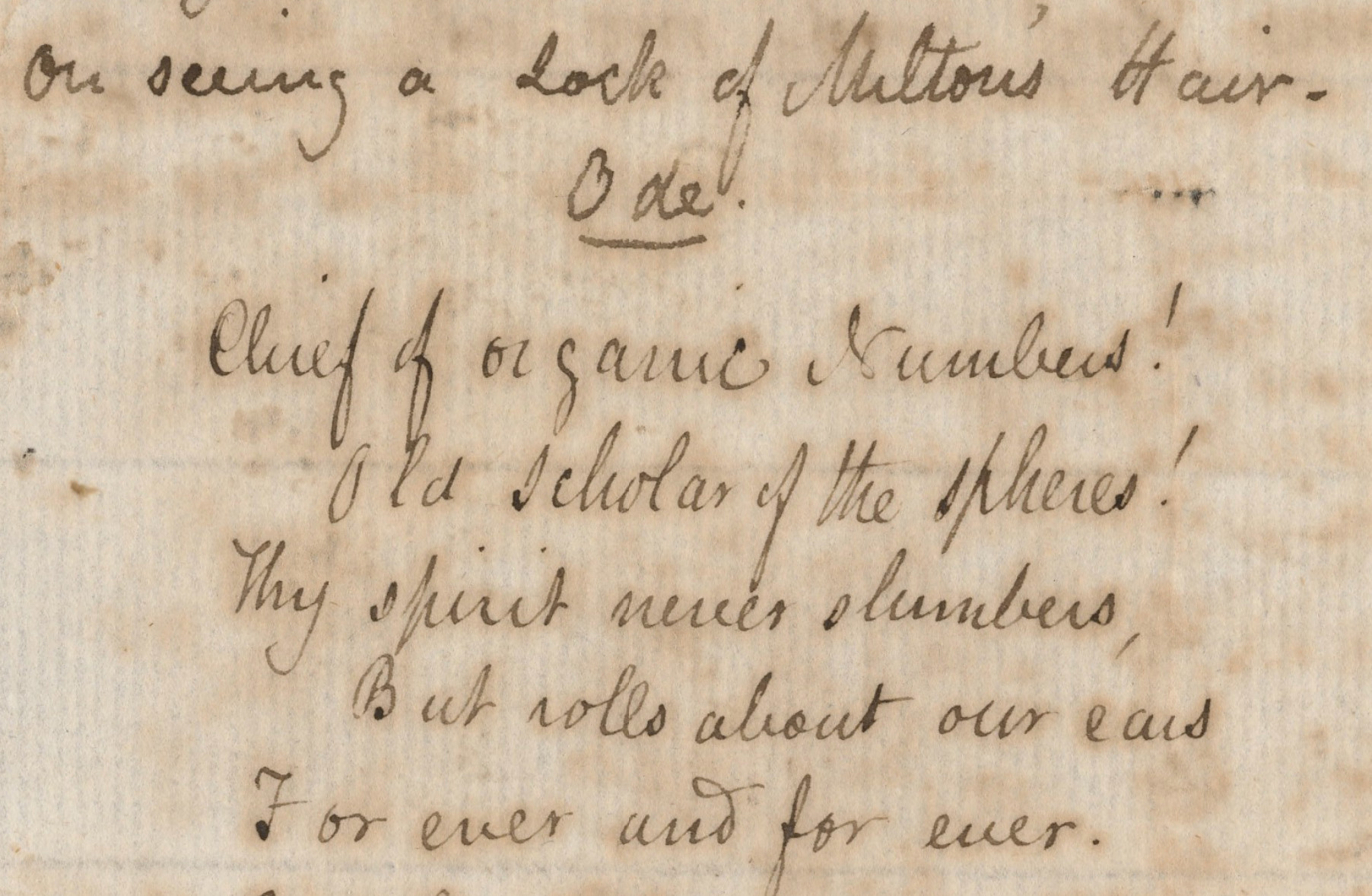

Nevertheless, with some enthusiasm, Keats’s to-order ode on Milton pictures a young mortal poet (himself, of course) with his

ineffectual rhyme standing in awe before the never-slumbering, immortal powers of

Milton. How

critically engaged is Keats with Milton’s poetic character? Just around this time

(or maybe a

few months later), we find Keats’s reading Milton’s Paradise Lost deeply and

critically. Keats’s extensive marginalia show that he is fully struck by Milton’s

genius—his

immensity and vastness, the magnitude of his conceptions,

his grand Perspective

alongside a Grandeur of Tenderness

; there are, Keats notes, completely

unexampled

and exclusive

moments even beyond Shakespeare, and he sees that

Milton in every instance pursues his imagination to the utmost.

A conclusive and

penetrating remark: Milton is godlike in the sublime pathetic.

As usual, at least some

tenor of Keats’s insights fall from the critical discourse of his acquaintance, William Hazlitt, who writes that, in a particular

passage about Satan, the mixture of beauty, of grandeur, and pathos, from the sense of

irreparable loss, of never-ending, unavailing regret, is perfect

(from Hazlitt’s Surrey

Institution lecture On Shakespeare and Milton

).

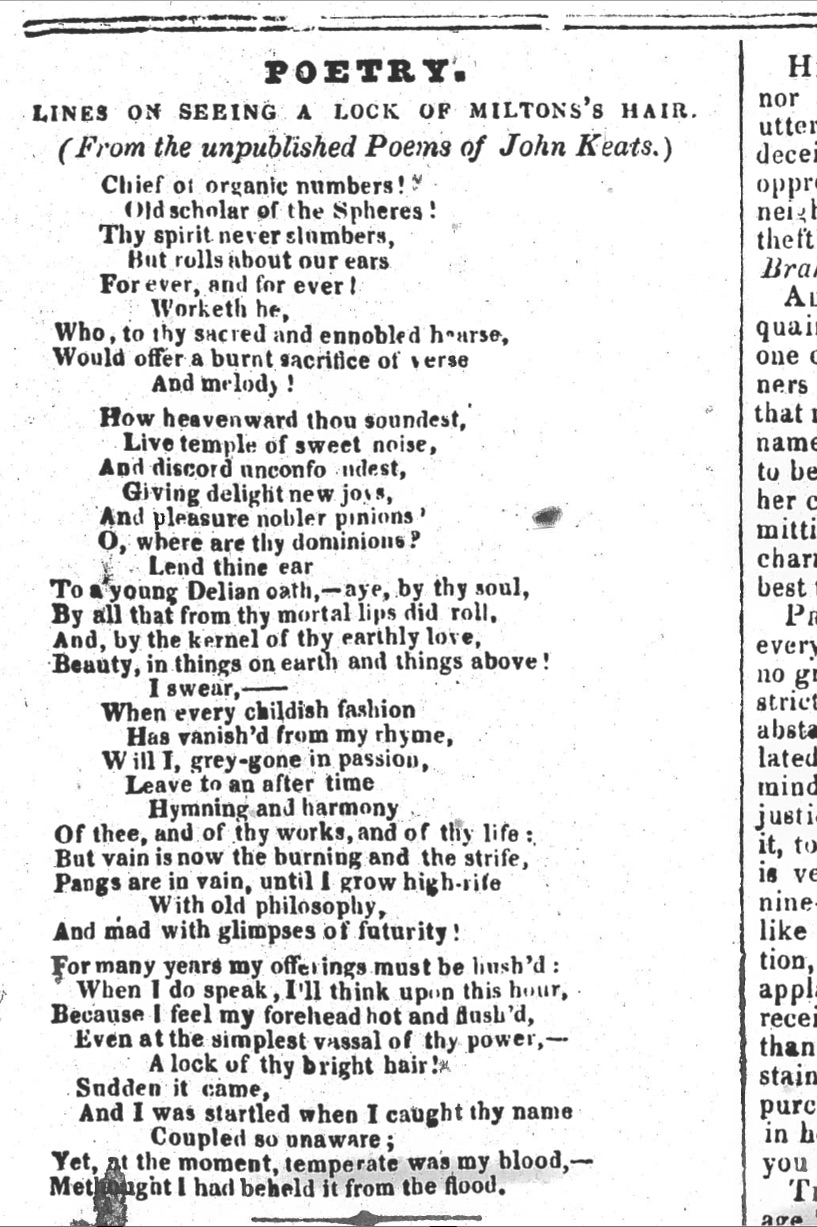

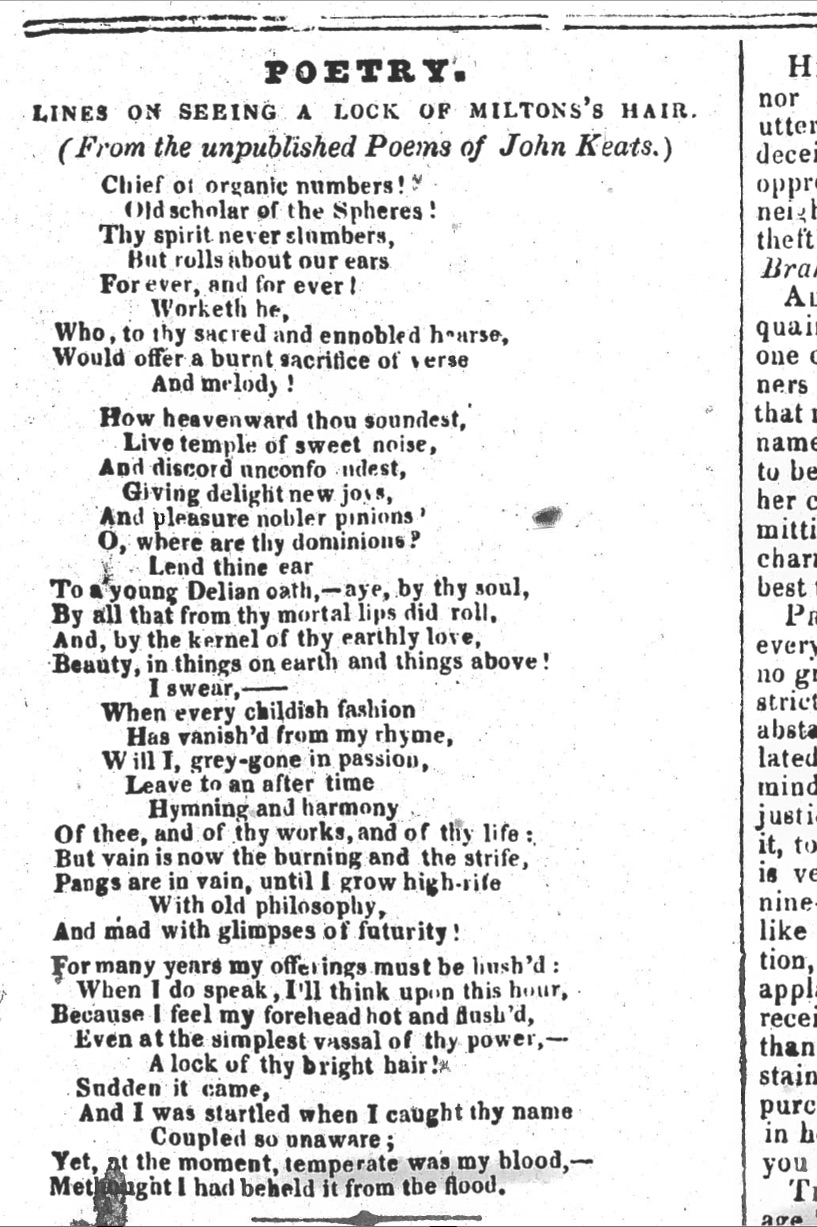

As in many of Keats’s early occasional poems, Lines on Seeing a Lock of Milton’s

Hair once more (and rather unevenly) reduces to an expression of Keats’s desire

to be an enduring poet—he feverishly pines for Miltonic poetic maturity, so that he

can leave

behind what he revealingly calls the childish fashion [in] my rhyme.

This suggests a

fairly realistic self-assessment of his poetic progress thus far. Most importantly,

though,

after a somewhat fallow period, Keats hopes to apply his poetic aspirations with renewed

ardor: writing to his brothers on 24 January, he says, So you see I am getting at it, with

a sort of determination & strength.

Keats at this time also notes that his friends do quite a bit of bickering. He particularly mentions Benjamin Robert Haydon, Hunt, and John Hamilton Reynolds, with Haydon often in the middle of most squabbles. Keats looks down upon those who seize upon the faults of others, since all have faults. Keats even hopes, in the future, to be peacekeeper between his friends. He also has concerns for his younger brother, Tom, whose spitting of blood continues, and signals consumption.

As mentioned, Keats articulates the need to go in a different direction from overly Huntian Endymion (which he begins to see through the press), and he hopes to do so with a more Miltonically-inflected poem, Hyperion. Endymion has become a project (an exercise in perseverance, really) that Keats is eager to complete—and forget about. Keats has just submitted his revisions to the first book of Endymion to his publisher. In more ways than one, the Hyperion project (in tone, style, and intention) is the anti-Endymion, though, despite great work and a great leap in poet accomplishment, after two starts, he gives up on the poem. It may have become too Miltonic for him. [For more on Milton and Keats, see 19 September 1919.]

And so, partially through Haydon, Keats begins

to understand that Hunt’s influence is not helpful

for his own poetic progress. He recognizes a change has taken place in my intellect

lately—I cannot bear to be uninterested or unemployed

(letters, 23 Jan 1818). As usual,

his reading of Shakespeare is in part behind

his poetic inspiration, and (not for the first or last time) reading King Lear reminds him of the profundity of artistic achievement when turned upon the

depths of human nature. [For more on Keats and Shakespeare, see April

1817 and 2 October 1817.]

As suggested above, contact with and reading William

Hazlitt influences Keats’s poetics. (Keats is especially interested in Hazlitt’s

observations and judgments about poetic merit and distinction, ranging from Elizabethan

writers and Shakespeare to Wordsworth.) Keats comes to particularly focus on what

qualities

give poetry lasting eminence, and here, along with Shakespeare, Milton’s accomplishments

intrigue him. Keats also says that he sees a good deal of Wordsworth

about this time (letters, 23 Jan), and in a

few months Keats will attempt to articulate the differences between Milton and Wordsworth’s

forms of greatness and genius.

All of this confirms that Keats’s progress is significantly determined by a deliberate and developing engagement with, along with a few others, the work of Shakespeare, Milton, and Wordsworth—and, as mentioned, a diminishing engagement with Hunt. How very deliberately and with what impressive critical insights Keats studies these great writers (in an attempt to understand both the nuts-and-bolts and general sweep of their work) should never be underestimated. Such understanding will, literally, underwrite the qualities of his premier achievements as a poet.

To put it too simply: for Keats, Milton’s work and vision (and particularly Paradise Lost) is nothing short of wondrous, but Milton’s style turns out not to be what Keats can naturally embrace; Wordsworth’s poetry is, for Keats, likewise often remarkable, especially in its philosophical representation of loss, mortality, nature’s forms of permanence or moral reflection, and suffering, but Wordsworth’s insights, negotiated so strongly through such an elevated, personalized subjectivity, do not align with Keats’s style of embracing a subject; but Shakespeare’s accomplishment, in his startling ability to easefully move between conflicting (and conflicted) subjects, characters, ideas, and emotions, yet without any settled sense beyond the beauty of expression itself, elevates Keats’s poetic ambitions.

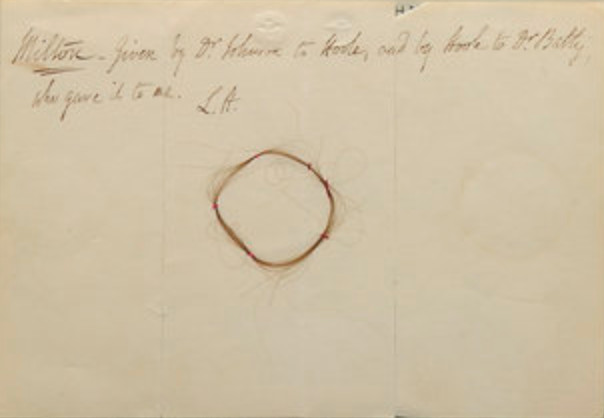

*Hunt is an avid hair collector. His Book of

Hair

(now at the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas, Austin) contains the locks

of

twenty-one famous persons. The Milton lock has

not been authenticated, though others have. Hunt’s collection ends up including locks

of Keats

himself, as well as clippings from Wordsworth, Robert Browning, and Percy Shelley.