2 October 1817: Shakespeare’s Birthplace & Importance

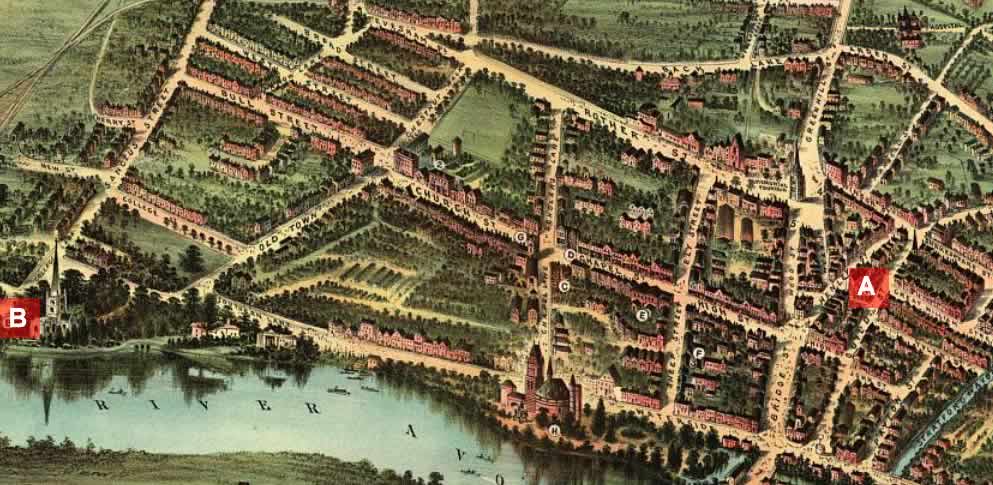

Stratford-On-Avon: Shakespeare’s Birthplace (A) and Holy Trinity Church (B)

In early October 1817, Keats (aged 21) travels about thirty-five miles or so to Stratford from Oxford with his friend, Benjamin Bailey, with whom he has been staying since 3 September. Bailey is studying for his holy orders while at Oxford University. They stay two days in Stratford; Keats will be back in London by 5 October. The month at Oxford—staying with Bailey in his rooms at Magdalen Hall—is a short but relatively settled period.

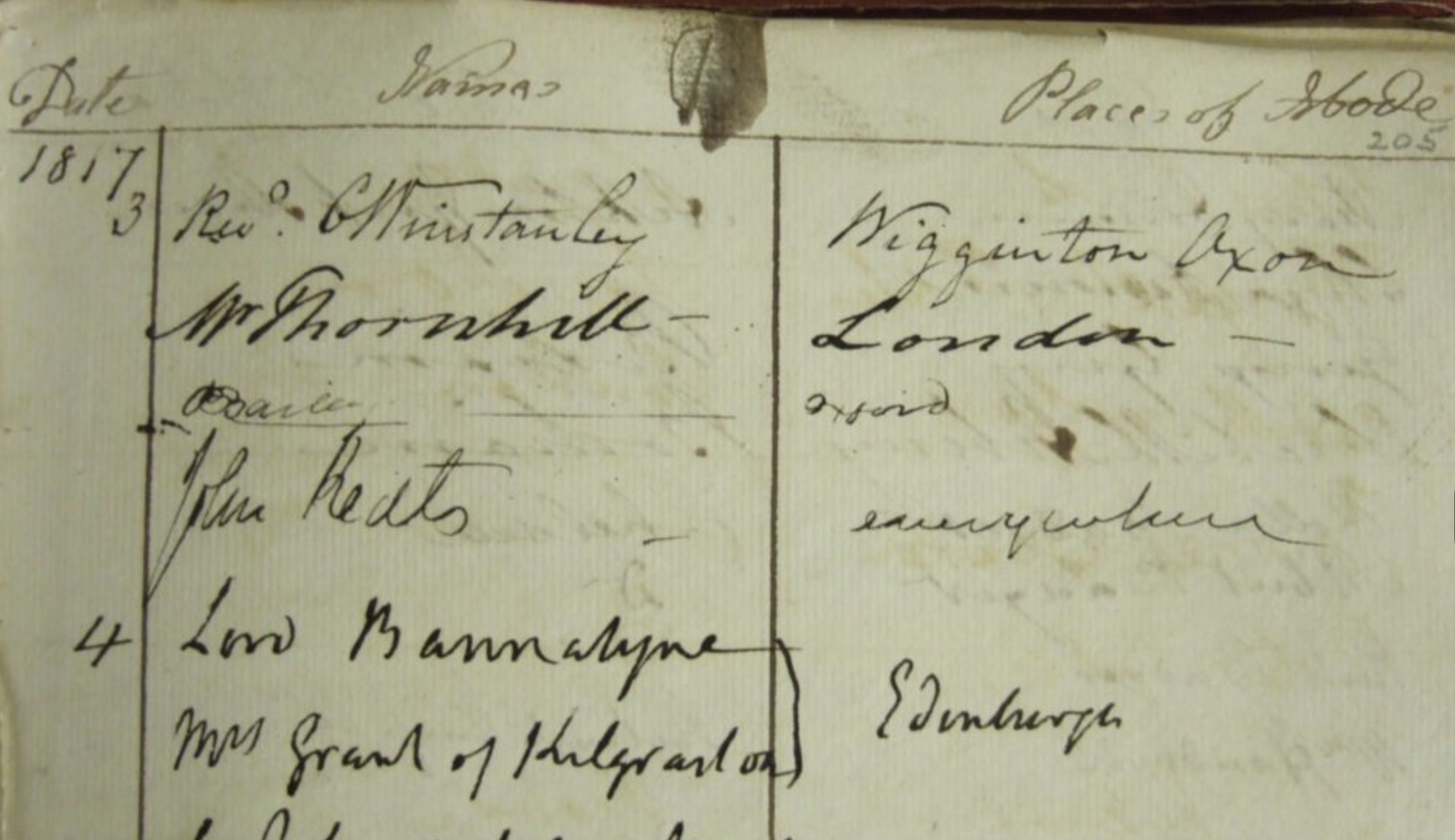

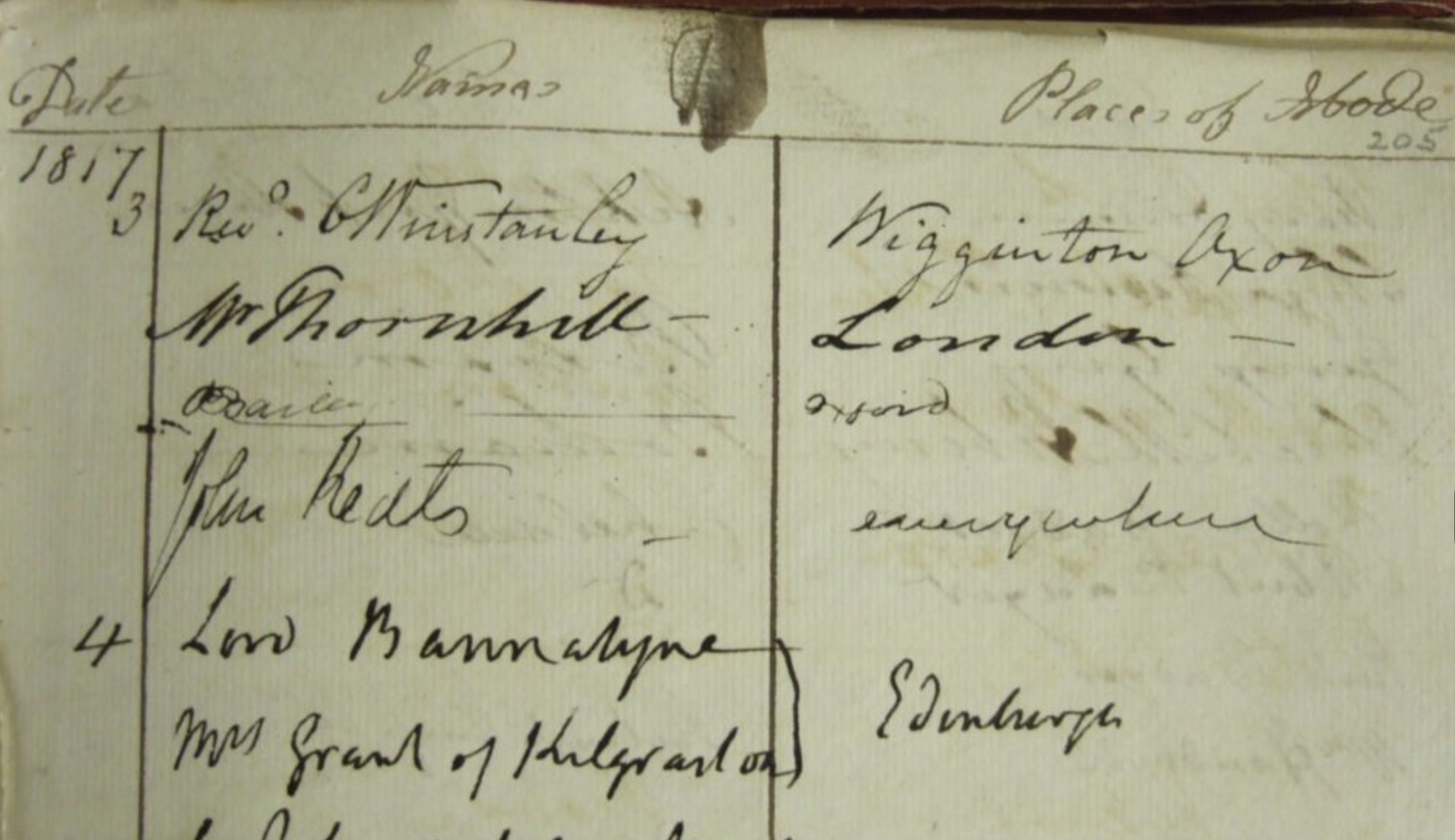

In Stratford, Keats and Bailey see a statue of

Shakespeare, and they visit the room where

Shakespeare is apparently born. They sign the visitor book of the house, and where

Keats is

supposed to enter his Place of Abode

in the guest book, he writes

everywhere

—even here, fooling around, Keats, is ever the negatively-capable chameleon

poet. They also write their names on the wall along with the thousands who have already

done

so in homage to the Bard, and then they go to Holy Trinity Church, where Shakespeare

was

baptized and buried; and, once more, in signing the church visitor book, beside his

name he

writes the Latin equivalent of everywhere

: ubique. Keats is back at Hampstead

by 5 October to meet up with his younger brothers, Tom and George, who have been holidaying in France.

everywhere.The full book is at the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust archives (DR185/1). Click to enlarge.

While staying with Bailey, Keats and scholarly Bailey work steadily at their own projects (Keats on Endymion, mainly Book III); but, while enjoying Oxford’s ambiance, they take plenty of time to discuss literature, philosophy, and religion, as well as to read poetry and criticism together. Keats will leave Oxford fortified and challenged by ideas about the imagination, theology, Wordsworth, Milton, Shakespeare, and Dante, as well as forging a deliberate and important understanding of William Hazlitt’s philosophy and criticism. In subsequent letters to Bailey, we get a picture of the topics they must have discussed, as well as the complex depths of the discussion; some of Keats’s most important thoughts subsequently turn up in his few letters to Bailey (see, for example, Keats’s letters of 8 Oct, 22 Nov 1817, 13 March 1818). Perhaps most importantly, Bailey’s ideas about the function or meaning of faith—a faculty by which to perceive truth?—almost certainly raises Keats’s thoughts, since, for him, truth is more aligned with imaginative capabilities. [For an overview of Keats’s ideas about religion, see 18 December 1795.]

Shakespeare is easily Keats’s most

venerated literary figure—his literary presider, to use Keats’s own term of privilege.

Almost

all of Shakespeare’s works are mentioned,

alluded to, or quoted directly in Keats’s letters—Shakespeare seems to float to the

surface of

Keats’s thoughts in every possible situation, expression, or play of words. For example,

at

the end of his life, when his health is weak and he cannot muster the strength to

write

poetry, Keats is at a loss on how to express his situation to his love, Fanny Brawne; he can only write, Shakespeare always sums up

matters in the most sovereign matter

(letters, August 1820). Three years earlier, when

his writing career is mainly ahead of him, he concedes the idea (derived from Hazlitt) that Shakespeare may be enough for

us

(letters, 11 May 1817). Keats’s very good friend, Benjamin Robert Haydon, will, in his autobiography, recall that

the most he ever got out of Shakespeare was in his conversations with Keats.

Keats believes something that few would dare to say. In the context of moving beyond

Endymion’s inadequacies, he writes, I have great reason to be

content, for thank God I can read, and perhaps understand Shakespeare to his depths

(letters, 27 Feb 1818).

Purposeful evaluation of Shakespeare’s

literary qualities is central to Keats’s progress. This is especially clear given

that,

significantly, Keats’s poetics generally drive and are in-advance of his poetry’s

development.

Two of Keats’s most important critical insights relative to his progress come in the

context

of Shakespeare. First, in attempting to explain greatness in literary achievement,

Keats

formulates his idea of Negative Capability when, with subtle

intensity, Beauty & Truth

collapse as indistinguishable and eclipse all other

considerations, including doubt, mystery, fact, reason, or any disagreeables

; Keats

notes that King Lear exemplifies such qualities. About 200

words later, Keats writes that Shakespeare possessed [these qualities of literary

achievement] so enormously

(letters, 21/27 Dec 1817).

Second, ten months later, Keats describes the poetical Character

he suffers to

achieve. He distinguishes his own type from the wordsworthian or egotistical sublime; which

is thing per se and stands alone.

Keats’s poetical sort is otherwise: it is not

itself—it has no self—it is everything and nothing—It has no character—it enjoys light

and

shade; it lives in gusto, be it foul or fair, high or low, rich or poor, mean or elevated—It

has as much delight in an Iago as an Imogen. What shocks the virtuous philosopher

delights

the camelion Poet [. . .] A Poet is the unpoetical of any thing is existence

(27 Oct

1918). Not only is some of the key wording—a thing per se and stands alone

—a direct

reference to Troilus and Cressida (1.2.15), but also the

contrasting characters—treacherous male Iago vs Othello and tender female Imogen vs

Cymbeline—come from the range of personality and voice that Shakespeare somehow perfectly ventriloquizes.

Suffice it to say, Shakespeare inhabits a

fair amount of Keats’s middle and later poetry, beyond the obvious inhabitation of

Shakespeare

manifest in his letters—yes, inhabitation.

It is not just the case that we encounter

many and varied allusions to Shakespeare’s work, thus making Keats merely another

reader or

user of Shakespeare’s phrasing. Keats’s relationship with Shakespeare is different.

His

deliberate, detailed, deep, and ingenious study of Shakespeare urges him to a particular

poetic position as well as to a personal realization, that he lives life and then

represents

life in a way like Shakespeare. The totality of this somewhat bold conclusion takes

us to something simple to say, yet complex to fully apply: Over a fairly short period,

Keats

evolves a consciousness of himself as experiencing and responding to the world—of

feeling and

thought, of sensation and reflection, of mutability and permanence, of suffering and

joy—in,

as suggested, a manner like Shakespeare. When Keats is just about to write his greatest

poetry, and in the context of observing how few people actually see into the complexities

of

life’s mysteries, Keats comes up with a remarkable insight, that Shakespeare led a life of

Allegory

—Shakespeare’s works are the comments on it

(letters, 19 Feb 1819). This,

too, is how Keats’s views his own life relative to his work (his letters make this

clear), and

what he wants to accomplish in his poetry.

For Keats, the initial step is to embrace and employ a faculty in fact quite natural

to him:

Shakespeare’s camelion,

empathetic

imagination (letters, 27 Oct 1818). Keats comes to realize that, for him, the drama

in poetry

is not for opinion, for bullying, for self-indulgence, for showy artistry, or for

simple,

random amusement; it is not for final reasoning or clear, absolute reckoning. Poetry

should,

rather, invite the reader into the moment or scene with imaginative felicity and with

unselfconscious, unobtrusive language, to a point where the subject, rendered with

controlled

intensity, is all, even in (or maybe especially in) its inconstancy or uncertainty,

to where

some essence of humanity can be represented. This he begins to achieve in his poetry

in the

early months of 1819. Keats will compose enduring, deep poetry in lines that no longer

linger

in verdurous bowers or that droop pleasingly over delicate, dewy buds. Which takes

us to what

Keats is writing in October 1817.

During his month at Oxford, Keats works steadily to complete the third book of Endymion, though by the end he is dissatisfied with it. He writes

to his friend, the historical painter Benjamin Robert

Haydon, My Ideas with respect to it I assure you are very low [. . .] I am tired

of it

(28 Sept 1817). He goes on to quote from a letter written to his brother, George, earlier, in the spring, where he worries over

poetical fame

; he sees Endymion as a trial of my

Powers of Imagination

and a long poem a test of Invention which I take to be the

Polar Star of Poetry [ . . .].

In contrast to the relatively structured month-long peace at Oxford and the profitable

and

ranging discussions he had with the scholarly, unassuming, and somewhat conservative

Bailey, back in Hampstead Keats almost immediately

writes to Bailey: he is disgusted

with literary Men

and their petty jealousies

(8 Oct 1817).

At this moment, Keats hopes he can maintain poetic independence, particularly from

Leigh Hunt, even if it is Hunt who, a year earlier,

more or less launches Keats’s poetic career. Keats hears that Hunt, behind his back,

may be

acting somewhat condescending toward Keats’s poetic work on Endymion, as if he assumes some ownership of Keats’s quality and direction. Writing

to Bailey, Keats fears that his Reputation

will be set as Hunt’s callow student (8 Oct 1817).

Keats’s fear in fact becomes too true: less than a year later, in the August 1818

issue of

Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, Hunt is portrayed as Keats’s prototype,

with little Johnny

Keats

adopting Hunt’s loose, nerveless versification, and Cockney rhymes.

Endymion comes off

terribly: it is portrayed as calm, settled, imperturbable drivelling idiocy.

And just

weeks after the attack by Blackwood’s, the April edition of

Quarterly Review is finally released, and is just as

damning, calling Keats an imitator and copyist of Mr Hunt

—Hunt’s simple

neophyte.

Endymion is mocked

for its diction and versification, and for the way the convenience of a rhyme excitedly

determines direction. Keats, the review notes, wanders from one subject to another, from

the association not of ideas but of sounds, and the work is composed of hemistichs

which, it

is quite evident, have forced themselves upon the author by the mere force of the

catchwords

on which they turn.

Most of this is, unfortunately, correct. Endymion is overly and often arbitrarily poeticized, with too many moments forced and many others seemingly random—in many passages, direction does seem driven by sound (rhyme) rather than sense or story. Superfluous details and description awkwardly bump up against vague sweeps of sentiment. Thus aspects of Hunt’s influence are indeed present. Keats knows that he will have to go in other directions to achieve anything like the poetic independence and greatness he has been thinking about for over a year. In fact, it could be argued that in proofing and revising Endymion for publication, Keats faces its generally ineffectual character, thus motivating significant change in direction.

It can be conjectured that during his time with Bailey in Oxford, and given the larger, deeper topics they discussed, Endymion’s relatively insubstantial quality and purpose becomes increasingly apparent. This is a key realization in terms of Keats’s future poetic directions. The good will come after the bad and the ugly.