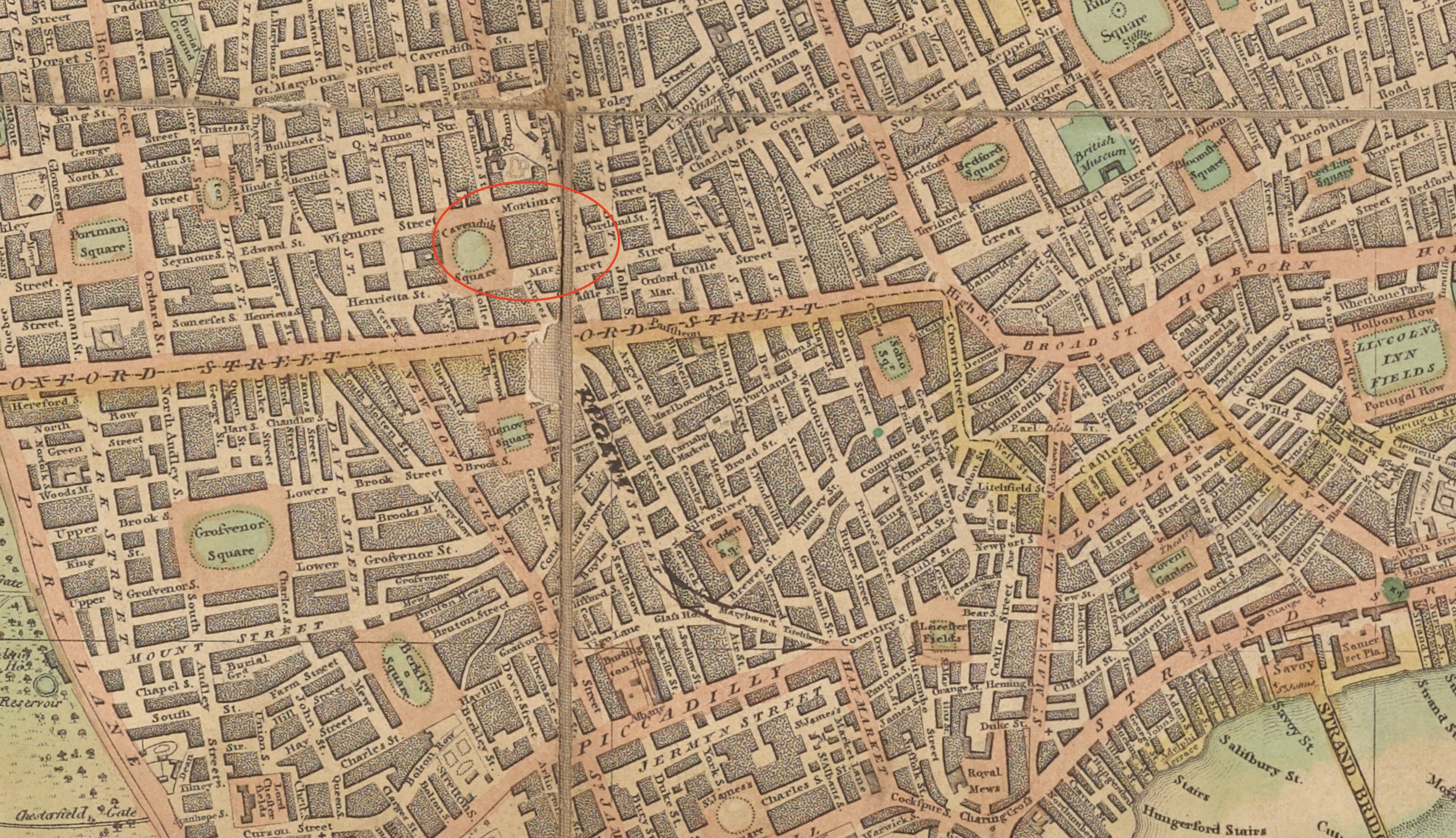

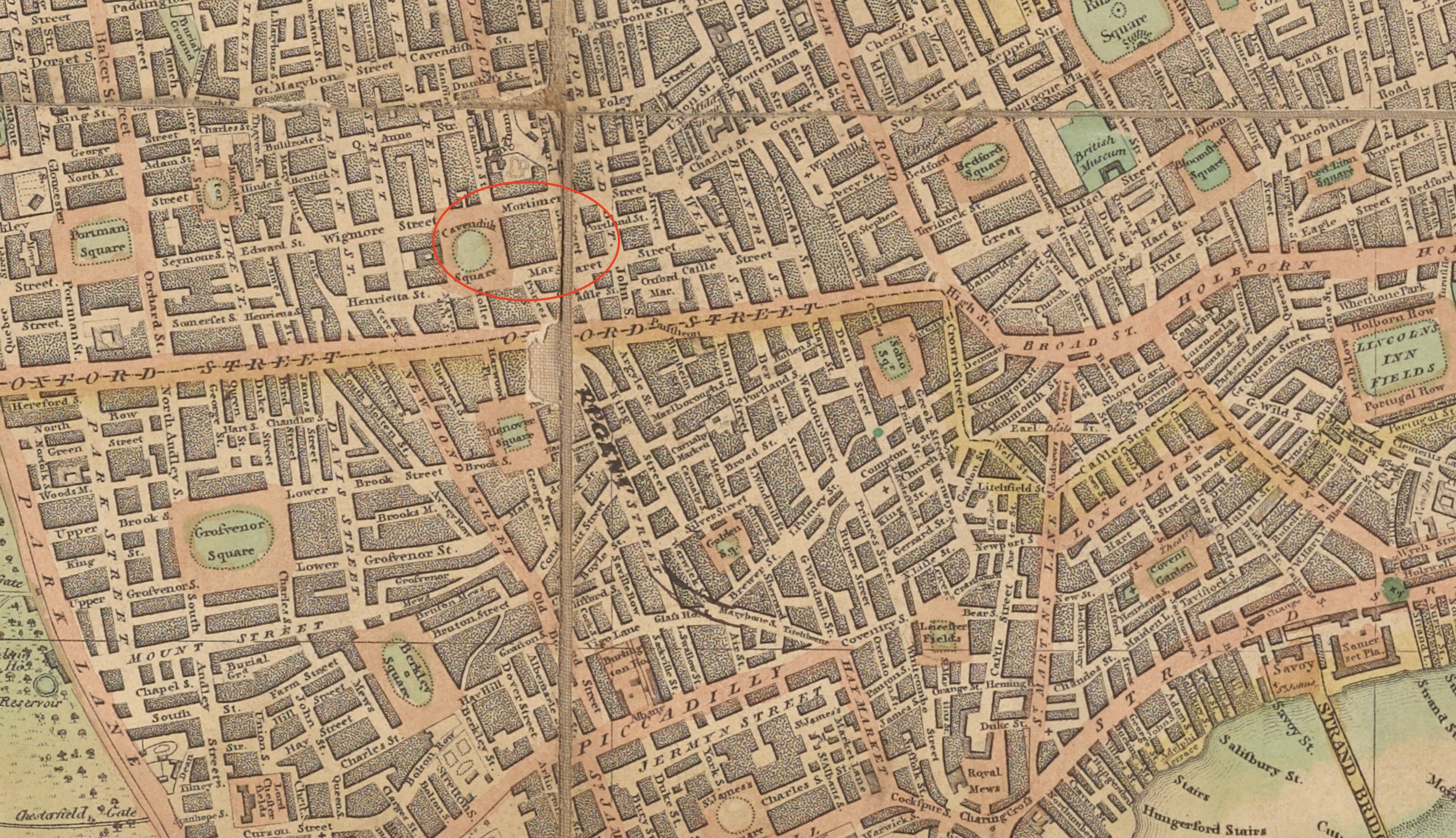

3 January 1818: Keats Calls on Wordsworth

48 Mortimer Street, Cavendish Square, London

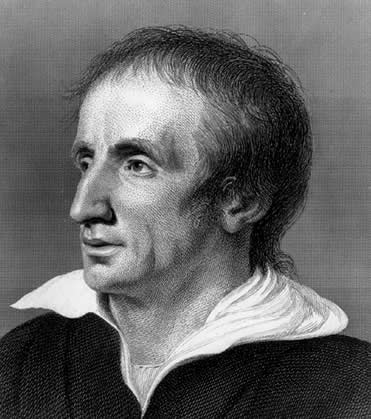

Keats, aged twenty-two, stops by to see the great poet William Wordsworth, aged forty-seven, at 48 Mortimer Street,

Cavindish Square. Wordsworth is visiting London for about a month. During this period

in early

1818, Keats records he sees a good deal of Wordsworth

(letters, 23 Jan)—perhaps five or

six times. On this Saturday night, Keats (after being kept waiting a bit) finds Wordsworth

formally dressed and on his way to visit John Kingston, a civil servant and Wordsworth’s

superior at the Stamp Office. Keats is not altogether happy with the encounter; he

gets the

sense that Wordsworth is acting somewhat beneath himself by pandering to Kingston

after an

awkward encounter with that Keats witnessed some days earlier.

Keats is originally introduced to Wordsworth by his friend, the historical painter, Benjamin Robert Haydon, in the last few weeks of December 1817. Haydon, at the time almost a worshipper of Wordsworth, had painted Wordsworth’s portrait and had also made a life-mask of him in 1815. (Haydon also does a life-mask of Keats, likely in December 1816.) Haydon will include both poets in a crowd scene in one of his large historical paintings that he is currently working on.

We have to imagine what meeting the famous Wordsworth meant for Keats. On one level, Keats’s regard for Wordsworth has to be reverential. But more significantly in terms of Keats’s poetic development, coming to critical terms with Wordsworth’s poetic depth, style, and reputation is crucial in establishing his own poetical character. No other contemporary poet held such an ambivalently powerful sway over Keats. (See 16 December 1817 for more on Keats and Wordsworth.)

Keats’s poetics intensifies and grows more sophisticated at this time, just when he

is seeing

much of Wordsworth and while he is discussing

art, poetry, and publishing (and, quite likely, Wordsworth) with the likes of Haydon, Joseph

Severn (another artist), James Rice, William Haslam (an old friend and stellar supporter),

John Taylor (one of his publishers), Benjamin Bailey (scholar), Leigh Hunt, and William

Hazlitt (literary critic). In particular, Keats’s singularly important theory of

Negative Capability

is expressed about ten days or so after his first

meeting with Wordsworth (letters, ?27 Dec 1817); and is done so in light of critically

negotiating Wordsworth’s strong, subjective command and his significant insights.

For

Wordsworth, this is a seeing-into the life of things, which is how Wordsworth puts

it in what

for Keats is Wordsworth’s most revelatory poem, Tintern Abbey.

To express it too simply, part of Keats’s negative reaction is not so much to the

subjects

Wordsworth explores in much of his best poetry—nature, human nature, suffering, loss,

the

synthesis of feeling and thought—but to how the older poet channels that exploration

through

legislating subjectivity. Keats crucially understands that poetically representing

these

subjects must be part of his own poetic progress, but he has yet to find a sustained

voice or

forms or subjects through which to do so.

Keats attempts to determine if Wordsworth’s

vision is vast or limited, whether it is truly grand or too brooding and inward. But

what

Keats does at least know is that his own poetic development will be determined more

by

assuming the subject of the poetry than featuring the poet’s subjectivity. This said,

the

lyric mode Keats assumes in most of his greatest poetry will mold the presence—in

thought,

sensation, and voice—of a particularized, responsive, probing speaker. Some of the

condemnable

ideas about Wordsworth no doubt derive from Keats listening to Hazlitt, his critical mentor, who, along with a few other

commentators, begin to translate Wordsworth’s lyrical subjectivity as egotism,

which

Keats is, at least initially, keen to contrast with an Elizabethan poetic temper.

But what

Keats also realizes is obvious: Wordsworth profitably, poetically, complicates human

experience in exploring, say, the meaning of loss or the tempered power of nature;

and Keats,

following him, will in his best poetry do the same, and likewise he will do so in

a lyric

form.