The third week of December 1817: Keats Meets Wordsworth

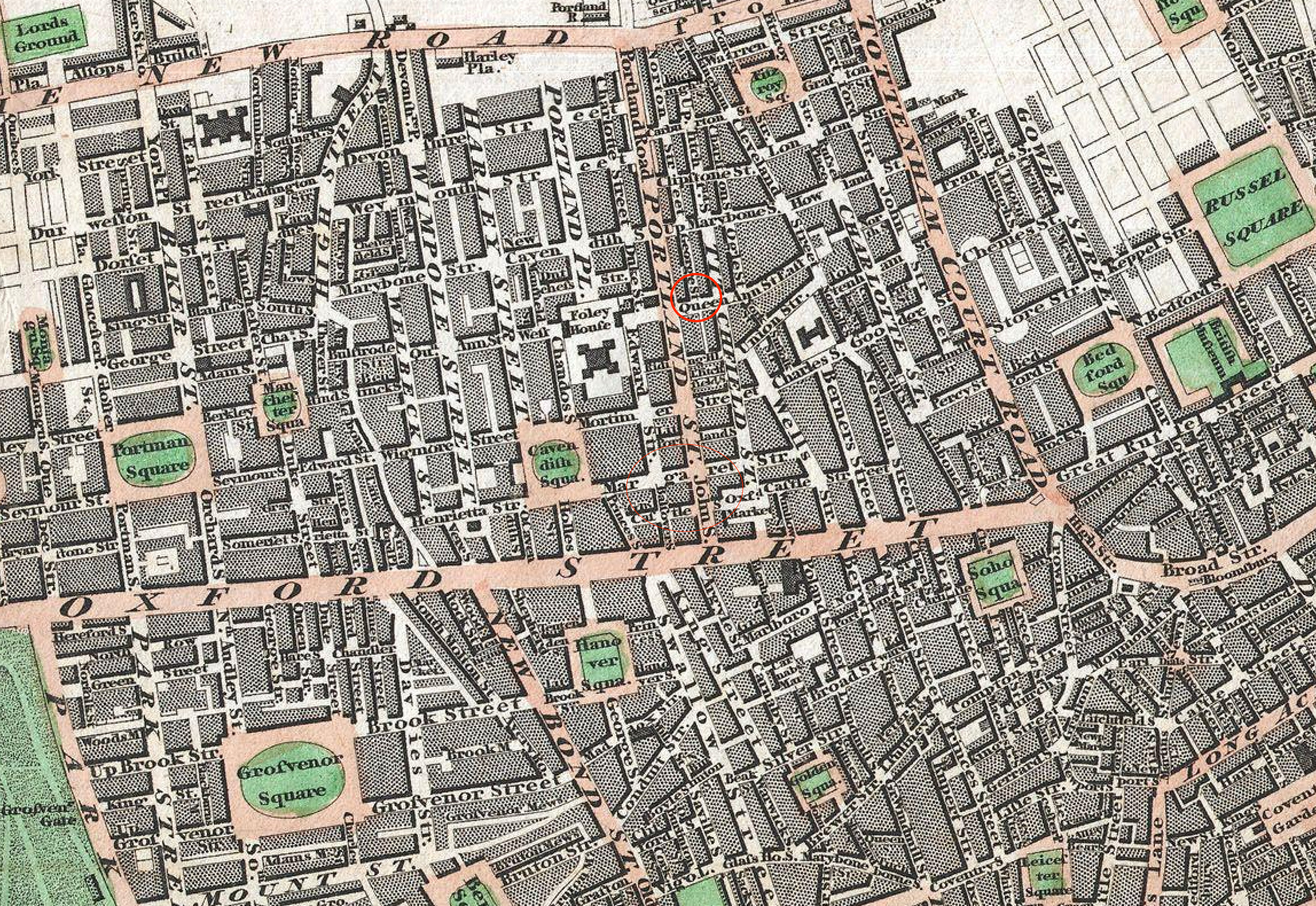

28 Queen Anne Street, London

The third or fourth week of December: Keats goes with his close friend at the time, the painter Benjamin Robert Haydon, to 28 Queen Anne Street, to meet William Wordsworth at the residence of Thomas Monkhouse, a well-to-do London merchant and cousin of Wordsworth’s wife, Mary. Haydon arranges the meeting. Wordsworth is apparently in town to do some business that likely involves lingering family money matters related to the death of Wordsworth’s brother, Richard. Initially, he meets up with another brother, Christopher.

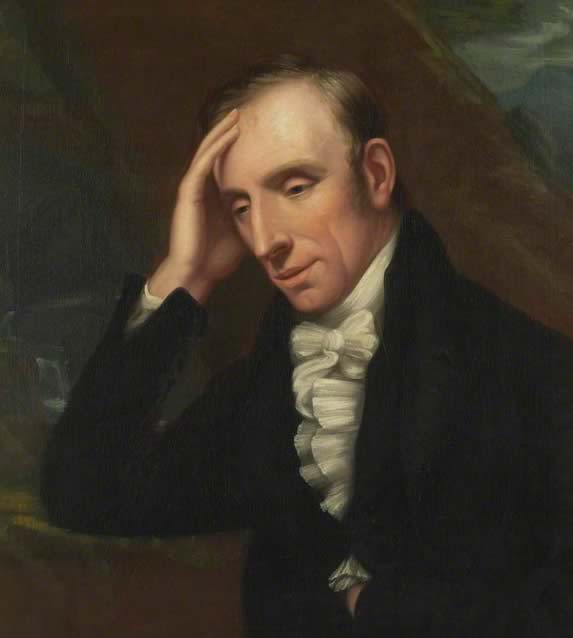

In December, Wordsworth, aged forty-seven, will sit for Haydon as Haydon sketches him (on two occasions, it seems: 2 and 22 December, at Haydon’s studio in Lisson Grove); Wordsworth will read some of his poetry aloud during these sessions, and Haydon and Wordsworth seem to enjoy mutually praising each other in their high calling. Haydon at this point is fully attuned to Wordsworth’s superior gifts; the trouble is, Haydon is likewise a fan of his own artistic merit and (he believes) destined greatness, though in terms of artistic history his misses the mark.

Given Wordsworth’s status as perhaps the most important poet of the era, this meeting

would

have been an extraordinary moment for the aspiring young Keats, who is struggling

to find a

poetic voice; and it is a voice and poetic character that Keats will eventually conceive

of in

light of (yet contradistinctive from) Wordsworth’s. In just under a year, just as

Keats is

about to take a remarkable leap in the quality and nature of his poetry, Keats sees

himself as

a camelion Poet,

to be distinguished from the wordsworthian or egotistical

sublime

(letters, 27 Oct 1818). To reduce the differences between the two: Keats’s

representation of poetic insight is via an empathetic, sensual, and profitably variable

imagination; Wordsworth’s is through a legislating subjectivity and subtle, yet deeply

profound, sense of the self and its foundations.

At this meeting at Monkhouse’s at Queen Anne Street, Keats, when prodded by Haydon,

recites

by memory some of his recent poetry to Wordsworth—a passage from Book I of Endymion, the so-called Ode or Hymn to

Pan (lines 232-306). According to Haydon, Wordsworth comments that the passage is

a Very

pretty piece of Paganism

; Haydon believes that Wordsworth’s pronouncement is made with

some indifferent or negative intent—it is unfeeling

and disappointing—but he records

this sometime later when his regard for Wordsworth is waning (by 1820 he is upset

that

Wordsworth won’t lend him some money). The word pretty

is perhaps something of a

problem, since it could suggest skill, artfulness, and something pleasing, yet also,

used

ironically, something trifling. In truth, the Pan passage, though it hints toward

a kind of

Wordsworthian ethos of nature’s creative and knowing immensity, does indeed wallow

through

some paganisms in its rather fruity (and Huntian) pastoral terms of reference and

phrasing,

like voices cooingly ’mong myrtles,

enmossed realms,

ripen’d fruitage,

yellow girted bees,

snouted wild-boars,

poor lambkins,

fairest blossom’d beans and poppied corn,

and chuckling linnet

; there’s even a

ram bleating because of the snapping shears as well as a bit too much verbiage of

trembling,

creeping, budding, leaping, swooning, withering, and the like. It’s not bad, but it’s

not

great, though it perhaps vaguely hints of greatness to come. As far as we know, Keats

never

directly addresses Wordsworth’s possibly disparaging comment, though Haydon seems

determed to

believe that Keats was hurt deeply by it.

Well, hurt or not, Keats sees Wordsworth a number of times over the next few weeks. He also attempts to call upon Wordworth on a walking tour through northwest England into Scotland, in late June 1818 (see 26 June 1818 for more on this), so this first meeting, no matter what was said or how it was said, did not discourage Keats from wanting some contact with Wordsworth.

As suggested, in his poetic progress, Keats’s grappling with and attempts to understand

Wordsworth’s poetic style and depth is both

central and problematic: Wordsworth’s growing conservatism and protected sense of

self-worth

bothers Keats, but Keats also realizes Wordsworth’s penetrating insights about the

nature and

mystery of the human heart, loss, and suffering are to be praised, if not emulated—if

not in

style, at least in spirit, scale, and depth. Keats begins to consider the possibility

that

poetry might reflect philosophical qualities that can unite, without contradiction,

both

disinterestedness and intensity. In March 1819, during the period of Keats’s greatest

composition, Keats states that he admires half of Wordsworth

—presumably early

Wordsworth, or Wordsworth the poet who has not pandered his poetry to petty subjects

or

compromised his beliefs with Tory values and connections.