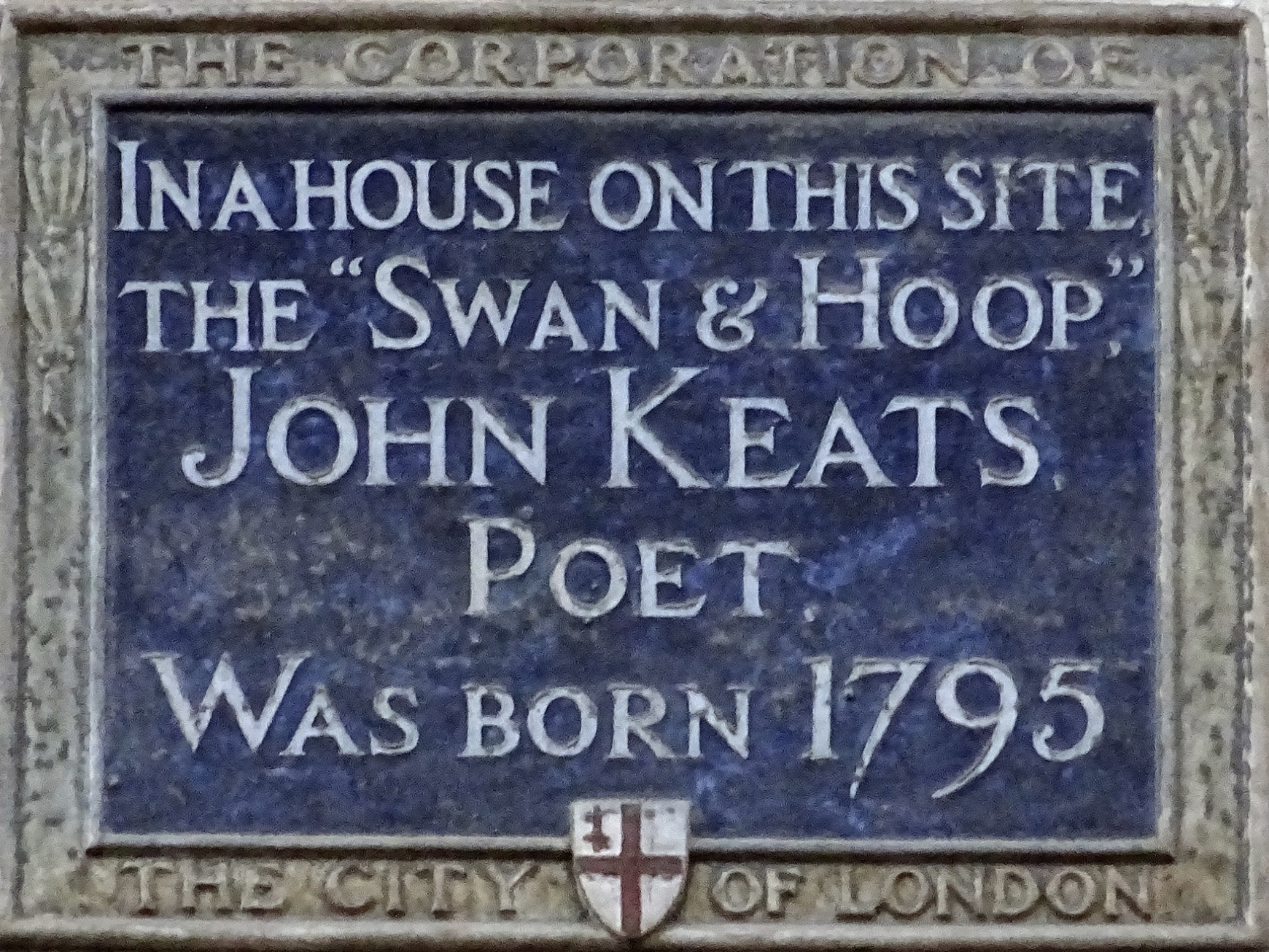

31 October 1795: Keats is Born into a Growing, Successful Family

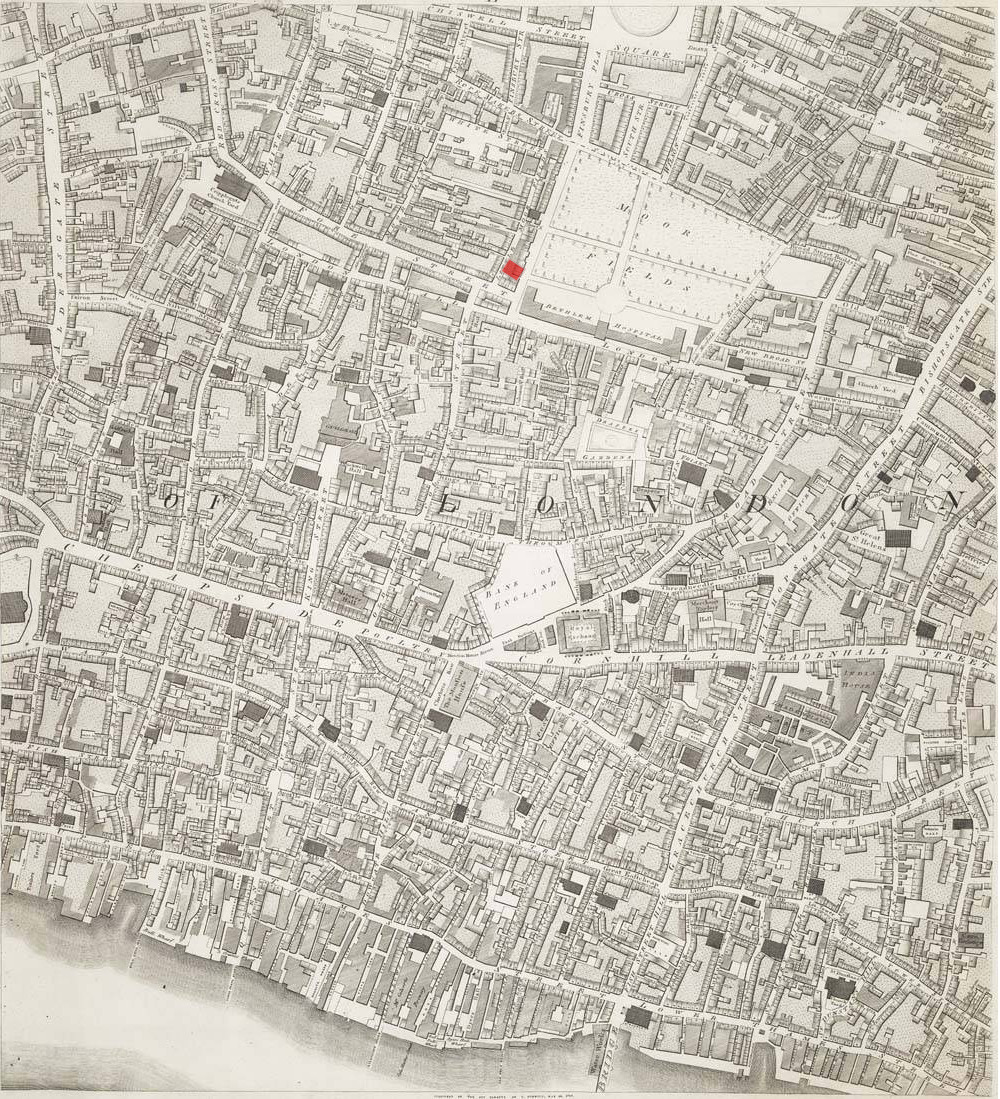

Swan and Hoop Inn and Livery Stables, 24 Moorfields Pavement Row, London: where Keats is likely born

Keats is likely born at the Swan and Hoop Inn and Livery Stables, 31 October 1795.

He may have

been born two months premature, at least according to Keats’s friend, Leigh Hunt—a seven months’ child,

he writes in his essay Mr.

Keats with a Criticism on his Writings,

from Lord Byron and Some of his

Contemporaries (1828), seven years after the death of Keats. Hunt also writes that Keats

was born on 29 October 1796, which casts some doubt on Hunt’s facts, or maybe on the

exact date

of Keats’s birth. To put this moment of British Romanticism into generational perspective,

this

also happens to be the month of Samuel Taylor

Coleridge’s unfortunate marriage to Sarah Fricker.

Some background: Keats’s mother’s parents—John

and Alice Jennings—run and own (leasehold) that successful livery stable business,

going back to

1774, when the two get married. Keats’s father, Thomas

Keat[e]s (the spelling is inconsistent at this point), first works at the livery stable,

becomes head ostler, then marries his boss’ daughter (Frances) in October 1794 (she is nineteen; he is twenty; they get married beyond their

parish, at the fairly voguish church, St George’s in Hanover Square, with, it seems,

no family

witnesses); Keats will be born just over a year later. After the retirement of Alice

and John

Jennings, son-in-law Thomas takes over the business in 1802, and it continues to prosper.

The

business is then known as Keat’s [or Keates’s] Livery Stables.

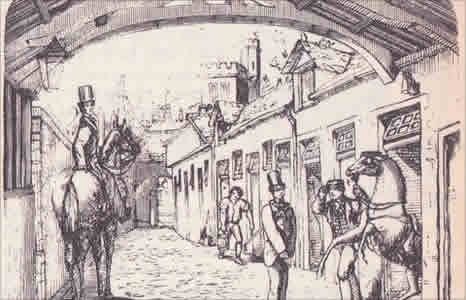

There are more than a quarter of a million horses in the London area at the time, and taking care of them is big business—and essential. Given that a horse can create more than 25 pounds of manure a day, math tells us what the streets might have been like and the magnitude of the job required to keep streets relatively clean. The livery and stable business picked up much of the work required to manage all those horses: grooming, shoeing, harness and carriage repairs, horse and carriage rental, supply associated equipment and feed, stabling and providing stalls. Grooms and stable boys had to be hired and managed, and blacksmiths, leather workers, and farriers were a part of the operation and a network of workers and businesses. There is no full equivalent today, unless you create an all-in-one hotel, restaurant, gas station, car wash, car rental, storage facility, and mechanic’s shop. (Owning a horse in Regency London was actually quite expensive. It is not likely that any of Keats’s London friends owned their own horses or carriage.)

If well run and in the right place, a Regency livery stable business could be lucrative. And, as suggested, John Jennings fairly aggressively develops and expands his business over a number of years, until he and his wife manage well over 100 feet of frontage. The substantial and quickening growth of London at this time is also a significant factor, and the business has an advantageous position to service the ever-increasing traffic. John and Alice thus muster some affluence, and it appears that John in particular enjoyed his money.

Again, a very decent living is created from the relatively large business, and any suggestion that Keats’s family is of a lower social order is wrong—they and the previous generation take advantage of commercial circumstances available to move up emerge out of the lower middle-class.

Keats will benefit from, dare we say, this family excess of capital. What does it provide? First, for Keats, it provides domestic security for the young family; second, it gives the opportunity to attend a superior boarding school (Clarke’s academy; his two younger brothers would also attend); third, he would not have been able to complete full medical training without significant funds; and, last, and significantly, it provides the opportunity for Keats, after that medical training, to pursue his poetic aspirations without having to work. That is, the family money buys Keats time—time, that is, to become a poet, and this it is part of the story of Keats’s poetic progress. But there are limits to these funds: as 1819 moves into 1820, Keats basically lives off diminishing credit from the family legacy, as well as loans from friends; he (and the family trustee, Richard Abbey) is unaware of a fairly decent sum of family money held by the courts. We have to remember that by 1814, when Keats is in the last year of his medical apprenticeship before entering Guy’s Hospital in 1815, all of Keats’s significant elders have passed away.

Little is know for certain about the paternal side of Keats’s family beyond his father, Thomas, except the rather vague suggestion that this particular Keats/Keates family may have been from the Devon area.

And in 1795, the year of Keats’s birth? Prime Minister Pitt’s government, in an effort to curtail the growth of radicalism and reform, introduces laws that ban unlawful assembly and actions than can loosely be deemed treasonable. There are worries over living conditions of the poor, given some outbreaks of famine and the price of food. France invades and captures Holland, but also abolishes slavery in its colonies. Coleridge lectures (with William Southey) in Bristol early in the year. Coleridge and William Wordsworth meet for the first time. Hannah Moore begins publication of Cheap Repository Tracts. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe publishes Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship. Marquis de Sade publishes Aline and Valcour and Philosophy in the Bedroom. Helen Maria William publishes an installment of her letters from France: Letters Containing a Sketch of the Politics in France. Thomas Carlyle and John William Polidori are born, and James Boswell dies. In 1795, the Royal British Navy mandates the use of lemon juice to stop scurvy, and a 56-pound meteorite falls in Yorkshire field; today a structure stands at the point of impact—the Wold Cottage meteorite monument.