December 1802: Solidly Middle Class & Dispelling the Myth of Keats

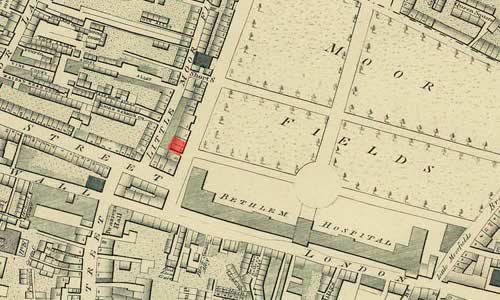

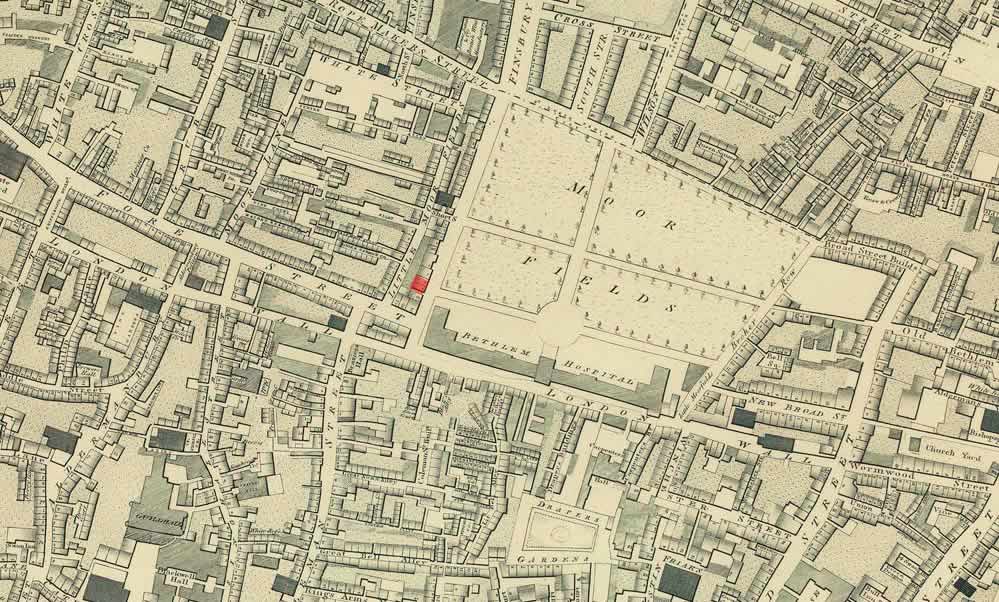

Swan and Hoop, 24 Moorfields Pavement Row, London

Keats’s family moves to the Swan and Hoop Livery Stables, where Keats’s father, Thomas, initially pays rent to his father-in-law,

and will take over property taxes the following year. Thomas, in taking over the business,

subsequently establishes Keat’s [or Keates’s] Livery Stables, Pavement, Moorfields.

From all accounts (and the profits it generated), the fairly large business is successful,

and

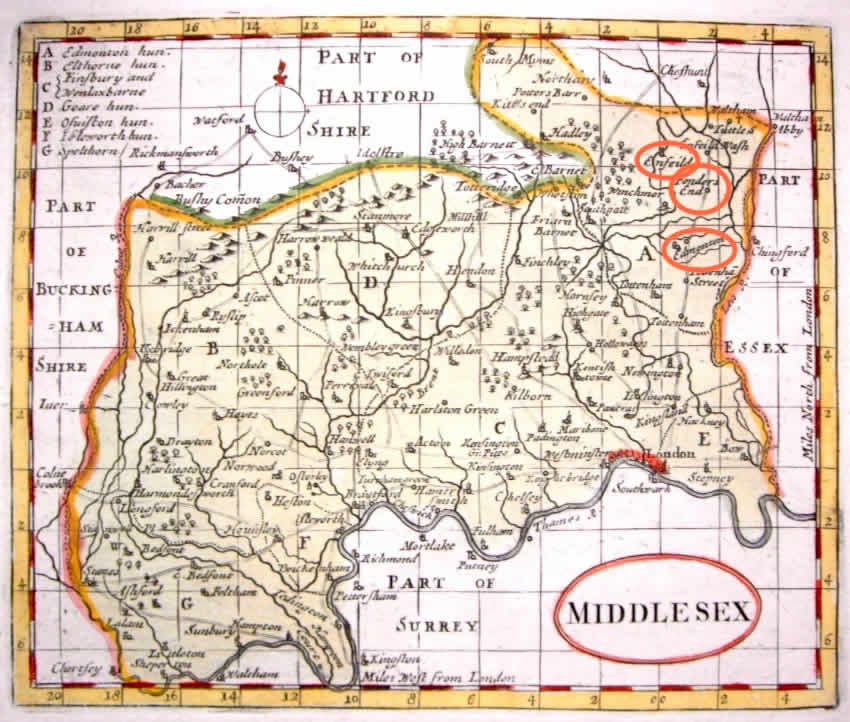

Thomas is a hardworking, honest proprietor. Keats’s maternal grandparents now retire

from the

business and move to Ponders End, Middlesex. Keats is seven years old. Things look

good.

Importantly, family money that eventually comes down to Keats and his siblings after the death of his parents (his father in 1804; his mother in 1810) and his maternal grandparents (John Jennings in 1805; Alice Jennings in 1814) is significant enough that Keats will not have to work in order to support his poetic ambitions, which fully first declare themselves over 1815-1816, just as he is completes about five years of medical training. However, his primary guardian and estate trustee, Richard Abbey (the other guardian dies in 1816), at times seems to keep Keats and his siblings in the dark about family money, though it appears Abbey might not be aware of further funds available to Keats via his grandfather (not known about until after Keats dies; he would likely have got access to these funds upon his 21st birthday). Keats constantly—and sometimes agonizingly—has to meet and deal with Abbey in order to get haphazard installments (later there were also chancery issues with the estate), based on credit from his legacy; this seems to run dry about mid-1819.

That Abbey greatly disapproves of Keats’s decision to be a poet probably does not help Keats in his dealings with the practical, business-driven Abbey, whose main employment is in tea sales—and this seems to prompt Abbey to protect Keats’s younger sister, Fanny, from Keats’s sphere of influence, which comes to frustrate Keats in his final years. Keats’s brothers, George and then Tom, both have stints working for Abbey.

The somewhat popular idea that Keats is from the lower or disadvantaged classes is a nice thought, but far from the truth. With his family’s status and money, his excellent education at Enfield (Clarke’s academy), his extensive training in the medical profession,* and with the remarkable set of people he easefully associates with through Charles Cowden Clarke, and later through poet and celebrity journalist Leigh Hunt after October 1816, Keats is fairly middle class. This does not stop some conservative critics from severely looking down their Tory noses at the young, neophyte Keats when his poetry comes before the public; but this cultural and political pegging of Keats mainly comes from his immediate association with Hunt’s liberal-reformist camp and Hunt’s highly visible public politics, mainly trumpeted via Hunt’s paper, The Examiner.

The other Keatsian myth to be dispelled revolves around the idea of Romantic poet as a self-secluded, sky-gazing, fauna-fawning figure. In fact, the story of Keats’s poetic progress (as reflected in this site) is largely determined by Keats being extraordinarily social during the three or four years leading to his great poetry of 1819—Keats meets and interacts with a remarkable range of poets, artists, playwrights, writers, scholars, critics, journalists, and publishers, and he learns much from them. Going to the theatre, exhibitions, and lectures overlap with almost non-stop wining, dining, dancing, card-playing, and just hanging out with his London pals and associates. He also associates with solicitors, business people, and civil servants. Part of Keats’s intriguing personality is that he is socially at ease—in seeking others and, interestingly, in being sought out—though of course there are moments when he also craves being alone in order to reflect, read, and write. He sometimes needs to get away from London.

Finally, the other myth to sideline is the idea that Keats’s extraordinary poetic

talents are

mainly an inexplicable gift from the muses or the result of overflowing, organic genius.

That’s fine, and about as good as anything to explain whatever it is that Keats’s

and others

like him possess. But often overlooked is how hard and how deliberately Keats studies

literature (and at times art, philosophy, and criticism). When he does so, he often

arrives at

original, penetrating critical insights on how, for example, Milton uses description, how Shakespeare interfuses character and language, and how Wordsworth uses subjectivity to explore

philosophical depth; he even arrives at ideas about what is wrong with the major sonnet

forms.

In short, we might come to a simplified equation: milieu + innate talent + opportunity

+ hard

work = Keats’s progress. (Here, opportunity

in part also represents the fact that Keats

does not have to work while he develops as a poet.) What may, at bottom, be more inexplicable

is Keats’s oft-expressed and genuine desire to pursue the principle of beauty (it

is simply

too easy to say that everything is cultured

). What Keats actually perceives and feels

is not completely rare, but again, his persistent desire to explore and represent

this pursuit

is—and so is his actual poetic execution of this desire in his mature work over such

a very

short time. It is less Nature that cultures Keats; rather, it is more Culture that

cultures

Keats.

*For more on Keats’s medical training, see 15 October 1815.