15 October 1815: Keats’s Continues Medical Training; But a Poet He Will Be—he hopes

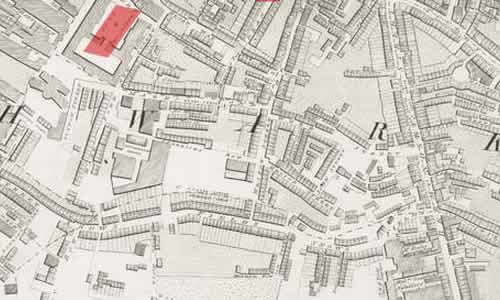

Guy’s Hospital, London

In October 1815, Keats is registered at Guy’s Hospital as a medical student for a year-long course of studies, when he could have just taken an available six-month course. Guy’s at the time is affiliated with St Thomas’ Hospital (they are known as the United Hospitals); between them, they are the leading teaching hospitals in Britain, and they are particularly known for their expertise in surgery and anatomical studies, mainly because of a few of their progressive faculty, while also charitably driven by attempting to serve the poor. There was much experimentation at the hospitals.

By the end of October, Keats is meritoriously selected from a large range of students

as a

dresser

to surgeons (possibly for the next position available), which would have

afforded him a small refund on his tuition. About five months later, by early March

1816,

Keats is officially a dresser, assigned to supervised for a year with a surgeon (in

Keats’s

case, it was with the rather reckless—and somewhat deaf—William Billy

Lucas, Junior).

The end result would work toward credentialing Keats. Testimonials were part of the

review

process.

How did Keats get to this position, to what we might call the second phase of his medical training?

The first phase begins in 1811, when Keats is apprenticed—indentured—for five years to a reputable surgeon, Thomas Hammond, at the fee of 210 guineas (which also included room and board). With Hammond, Keats would have had experience with everything ranging from applying leeches to pulling teeth and delivering babies, along with acquiring general diagnostic knowledge. This arrangement with Hammond is cut short for uncertain reasons, but is possibly related to Keats’s unhappiness with his master; or perhaps, quite the opposite, he is presented with the opportunity to move into higher training via college certification with Hammond’s blessing and support; that is, Hammond would of course have to provide some documentation to attest to Keats’s completion of the apprenticeship. Hammond was himself a student at Guy’s.

Keats’s motives for continuing with this second phase of his training are, then, complex,

beyond the fact that it would have eventually provided him with a decent living. There

is the

personal side: Keats does not like the idea of performing surgery; as Keats tells

his friend

Charles Brown, he was utterly fearful that,

during surgery, he might make a lethal mistake with just one small slip of the lancet

(Brown

records this in his memoir about Keats). Indeed, surgery at the beginning of the nineteenth

century was often brutal, bloody, and chancy, and not for the faint of heart—neither

antiseptic surgical practice nor anesthesiology as yet exist. Despite this, Keats

would have

been very well trained, gaining much practical experience beyond his wide-ranging

lectures by

routinely visiting the wards and assisting, though places like the hectic dissecting

rooms

were gruesome, with the cadavers practiced upon (secured illegally by professional

and well

paid body snatchers—so-called resurrection-men

) not always in the best of shape—maggots

were common to the scene. Nevertheless, Keats’s training and the training facilities

at the

United Hospitals was among the best in Europe, and some of his teachers—like Astley

Cooper and

Henry Cline—also among the leading teachers of anatomy and surgery. Cooper is in fact

later

knighted for his work, and no doubt Cooper’s famous oratorial gifts that combined

passion,

eloquence, and profound subject knowledge struck Keats the poet.

What remains somewhat uncertain, then, is the degree of Keats’s commitment to the

medical

profession, though his efforts (and evidence from some close to him) suggest he was

genuinely

interested in the medical profession. But if surgery puts him off, why might he accept

the

dressership? If he had not shown some strong signs of both skill and dedication, why

would he

have been selected for the much sought-after dressership, and, along with it, the

testing and

increased responsibilities of a duty dresser

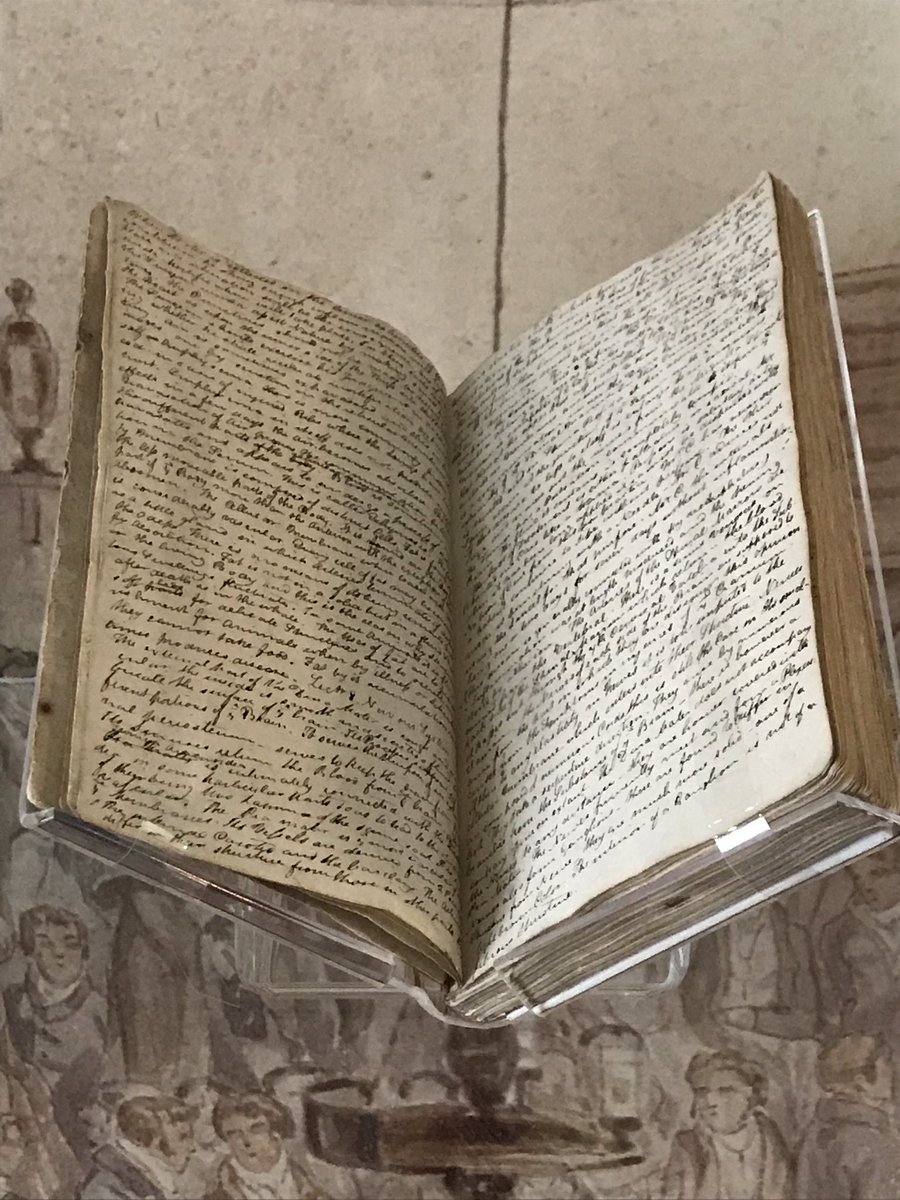

? Nothing suggests that, as a medical

student, Keats was anything but diligent; his medical notebook that survives shows

that he

attended lectures and took fairly good notes, despite the occasional flower doodle

in the

margins. Much later, when Keats seems to have moved beyond his medical career and

fully into

his life as poet, he still holds with him the idea and value of studying medicine

(letter, 3

May 1818, to Reynolds); and as late as March

1819, when on the verge of writing his greatest poetry, he entertains moving to Edinburgh

to

study for a physician

(letter, 3 March, to the George Keates).

Some background: Before 1815, apothecaries were not professionalized or licensed by examination, and there was a fair amount of quackery under the nomination. But in mid 1815, just as Keats finishes his apprenticeship with Hammond and begins training to become an apothecary-surgeon, the Apothecaries’ Act is passed, thus pointing Keats toward a very decent, legitimate livelihood under the umbrella of practical medicine.

Surrounded by other students, and living in the middle of town, Keats no doubt learns

much

about London’s varied inner life in the varied inner city, though in a poem likely

written

during the period—the Petrarchan sonnet To Solitude—he imaginatively transports

himself from the jumbled heap / Of murky buildings

to wax upon the bliss

of

Nature—a Wordsworthian-inspired sentiment, no doubt, and something of a common Romantic

trope.

(We sometimes know the poem as O

Solitude, and it becomes Keats’s first published poem—in Leigh Hunt’s

The Examiner, 5 May 1816.)

Noteworthy: this autumn Keats purchases the two-volume Poems by William Wordsworth, published earlier in the year; it will, however, take a few years for Keats to absorb and, crucially, critically assess the nature and qualities of Wordsworth’s accomplishment. We have to imagine Keats writing poetry while, at the same time, and with conflicted purposes, studying for his medical exams.

By July 1816, aged twenty, Keats completes and passes a fairly involved four-part

medical

exam that qualifies him to practice; permission to even write the exam was reserved

for only a

few. In December 1816, he is officially listed as a certified apothecary. Then, to

the horror

of the family trustee, Richard Abbey, Keats begins

to express his desire to give up medicine for poetry, though Keats, it seems, likely

continues

some work as a surgical dresser into until early March 1817—exactly when his first

volume of

poetry is published—but his decision is then fixed. A poet he will be. Keats was,

at the time

of telling Abbey, fully confident in his calling and potential: I know that I possess

Abilities greater than most Men, and therefore I am determined to gain my Living by

exercising them

(as reported by Keats’s friend, supporter, and publisher, John Taylor, 23 April 1827). This is something of a

remarkable statement for a young, unknown, wanna-be poet; the confidence predicts

an even more

remarkable statement, when, 14 October 1818, he writes, I think I shall be among the

English Poets after my death

(written to his brother and sister-in-law, George and

Georgian Keats).

Falling into and embraced by a kind of progressive literary and artistic circle based around poet, critic, and celebrity journalist Leigh Hunt in late 1816 plays a crucial role in Keats’s poetic aspirations relative to his a medical career.* Thus the year-long course of studies that begins in October 1815 begins to wane exactly a year later when he is introduced to Hunt and, immediately, into Hunt’s wide circle. At various difficult moments in his later life as a poet (translation: having no immediate success as a poet), Keats nevertheless has passing thoughts of returning to the medical profession; and no doubt Keats’s very close encounters with the precarious physicality of medical profession works its way into his views and philosophy, as well as into his poetry. In an age of fairly brutal surgery and haphazard diagnosis, how could Keats not know something of suffering and mortality?

To look for: at least some of Keats’s acquired medical lexicon, his considerable training,

and the varied knowledge associated with medicine in the early 19th-century works

itself into

his poetry. Thus, for example, words like sensation

hold possibly expanded meanings;

likewise, the mystery of the living, creative mind beyond the pure physiology of the

brain and

body no doubt challenges and profitably complicates his own poetics and poetry. And,

obviously, Keats’s front-line medical training (some of it the equivalent of emergency-room

experience) would have had him necessary face human pain, suffering, and frailty in

ways more

direct than almost any other poet. Thus we might, for example, consider more carefully

a

probing passage like this (in an equally probing letter), which ingeniously both links

and

separates the physical and metaphysical mind, while invoking the poetic achievement

of

Wordsworth: I am continually running away from the subject—sure this cannot be exactly the

case with a complex Mind—one that is imaginative and at the same time careful of its

fruits—who would exist partly on sensation [and] partly on thought—to whom it is necessary

that years should bring the Philosophic Mind

(to Benjamin Bailey, 22 Nov 1817). And when we hear poet Keats address mortality and

human suffering, as he does so graphically in the third stanza of Ode to a Nightingale, where he

pictures illness, pain, and suffering as something to both face and escape from, we

might also

picture medical Keats.

So, in terms of Keats’s progress, this period in Keats’s life should give us some pause to consider the complexity of both Keats and his situation. What we do know is that, for the year-and-a-half that Keats is affiliated with Guy’s Hospital—from October 1815 until March 1817—he composes somewhere around forty poems; we also know he is doing well at his medical training; we know that when Keats’s speaks of the mystery of the body, that his medical experience must form at least part of thinking; and, as mentioned, almost in the middle of this period, his social-cultural network explodes via meeting Hunt in October 1816.*

What’s a young, brilliant, good-looking lad to do?

[*See here for a mapping of Keats’s social network and Hunt’s place in it.]