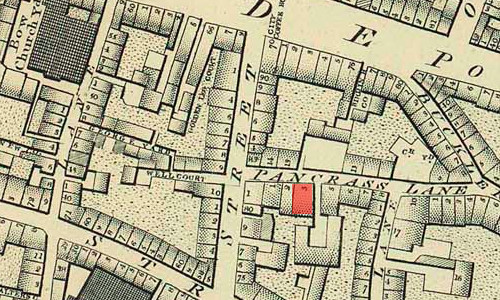

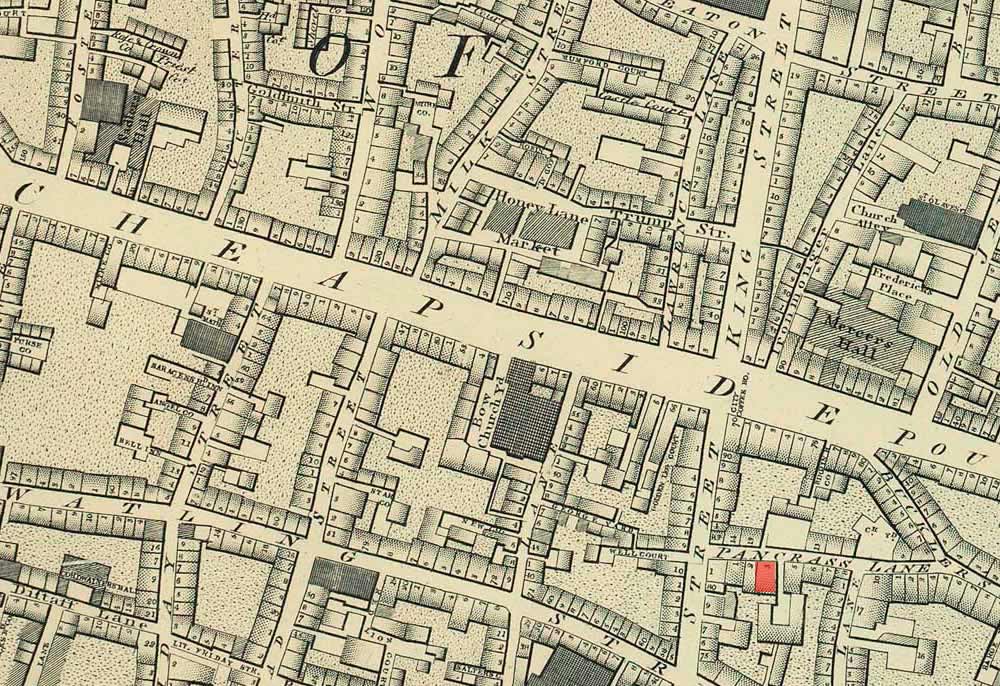

1810 & Later: Richard Abbey, Keats’s Guardian & Trustee

4 Pancras Lane (The Poultry), London

The offices of Richard Abbey (a tea

merchant/broker [Tea-Dealer

]), who, as primary guardian and trustee of the Keats

children after the deaths of their mother, Frances in 1810, and his maternal grandmother, Alice Jennings, in 1814, oversees the relatively significant

family inheritance—and not always, it sometimes seems, transparently. Abbey lives

part-time on

the premises at Pancras Lane. Keats’s younger brothers, George and Tom, for a spell work for

Abbey as clerks. The other guardian appointed by Alice is John Nowland Sandall, who

dies in

1816, leaving Abbey in solely in charge of the family money.

Keats will have continuing problems in securing predictable funds from this family inheritance, though this in part is due to Keats attempting to live on credit based on the capital of his inheritance money. Four problems: 1) Keats does not seem to budget very well with the piecemeal doling out of family money from Abbey, and he tends to overspend after he leaves his medical training; 2) he makes loans to friends based on his credit, and he borrows, too; 3) Abbey, who seems to have been an untrusting or at least sceptical sort when it came to Keats, often seems to keep Keats uniformed about the admittedly complex family resources; and 4) no one, including Abbey, is aware of a fairly decent sum of family money held by the courts (perhaps Abbey might have been more diligent in understanding the fullness of the family money).

It seems Abbey also takes some trouble to keep Keats away from his younger sister, Fanny, which greatly upsets Keats. Keats comes to feel a little guilty that he never sees enough of her. To the end of his life, Keats does not like or trust Abbey, though one of Keats’s brothers, George, is well disposed toward Abbey. But lest we forget: the trickling of family money that comes to Keats does, for a number of years, allow him to pursue his life as poet without the necessity of any gainful employment; his family legacy, in effect, becomes our own.

Abbey takes Keats out of Enfield school in summer 1811, and he then uses a fair share of Keats’s family money to sponsor Keats’s medical training as a five-year apprentice to Dr. Thomas Hammond in Edmonton, for the fee of 200 guineas. Abbey becomes unhappy with Keats’s lack of enthusiasm for the medical profession, though it appears Keats does quite well in his training. When Keats announces his literary goals, Abbey feels that Keats’s poetic ambitions are absurd. We have to picture why Abbey and Keats are mutually distrustful: Abbey is a well established businessman with strong, like-minded connections within his community; Keats, on the other hand, wants to be a cool poet, and he comes to have connections with mainly dissenting, liberal, and artsy types.

After Keats’s death, Abbey becomes a relatively important source of information about Keats’s family and life, although his views are sometimes considered unreliable and tainted by his own interests and values—by his own narrative, that is.