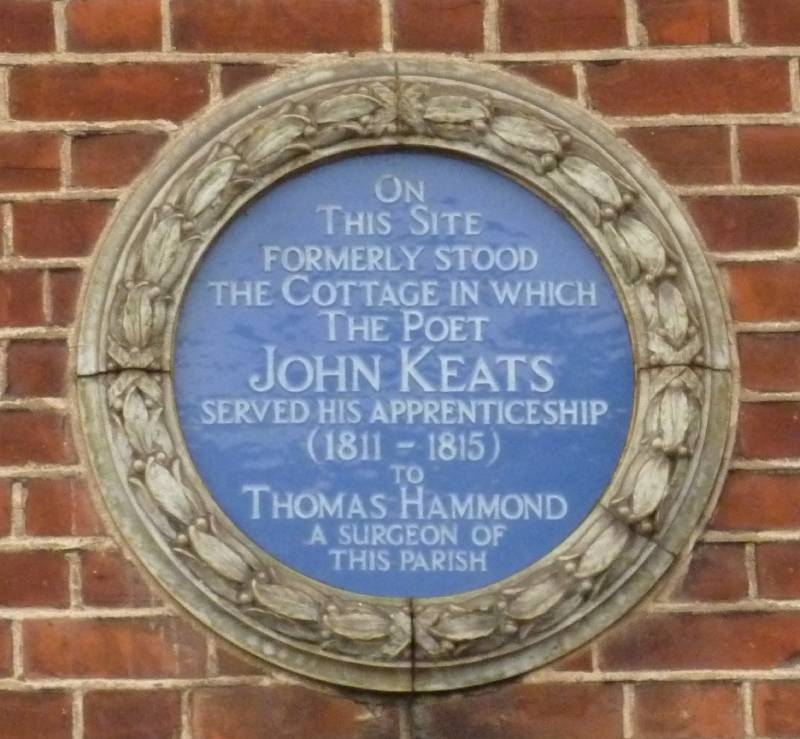

1811-1815: Medical Apprenticeship & Charles Cowden Clarke

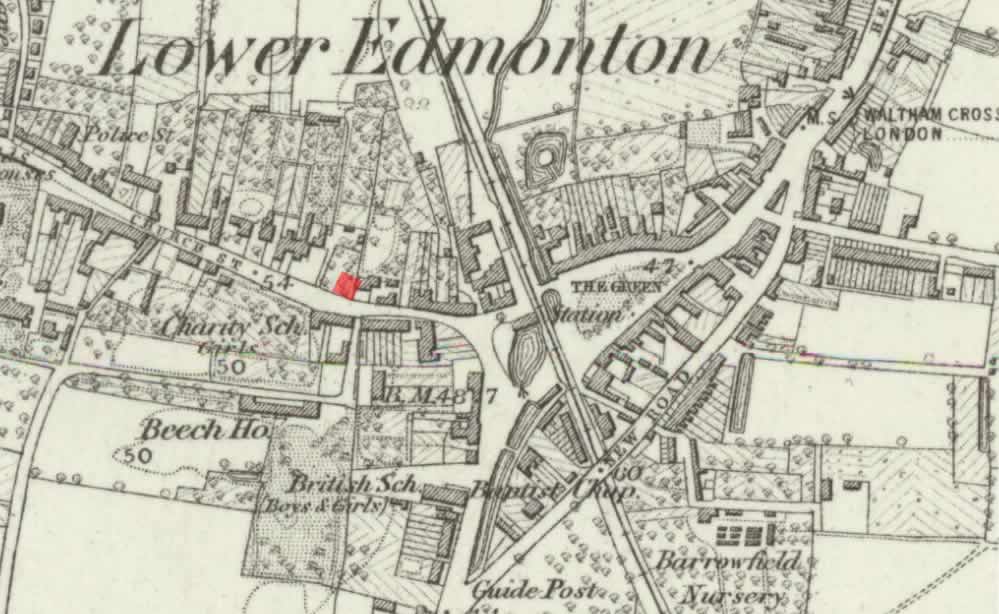

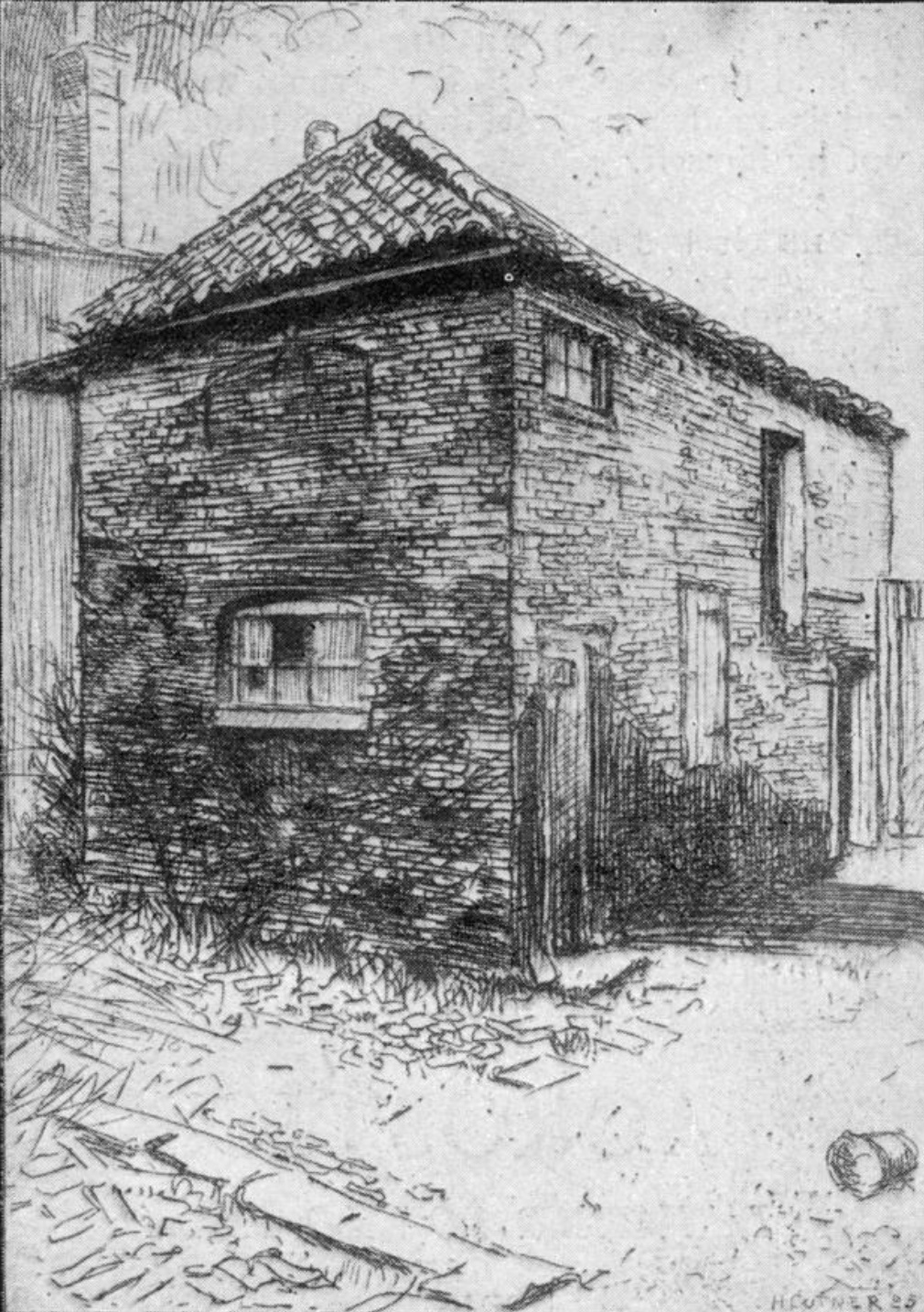

7 Church Street, Edmonton 1811-1815

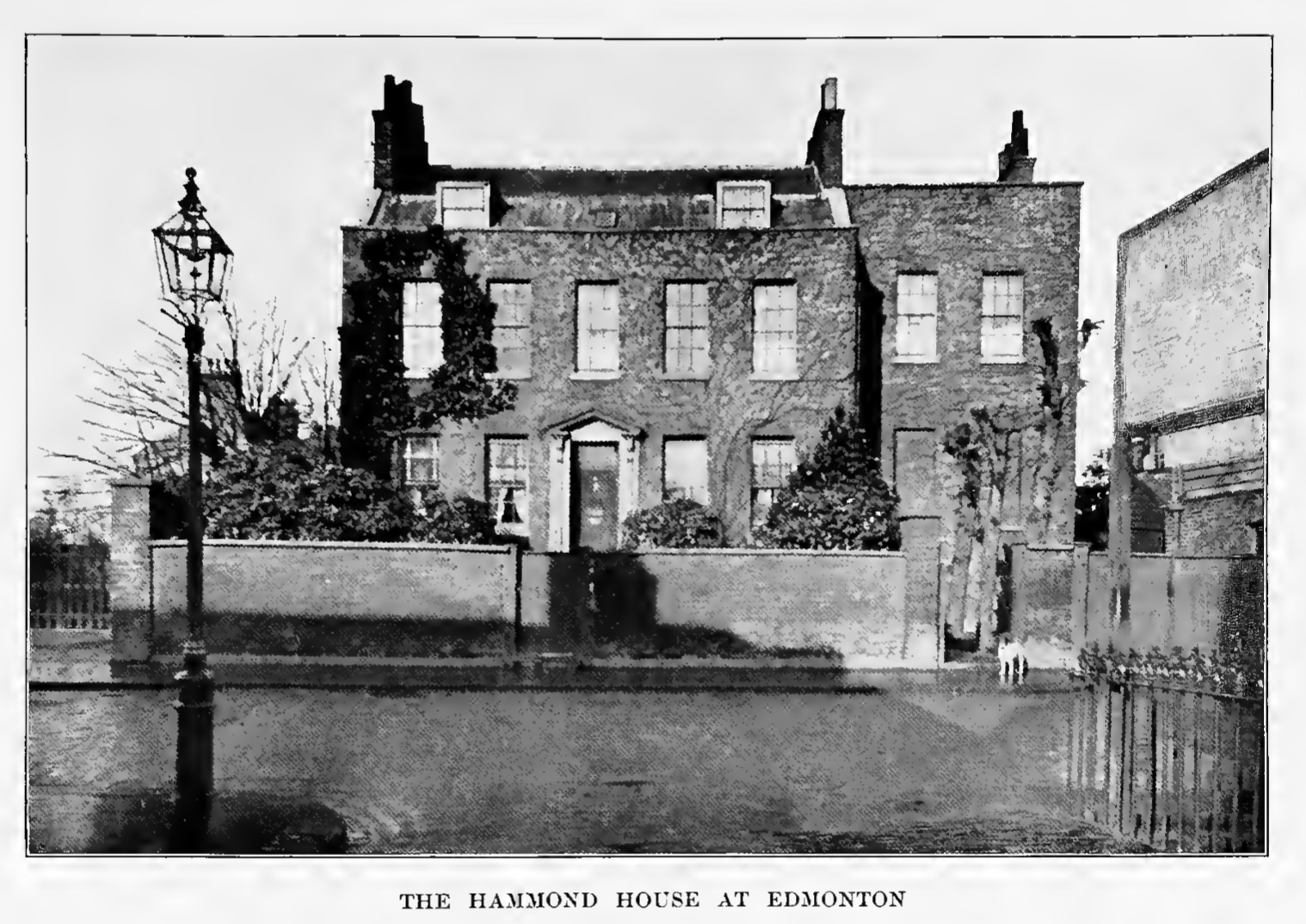

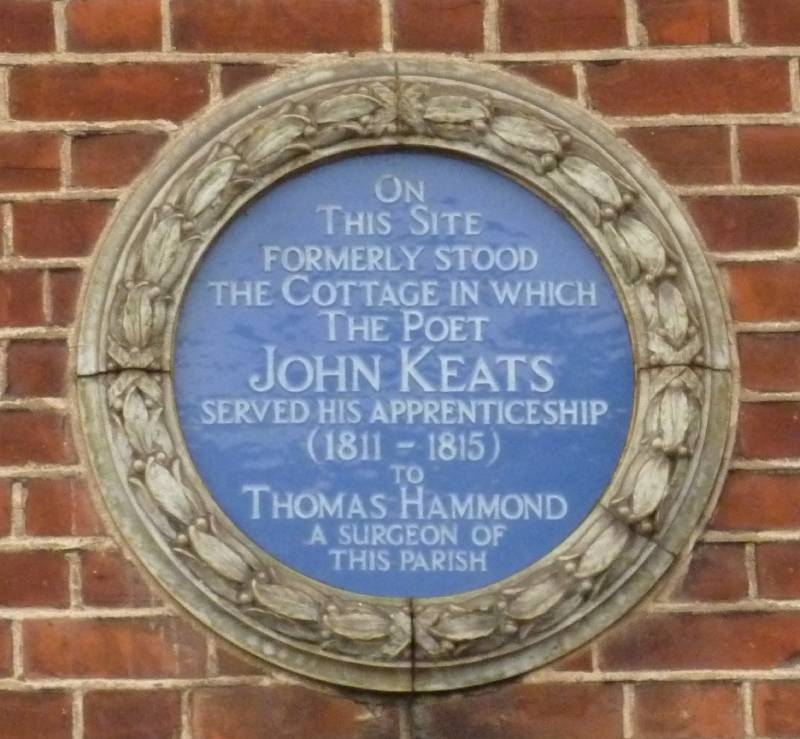

From 1811 until 1815, and after leaving Clarke’s Academy in Enfield, Keats apprentices (is indentured) as a surgeon/apothecary to the experienced and well-connected Thomas Hammond, who lives at 7 Church Street, Lower Edmonton.

Hammond is actually a family friend, and so the fit with Keats seems good. The apprenticeship is quite expensive, and family money (likely from the sale of stocks) is called upon. A medical practice continued at this address into the 20th century; the building was destroyed and replaced by shops in the 1930s.

As an apprentice, there is a certain amount of unpleasant work, though Keats has spare time for other pursuits. Keats and Hammond at moments may have had a clash of personalities. Keats later recalls clenching his fist at Hammond (letters, 21 Sept 1819), which, in recollection, may be a more symbolic gesture than an actual one. In any case, the apprenticeship seems not to have gone perfectly, but it was a time of relative stability for the at-times emotionally unsteady Keats, who comes to experience short periods of anxiety and moderate bouts of depression.

By about mid-1814, Keats, aged 18, shows signs of taking poetry reasonably seriously,

though

(as far as we know) his output does not expand greatly until the second half of 1816.

Perhaps

justifiably, given his age and experience, many of these early poems, either implicitly

or

explicitly, are about fame and Keats’s desire to be a poet. Just as often, and equally

justifiably, Keats betrays doubts about his poetic worthiness, and so poets ranging

from Homer, Tasso, and Spenser to Chatterton and Byron are invoked and explored as inspirational models;

these are the stars upon which the novice poet gazes. (With the war with France winding

down,

Keats also attempts some lines of political and historical relevance, but these are

mainly

passing concerns.) Rather than his early medical training, then, this young poet writing

about

becoming a poet constitutes the other half of his apprenticeship. Keats’s extraordinary

mastering

of poetry will take about four years, though the subject of his own poetic

worthiness and enduring fame takes more than half of that time to fade away; at the

same time,

his letters to various friends and his family reveal his thinking about and commitment

to

poetry.

While a medical apprentice, Keats’s poetic progress is significantly, perhaps even

decidedly,

influenced and encouraged by Charles Cowden

Clarke, the son of his old headmaster at Enfield school, and eight years Keats’s

senior. For a while, Keats and Clarke have weekly get-togethers. Books and literature

seem to

bond the two, and Keats begins to assume some of Clarke’s tastes—the poetry of Spenser becomes especially influential, with Milton also being studied, though at this point Keats

does not quite get

Milton (a few years later he will, and he declares Paradise Lost a wonder). Clarke was also seriously interested in

theatre and music (and possessed a decent tenor voice).

Keats celebrates Clarke’s guidance in the

epistolary To C. C.

Clarke (Sept 1816). While the poem thoughtfully thanks Clarke for showing him

the sweets of song

(53), Keats openly reveals insecurities about his own ventures

into rhymes and measures

(98). Characteristic of this phase in his poetic development,

Keats sprinkles classical references over the poem, as if to give it some classical

cachet—credibility, that is. The poem is published in Keats’s first collection, the

1817 Poems.

But it is really in October 1816, when Clarke introduces Keats to poet, critic, and celebrity journalist Leigh Hunt, that Keats’s world hugely changes and expands.** Keats’s idea to become a full-time poet becomes set. Earlier, in May 1816, Hunt is also the first to put Keats in print by publishing O Solitude, in Hunt’s journal The Examiner. Meeting Hunt immediately places Keats into a particular network (generally what we today we might call the liberal-left) of artists, writers, journalists, publishers, and other poets revolving around London, most of whom very quickly believe in and support Keats’s poetic aspirations. Connecting Keats with Hunt also marks the dissipation of the close relationship between Clarke and Keats. Keats now has new mentors who expand and challenge his tastes, desires, and literary values.

Given that Keats’s father dies in 1805 and his mother in 1810, we might want to see Clarke as a kind of temporary parent or even father figure; however, surrogate big brother might be closer to capturing his role. At the very least, he is a guiding, encouraging literary influence through Keats’s later teens.

Eventually, Clarke takes up book-selling and music publishing. He later gives lectures on literature (which earn him a some reputation); and, most significantly, he produces important scholarly work on Shakespeare.

Clarke’s remembrances are probably the prime source of direct information we have about early Keats. Without Clarke, Keats’s path might have been different. His Recollections of Keats (1861) recalls young Keats as determined and orderly—a young scholar with growing, ravenous reading habits; yet Clarke troubles to note that Keats was both passionate and, when called upon, pugnacious; he also recalls Keats as singularly high-minded and generous, and genuinely liked by all.

With or without difficulties with Hammond, and despite his growing dedication to poetry, Keats will continue his medical training by registering as a surgical student at Guy’s Hospital (London) on 1 October 1815, and very soon he is soon in line for a dressership (a kind of assistant surgeon)—which, in fact, is something of a distinction. He later passes the apothecary exam in July 1816, giving him the certification of Licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries. In short, it appears Keats is (or became) genuinely interested in the medical profession, learned a great deal, and even excelled, but, as his friend Charles Brown reports, Keats had fears that (at least in performing surgery) he might do harm. [For more on Keats’s medical training, see 15 October 1815.]

*My sincere thanks to Annette Sparrowhawk of the Enfield Local Studies Library & Archive for these images of 7 Church Street and further information about Hammond’s surgery.

**See here for the importance of Clarke as the key hub in Keats’s emerging social network.