18 December 1795: Keats is Baptized; Keats and his Religion

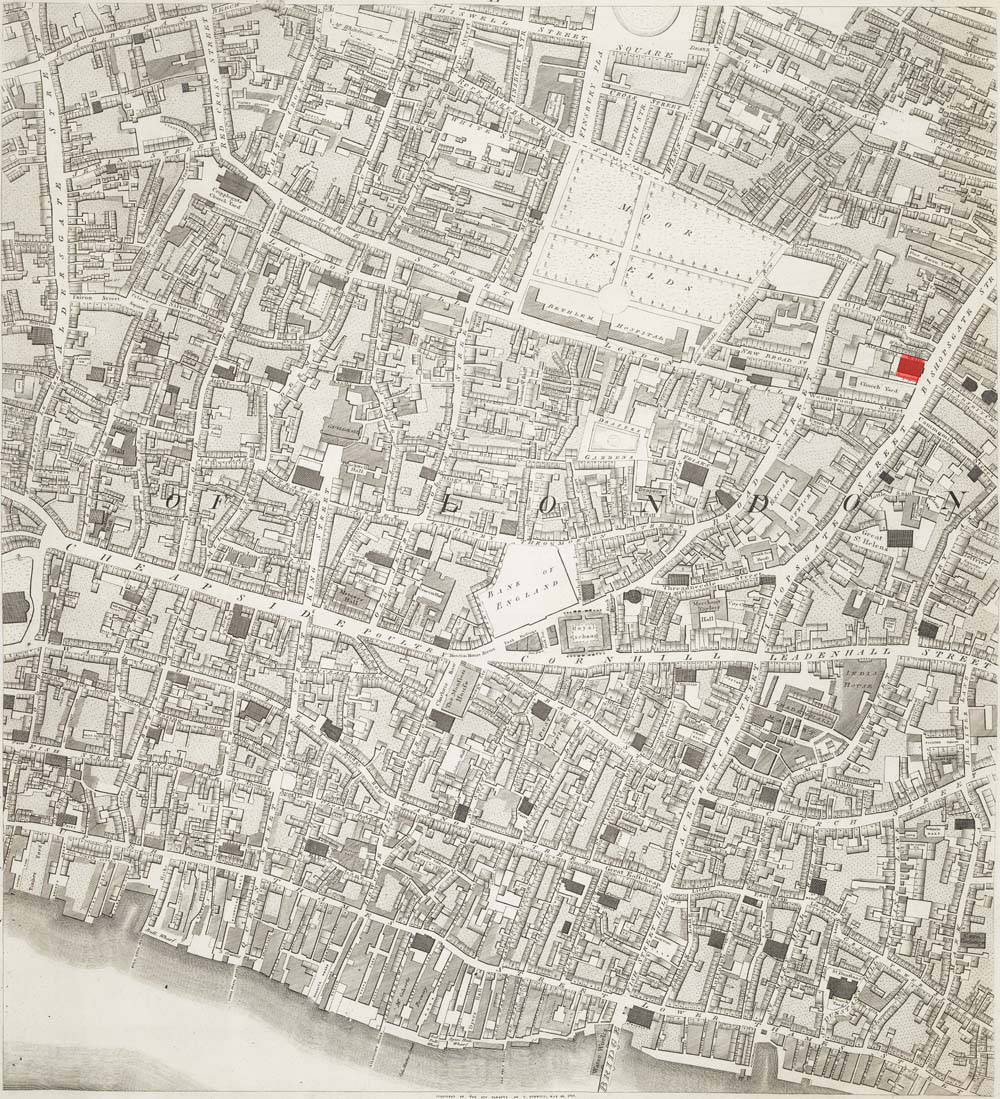

St. Botolph’s Church, Bishopsgate, London

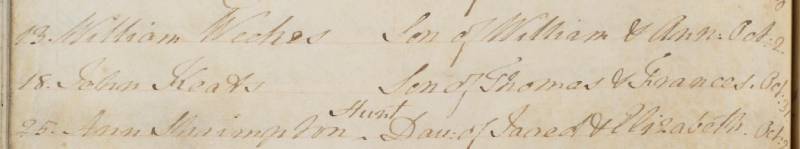

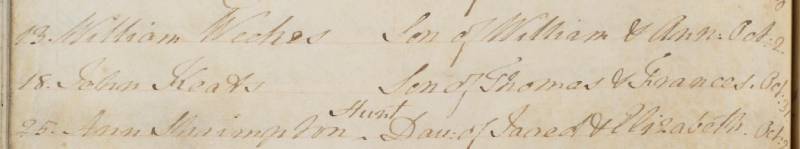

St Botolph-without-Bishopsgate: Where Keats is baptized, 18 December 1795; his sister, Fanny, is also baptized there, 17 June 1803.

It appears the Keats’s maternal family-of-origin were not strongly connected to mainstream, organized religion; if anything, they held dissenting sympathies. Keats’s personal views about conventional Christianity hedged toward viewing it as misguided superstition at best and purely fraudulent at worst. This does not stop Keats from employing religious imagery or a religious lexicon in his some of his poetry; after all, such language—carried by words like soul, divine, holy, heaven, sacred, spirit, faith, joy, and rejoice—is a pervasive and naturalized part of his cultural legacy, and, when used, carry potent, suggestive resonance. What notions Keats did hold about the soul and the afterlife were hardly in accordance with prevailing, doctrinal teachings. Keats might be said to be religious (inasmuch as he entertains ideas about the deep mystery of life and some version of an afterlife), but at the same time, his strong skeptical nature turns him toward seeing religion a form of myth-making.

For Keats, the very human, sensual realm is the domain of divination, and, in the end, as he privileges the imagination rather than faith as a way of knowing and truth-seeking, he sees poetry as a means to engage and represent this experience. In short, for Keats, the higher reality is already here, within the realm of the human and in what he called earthly things; human suffering is not some consolation for intimating the everlasting, but part of the measure through which we profoundly experience the meaning of human life. When Keats for moments moves beyond his deep scepticism, he turns to the idea that devotion and sacrifice is to be connected to a principle of beauty, which, paradoxically, springs from passing human consciousness into eternity. In the end, his poetic progress will be an attempt to create such ever-enduring forms. Thus, for example, he will poetically construct eternities from a stilled yet moving season, a fading nightingale’s song, a beautiful but unknowable urn, the feeling of unresolved love, and moments caught between warm dreams and cold reality.

From baptism to death: As Keats knowingly approaches his end, with his body uttertly

racked

by tuberculosis, he writes to closest friend, Charles

Brown: Is there another Life? Shall I awake and find all this a dream. There must

be[.] We cannot be created for this kind of suffering

(30 Sept 1820).