8 October 1818: Endymion Attacked, Poetics Predict Progress, & Woodhouse’s Prediction of Greatness

The Morning Chronicle, 332 The Strand, London

John Wilson Croker’s nasty attack on Keats’s

long poem Endymion in The Quarterly Review is itself attacked by

J. S.

(the writer and editor, John Scott,

likely) in a letter to The Morning Chronicle. A few days

later, on 6 October, Keats’s friend and fellow poet/critic, John Hamilton Reynolds, defends Endymion in another journal, and he calls out The

Quarterly Review for victimizing Keats simply because of his youth. Less than a week

later, Leigh Hunt, another of Keats’s supporters

and friends, reprints the defense in The Examiner (11 Oct).

The terms of reference for the attacks on Keats are motivated at least as much by

class and

politics as by poetical tastes. Keats’s connection to the liberal-reformist camp centered

in

London (and often revolving around Hunt) makes him an easy target for the conservative

guns;

and, in truth, so does the mainly ineffectual character of his early poetry. It may

seem an

exaggerated or inappropriate metaphor to say conservative guns,

but Scott will be

killed in a pistol duel over what some Tory journals say about Hunt and Keats [see

16 February 1821 for more about the duel].

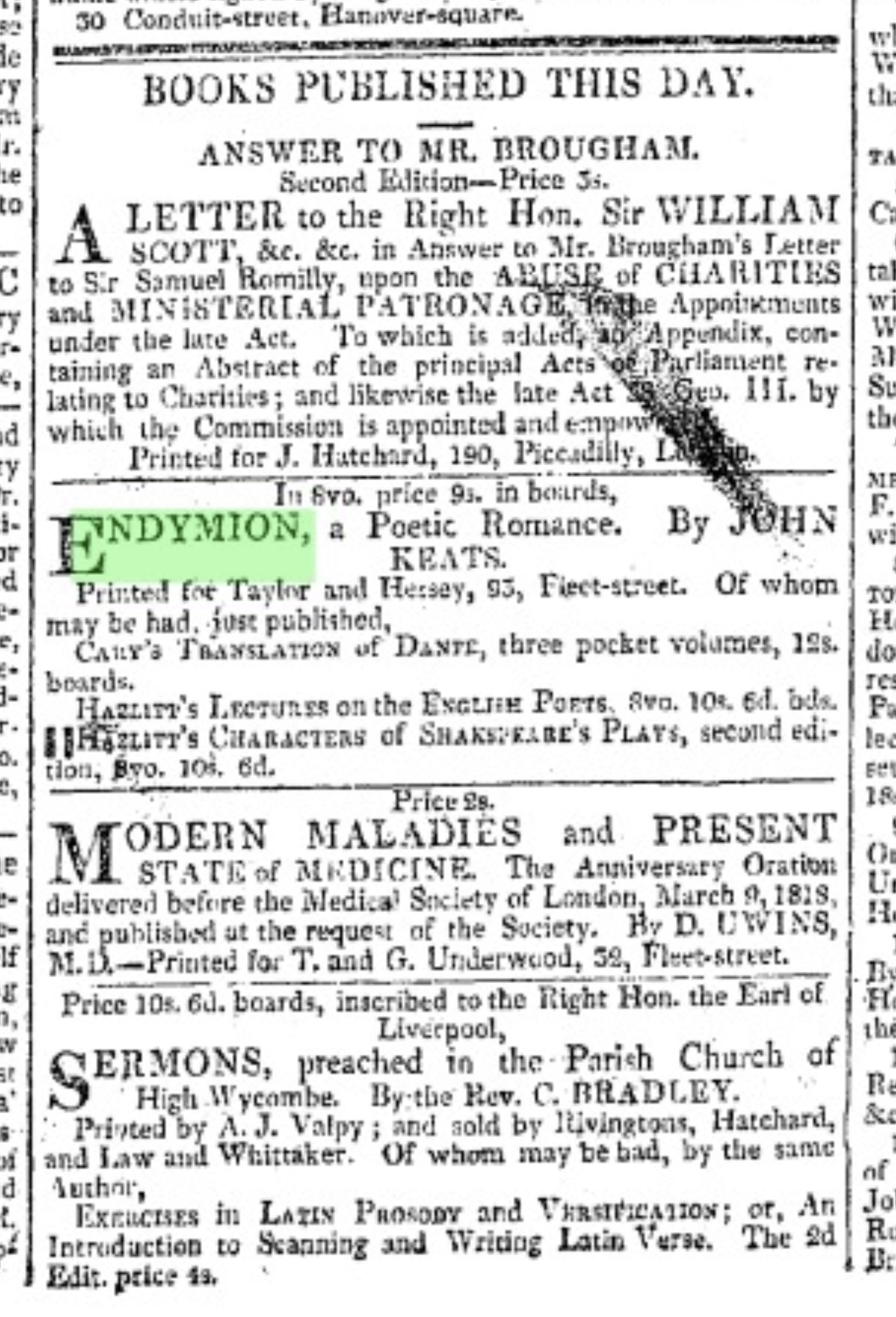

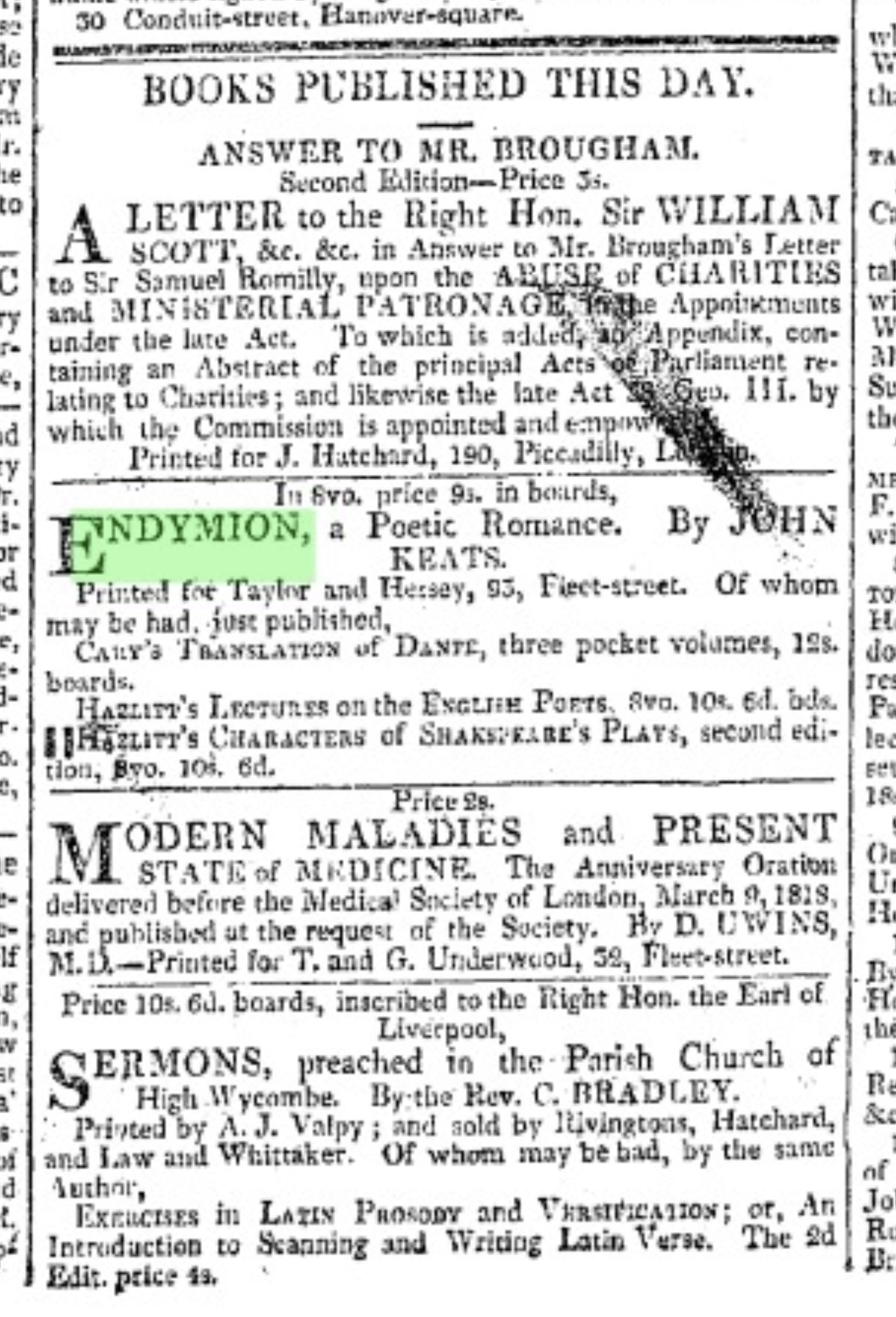

Endymionadvertised in The Morning Chronicle, 13 October 1818. Click to enlarge.

Today we might term the attack on Keats ideological. But these tensions are part of Regency Britain’s larger culture wars: emerging new ideas of class begin to counter old ideas of rank, with old money being challenged by mercantile capital and the vagaries of a market-driven economy, and with conservatism challenged by reform. And Keats’s poetry can, in a way, with its more excessive style and unconstrained form—manifest, in the case of Endymion, by enjambed, liberating couplets, as opposed to end-stopped, neoclassical couplets—sound a challenge to conservative tastes, and therefore values.

The Morning Chronicle is itself a clear challenge to the

dominant Tory papers, and more generally reflects the rise of anti-government sentiment;

and

with struggling foreign trade issues, weaving and lace industry violence not fully

under

control, and with distrust of the government with its domestic spies, the possibilities

for

radical action were very real. Britain, at this time, then, feels the tensions and

rumblings

of social change, with the rise of the as-yet unnamed working-class beginning to assert

itself

more openly. Keats, given his poetic interests, and not nearly so driven by politics

as his

direct contemporary and acquaintance Percy

Shelley, would not write a poem to assert the rise and persecution of this new class

and social injustice, but Shelley could, and in September 1819 (writing as an expatriate

from

Italy, and stunned by the so-called Peterloo Massacre in Manchester in August) he

composes

such a poem, containing the determined refrain, Ye are many—they are few.

Shelley’s

ballad is called The Mask

of Anarchy; it remains perhaps the greatest poem of protest and

resistance in the English canon to stand against class inequality; its volatile nature

prevents immediate publication; it does not see print until 1832, a decade after Shelley

drowns—with a copy of Keats’s 1820 collection of poems found crammed into his pocket.

[For

more about Shelley’s drowning, go to 12 August 1820.]

Keats in October writes he has become a little acquainted

with his own strengths

and weaknesses,

which suggests signs of poetic maturation. As far as those churlish

reviews of Endymion go, Keats remarks that they are only a

momentary effect on the man whose love of beauty in the abstract makes him a severe

critic of his own Works.

His self-criticism—domestic criticism

—is harsher than

anything others might dole out. He realizes Endymion is,

overall, slack, imperfect, and perhaps even a failure,

yet necessary for his own

development and poetic independence. Had he stayed upon the green shore, and piped a silly

pipe, and took tea & comfortable advice,

he would not have learned a thing—this

seems to be a swipe at Hunt’s suburban school of

sociable poetry, from which he is determined to move away (letters, 8 Oct 1818).

By the end of October, in an important exchange with his friend and advisor to his

publishers, Richard Woodhouse, Keats’s poetics

take a further and crucial leap: he distinguishes his poetical character from the

wordsworthian or egotistical sublime.

He praises the camelion Poet,

one who is

without identity because its character enjoys light and shade; it lives in gusto, be it

foul or fair, high or low, rich or poor, mean or elevated.

The poet fills what ever body

it is in for.

As a result, the Poet is the most unpoetical of any thing in

existence

(letters, 27 Oct 1818). Although some of this language and attitude derives

from the ideas of his friend, the essayist and critic William Hazlitt (mainly in Hazlitt’s views about Shakespeare in his lectures on the English poets, as well as in

his essay On Poetry in General), Keats makes these ideas his

own, and with clear passion and determination. He will be that camelion poet who lives

within

its subject.

Keats’s final burst of poetry, beginning within months, enacts these poetics. He will attempt to compose poetry that gives in to neither temperament nor sentiment; and he will do so mainly in a lyric mode, one that, with remarkable composure, will explore how thought, feeling, and sensation are intertwined. The human condition—one that faces and negotiates suffering, death, and immortality with imaginatively sympathetic capabilities—becomes the poetic condition when manifest in a perfectly complementary and unobtrusive form. This is perhaps the apogee of what great art achieves—and it marks Keats’s most enduring work.

Also noteworthy are Woodhouse’s comments

about Keats, made 23 October, to his cousin, Mary Frogley, since they express the

very high

regard Keats’s friends hold for him. Woodhouse believes that Keats’s poetical merits,

his original genius

and brilliancy,

have not appeared since Shakespeare and Milton. Keats’s work does display some of the faults

of his relative

youth,

but Woodhouse predicts that Keats will rank on a level with the best of the

last or of the present generation; and after his death will take his place at their

head—.

This is a remarkable prediction—more remarkable in that it becomes true.

At this point, Keats’s youngest brother, Tom,

whom Keats is nursing, is becoming increasingly weakened with consumption. At the

beginning of

the month, Keats (not for the first time) is reading King Lear,

and at one point he underlines a phrase that appears half a dozen times in Act 3,

Scene 4:

poor Tom.

Keats has much to face. Poor Tom, indeed; and poor Keats.