14-31 October 1818: Caring for Tom, his Poetical Character, & Being Among the English Poets

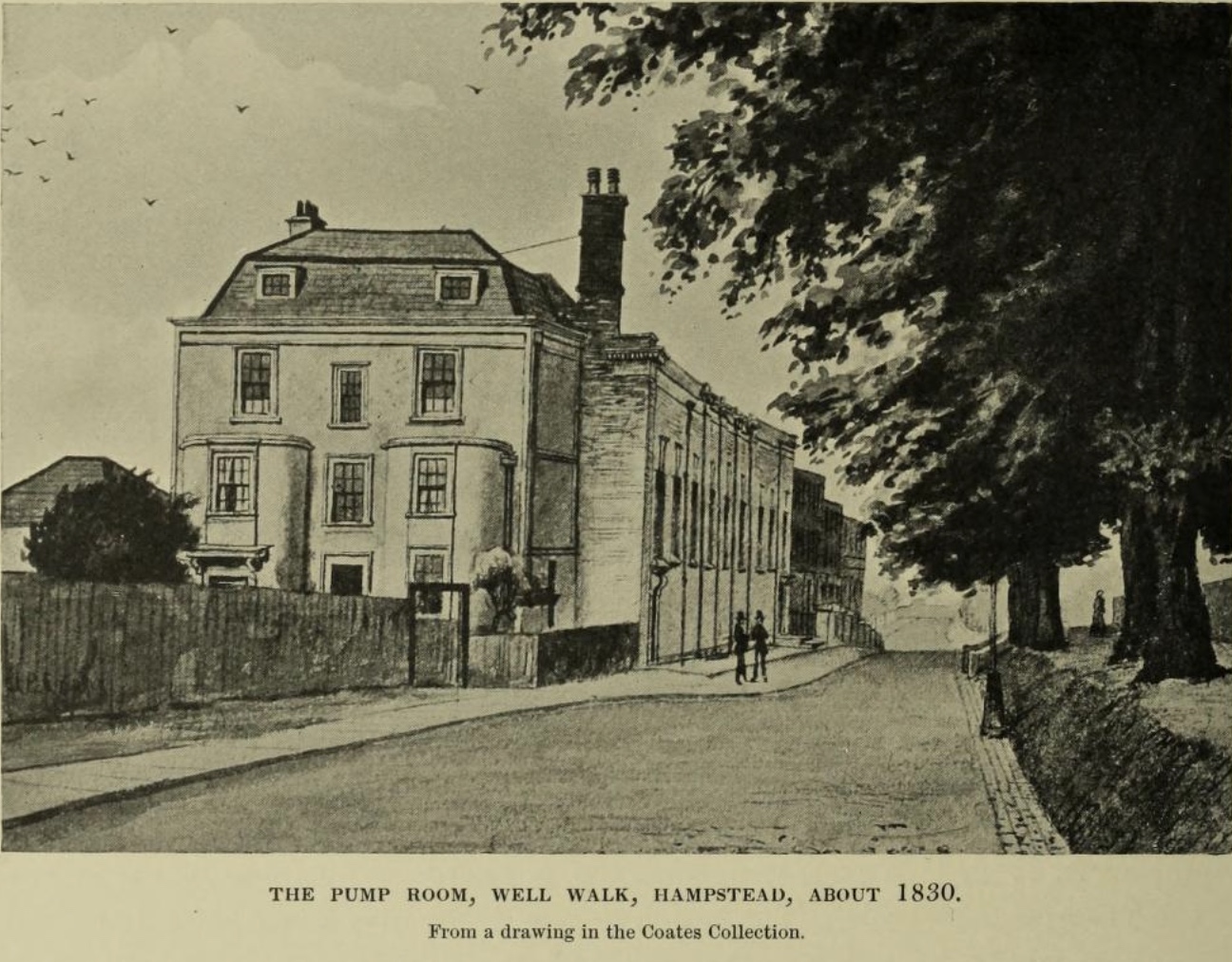

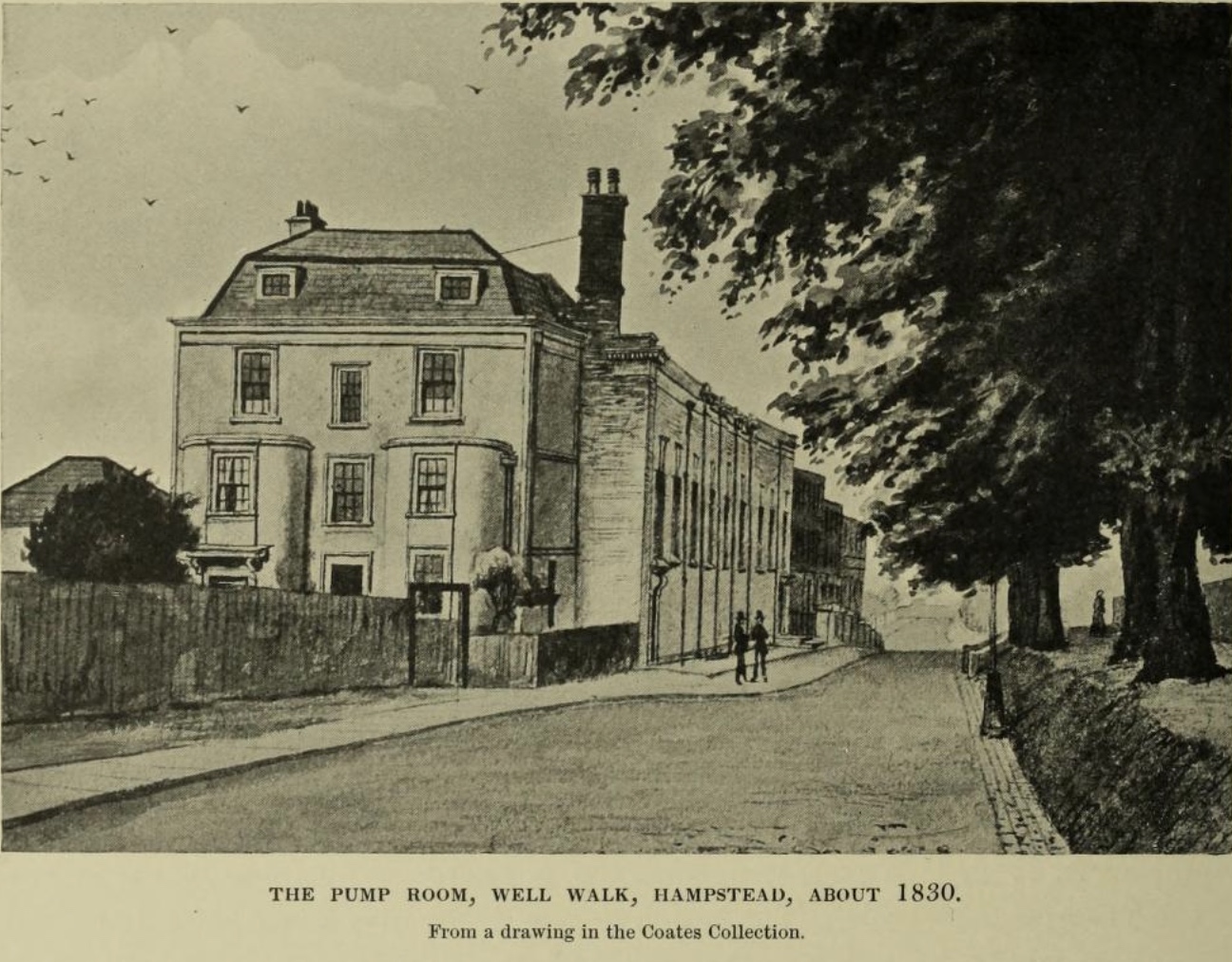

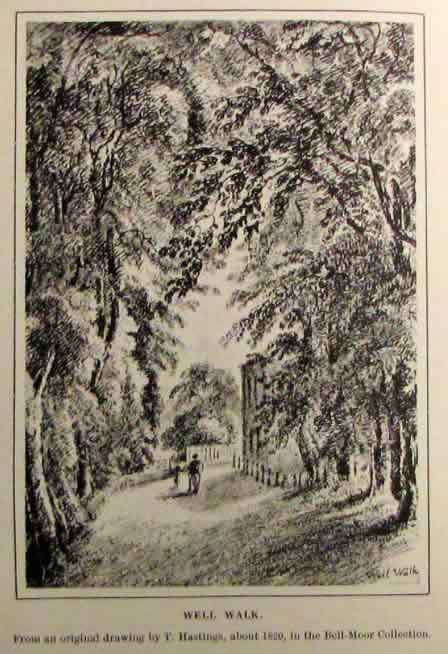

1 Well Walk, Hampstead (now No. 46)

Where Keats lives, and from where Keats sends a long letter to his brother, George, and sister-in-law, Georgiana, who emigrate to America in June 1818. They are, like tens of thousand of others from Britain in the first half of the 19th century, looking for new opportunities, mainly in employment and in the acquisition of land—and a new politics.

From mid-August until early December, Keats’s physical and emotional life is taken

up with

the day-to-day care of his other younger brother, poor Tom

(letters, 14 Oct), whose

ever-weakening health weighs heavily upon Keats. Taking care of Tom, Keats admits, is Misery

(letters, 16 Oct).

Tom’s agonizing slide toward death by

consumption sets many things in perspective for Keats, including a renewed focus on

his poetic

ambitions (and understanding his own strength and weakness

—letters, 8 Oct), as well as

lingering fears about his own health. Yet, remarkably, Keats states that the only

thing that

can ever affect me personally [. . .] is any doubt about my powers for poetry—I seldom

have

any, and I look with hope to the nighing time when I shall have none

(letters, 24 Oct).

Keats does make an even more remarkable statement this month in a letter to the George Keatses: I think I shall be among the

English Poets after my death

(letters, 14 Oct). In fact, in the early months of 1819, he

will have some doubt about this hope, yet, as we see, his somewhat plucky prediction

becomes

fact. Keats is generally ranked as being among the best or most important poets in

the English

canon.

In a continuation of his poetics, Keats articulates what kind of poetry he wants to

produce—and, very significantly, what kind of poet he needs to be. He expresses his

desire to

write poetry channeled through and governed by selfless, imaginative empathy, by emotional

depths and necessary contraries, and by independent values and beliefs. By the end

of the

month, writing to Richard Woodhouse on 27

October, he memorably and at length describes his own Poetical character

(as

differentiated from the wordsworthian or egotistical sublime

):

[I]t is not itself - it has no self - it is every thing and nothing - It has no character

- it enjoys light and shade; it lives in gusto, be it foul or fair, high or low, rich

or

poor, mean or elevated - It has as much delight in conceiving an Iago as an Imogen.

What

shocks the virtuous philosopher, delights the camelion Poet. It does no harm from

its relish

of the dark side of things any more than from its taste for the bright one; because

they

both end in speculation. A Poet is the most unpoetical of any thing in existence;

because he

has no Identity - he is continually in for - and filling some other Body - The Sun,

the

Moon, the Sea and Men and Women who are creatures of impulse are poetical and have

about

them an unchangeable attribute - the poet has none; no identity - he is certainly

the most

unpoetical of all God’s Creatures. If then he has no self, and if I am a Poet, where

is the

Wonder that I should say I would write no more? Might I not at that very instant have

been

cogitating on the Characters of Saturn and Ops? It is a wretched thing to confess;

but is a

very fact that not one word I ever utter can be taken for granted as an opinion growing

out

of my identical nature - how can it, when I have no nature?

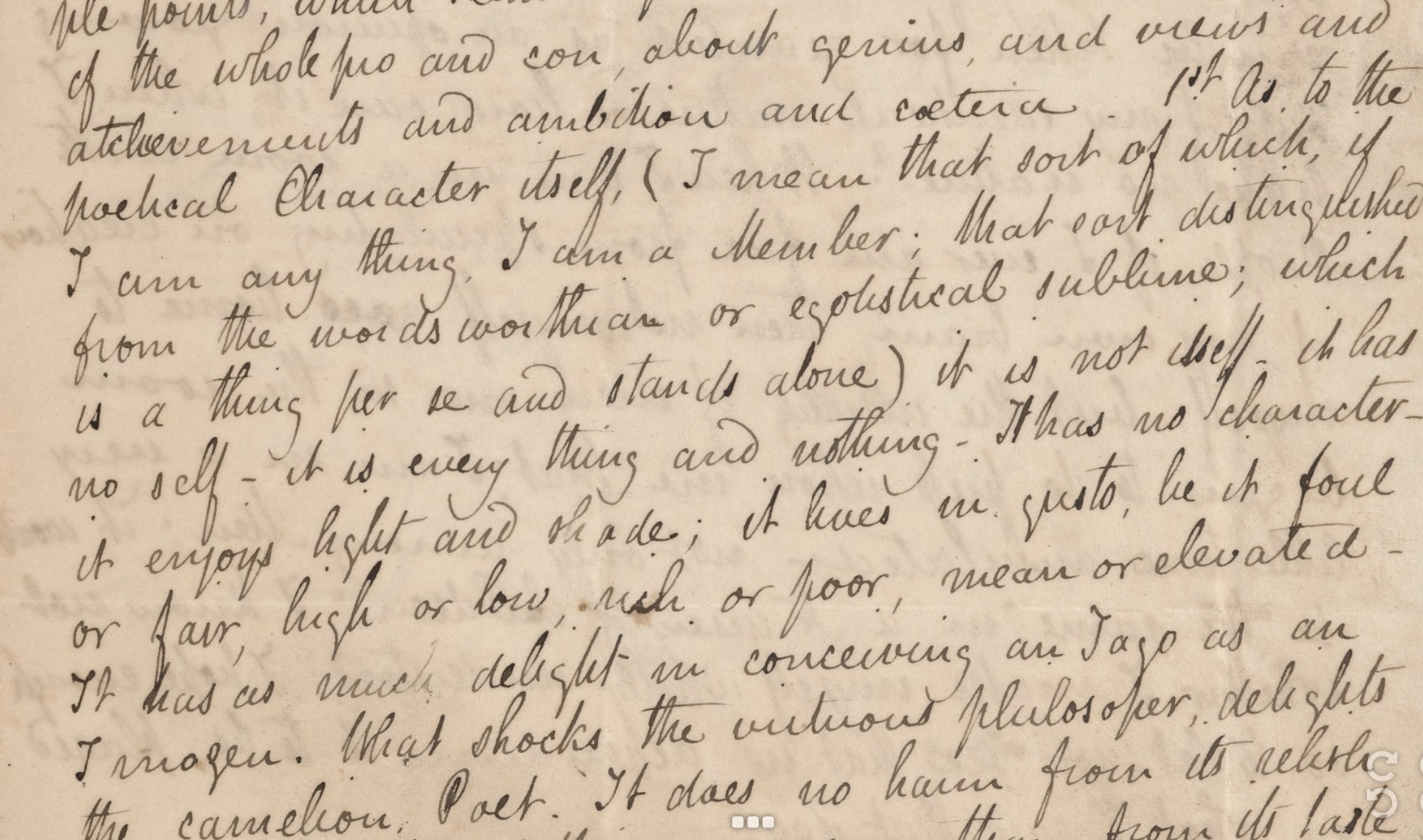

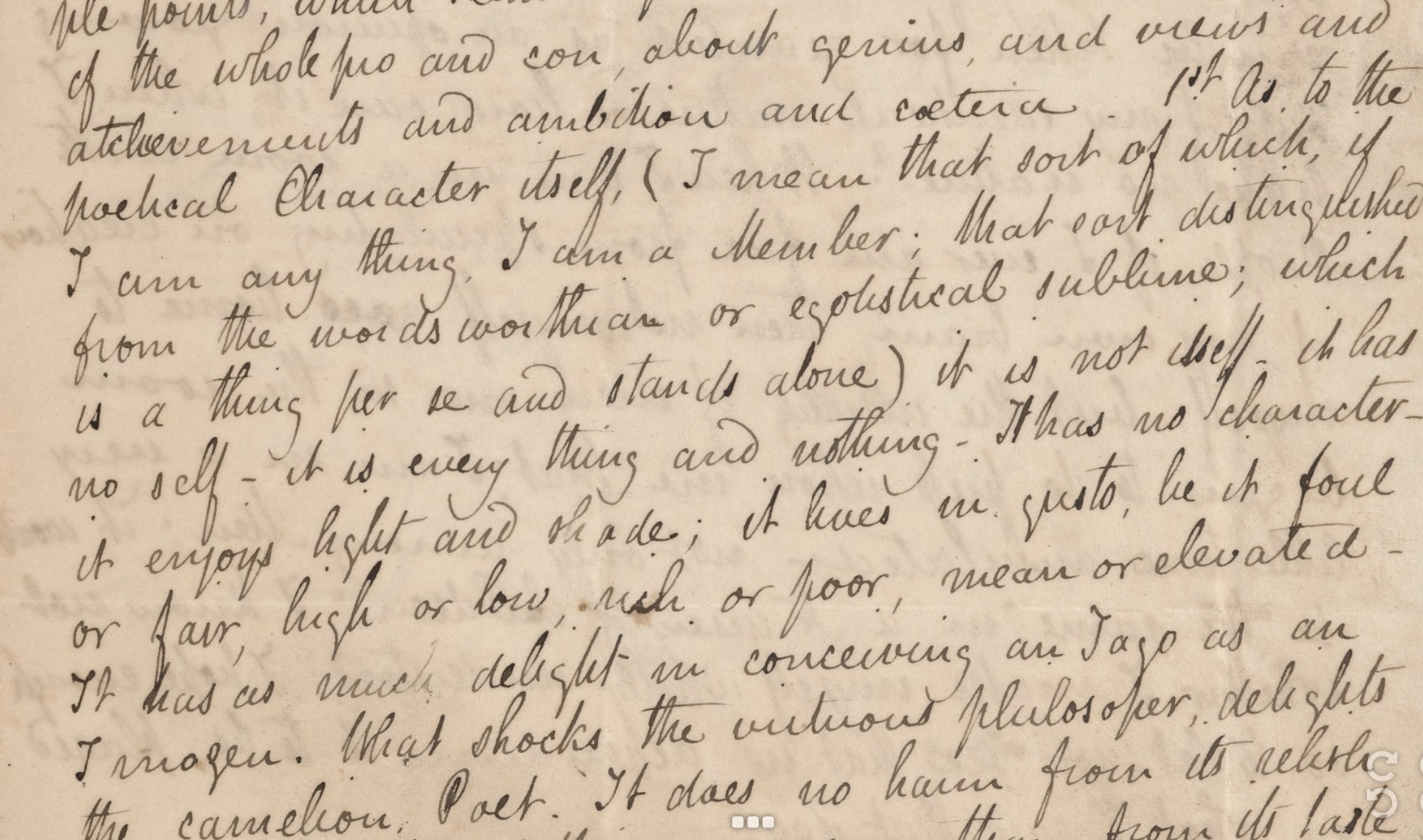

As to the poetical Character itself . . . the camelion Poet.MS Keats 1.38, John Keats Collection, Harvard Library. Click to enlarge.

Keats adds a bottom line about his poetic aspirations: I will assay to reach to as high a

summit in Poetry as the nerve bestowed upon me will suffer. The faint conceptions

I have of

Poems to come brings the blood frequently into my forehead.

This is the picture of not

just a motivated and extraordinarily striving poet, but one who is delibe_rately defining

what

kind of poet he has become—and as a result, what kind of poetry he will write.

We see, then, how Keats moves from and beyond occasional circumstances, immature poetic ambitions, ill-defined poetic projects, affected and incidental description, as well as the sociable need to entertain and the public demands to conform. Upon and out of these complex principles of poetic (non)identity, by the end of this period of caring for his brother, who passes away on 1 December, Keats will, within less than a year, produce some of the most striking poetry in the English canon—until, that is, his own deteriorating health levels his progress.

Understandably, though, at this point, for Keats writing poetry also represents the

practice

of falling into abstractions—abstract images,

he calls them—as a way to escape his own

severe anxieties and circumstances (letters, 21 Sept). He still has thoughts about

poetic fame

trailing from his Huntian days, but it is no longer a clamoring, restrictive, and

even

embarrassing topic, as it is in his early poetry, where laurels seem to be easily

earned and

exchanged.

Keats now requires of himself a larger, selfless scale in his poetry-to-come, as well as an elevated but controlled idiom. With Shakespeare at his back and Milton in his mind, he attempts to write a poem that will, he hopes, embody his new, more mature seriousness: Hyperion. In a way, Hyperion is King Lear-meets-Paradise Lost. This combination is complex and daunting, yet stretches in Hyperion to display a level of performance to match those great precursor texts. Keats’s rising accomplishment is, mainly, to balance intensity and disinterestedness, and to muster a tone much less overtly poeticized. Unfortunately, most of his momentum for the poem’s completion is lost by December, the month Tom passes away. He will have to wait a few fallow months to continue his progress in new and mainly lyrical forms. His serious and deliberate study of poetry—of Shakespeare, Milton, and Wordsworth in particular, as well as of poetic form, combined with recent weighty personal experience and close contact with friends who seriously and critically think about art and literature—help to swell Keats’s poetic progress into his final year of writing, 1819.

And are Keats’s ideas in his 27 October letter to Woodhouse striking? To us, of course, they are. But they are distinctive enough to

Woodhouse that he immediately (and with some gusto) re-articulates them to John Taylor, Keats’s publisher. Woodhouse believes that their

young, developing poet is fully correct in his ideas and poetic distinctions. Remarkably,

Woodhouse suggests that Shakespeare is the only poet besides Keats who possessed this

[poetical] power.

And Woodhouse writes this without Keats having yet written nearly his

best poetry! But within a few months this poetry will show up—and Woodhouse, always

a close

reader of Keats, clearly sees it coming.