12 August 1820: Keats: Excessively Nervous

& Cheating the Consumption

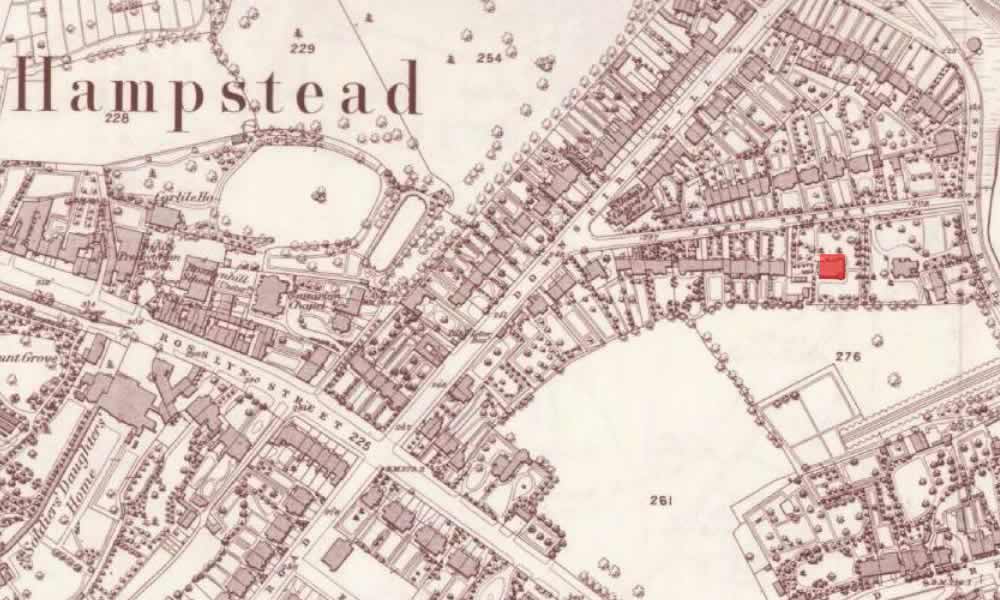

Wentworth Place, Hampstead

Wentworth Place, Hampstead: After about seven weeks staying with his friend and one-time mentor Leigh Hunt and Hunt’s somewhat hectic family (with five children running around) at Mortimer Terrace in Kentish Town, Keats on 12 August returns to Wentworth Place in Hampstead to stay with the Brawne family: a widowed mother and her three children, one to whom Keats is betrothed. Her name is Fanny, and Keats wears her ring. Keats had formerly stayed in the other half of Wentworth Place (a detached double-house, which, in English terms, can be called a villa). It has been a wet summer, and poor Keats is not in very good shape, and the sympathies and care of Mrs. Brawne are considerable.

Beginning early May, Keats has been living at 2 Wesleyan Place, Kentish Town, around

the

corner from Hunt. After a bout of blood-spitting

(technically, hemoptysis) on 22 June, the next day by invitation Keats moves in with

the Hunts

at 13 Mortimer Terrace so that his condition can monitored. While at the Hunt residence,

Keats

becomes very upset when he discovers that a letter to him from Fanny is opened (unintentionally, it seems) by someone in the Hunt

household, and so he leaves in a distraught state. Not long after, Keats apologizes

for his

exaggerated response; he lets Hunt know as much, and that he feels genuinely touched

by Hunt’s

patience and many sympathies

(letters, 13 Aug).

With medical advice and the support of others who are very worried about him, Keats

since

early July seriously considers a move to Italy in an attempt to restore his sinking

health.

Those close to him note his extremely poor and increasingly emaciated state. By mid-August,

it

is determined that he will go to Italy. Keats writes, another winter in England would, I

have not a doubt, kill me

(letters, 14 Aug). But beyond this vague hope, Keats almost

certainly knows enough that his days are numbered; as mentioned below, his knowledge

of the

illness—consumption—is considerable, given both his family history and medical training.

[For

much more on Keats and consumption, see 3 February 1820.]

Keats will somehow need to raise the money as well as find someone to accompany him. He hopes to go with his very good friend Charles Brown, with whom he has previously lived and travelled. By the end of the month, Keats asks for money from the often inflexible trustee of the family money, Richard Abbey; Abbey refuses to give him anything, claiming his own financial shortcomings (letters, 23 Aug). Keats barely manages to get by with loans from generous friends like John Taylor and Brown. Keats seems to have spent up the capital he was aware of, having lived for a couple of years based on credit from that capital, inherited from his maternal grandmother. He is unaware that a significant sum (perhaps about 800 pounds) is actually available to him via the courts (Chancery), left to him by his maternal grandfather (in today’s terms, perhaps approaching 80,000 pounds). It appears Abbey is also unaware of this money, which has been building with interest.

Keats understandably displays and expresses anxieties: witnessing his own mother and younger brother, Tom, die from consumption no doubt burdens him. Yet, on 13

August, Keats says that he half believes his illness is not yet Consumption,

and ten

days later he expresses some hopes of cheating the Consumption.

This, though, goes

against the direction of his symptoms, and especially the hemoptysis and what appears

to be

increasing physical incapacity. Hope can be delusive. The so-called wasting

disease

—pulmonary tuberculosis—seldom lets go, and the decline of its victims can often

take more than a year to resolve itself in a horrible end. In short, Keats has grave

doubts

about his immediate future: mid-August he composes a short will that stipulates that

Brown and John

Taylor be first paid

from his estate, and that his books be divided among

my friends.

At age twenty-four, you don’t make a will unless you believe there are

problems.

Keats’s situation and pronounced nervous state both magnify and twist his regard for

Fanny Brawne. Over July and into August, Keats in

fatalistic terms tells her that he cannot live without her. He is possessive and jealous

in

the extreme, and, by throwing out frantic ultimatums, he emotionally manipulates her

by

attempting to control her behavior and feelings. I am sickened at the brute world which you

are smiling with,

he writes to her. I hate men and women more.

The world, he

says, is too brutal,

and he says that only in the grave might he have some rest.

Keats’s feelings for Fanny have fallen into and merged with other parts of his distressed

state and situation, so much so that at moments despondency and anger take command

over his

emotional life.

At the end of August, Keats hemorrhages again, and his prospects and strength decline

further. He reports a couple of times that his chest is tight and agitated. Everything,

it

seems, taxes and tires him. These are, of course, symptoms of his illness and corresponding

state of mind. To his sister (from whom he often

shelters his more dire thoughts) he writes, I am excessively nervous

(13 Aug). One of

Keats’s friends, the young painter Joseph Severn

(who will eventually accompany Keats to Italy), reports that in July Keats’s appearance is

shocking,

and that it reminds him of how Keats’s younger brother, Tom, looked before he died of consumption in December 1818.

Poor Tom becomes poor Keats.

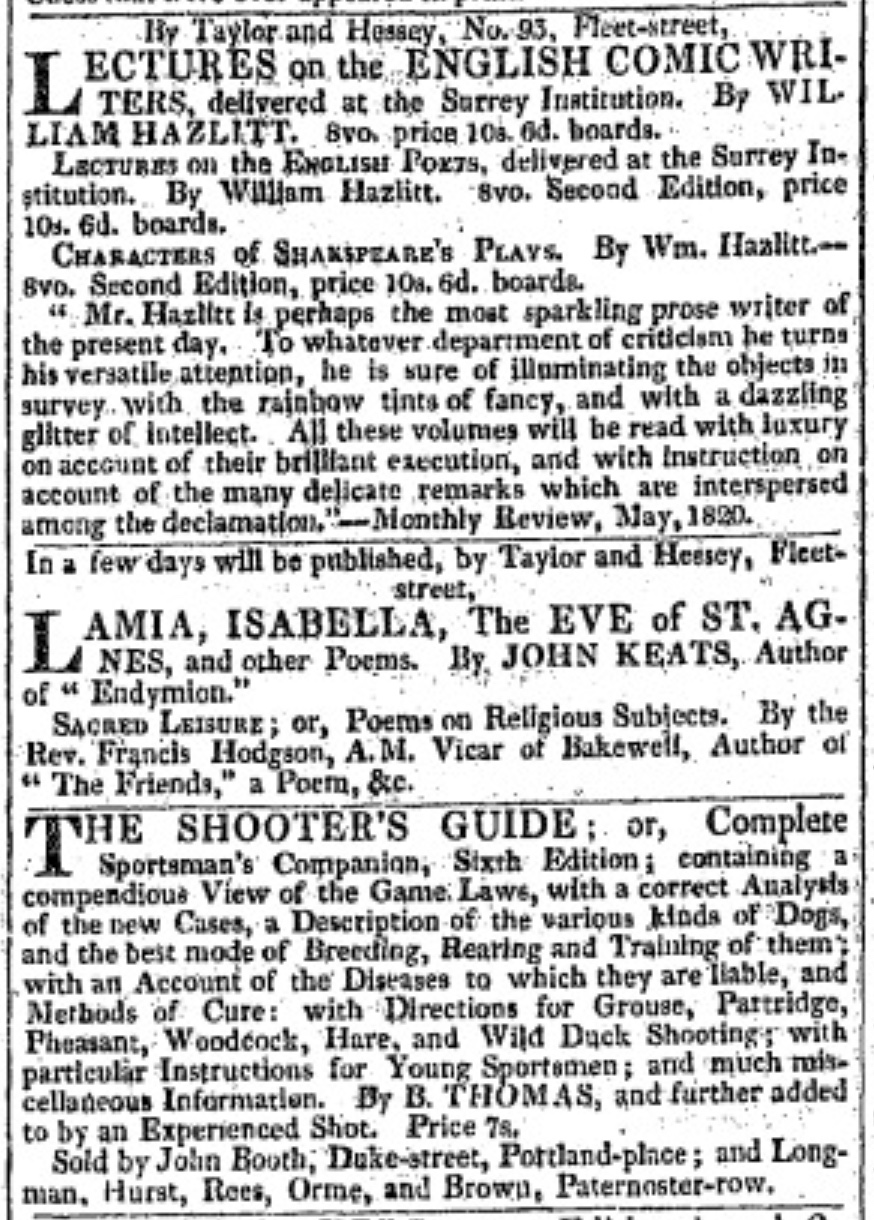

Perhaps Keats’s greatest (or only) relief about this time is that his 1820 volume

Lamia, Isabella, The Eve of St. Agnes, and Other Poems (1820) is

published between 26 June and 3 July. It receives decent reviews with what Keats calls

the

literary people

(letters, 14 Aug); sales, he believes, are moderate

(letters,

14 Aug, to Brown). A few of Keats’s friends believe the volume displays vast power

and genius,

and more favorable reviews begin to appear. Those who study and recognize his gifts

and

originality are right, and the collection will become one of the strongest in the

English

canon, capping Keats’s halted progress. Most of the thirteen poems in the volume possess

a

style, voice, and thematics that can profitably be called Keatsian. His voice of independence

and remarkable originality—sensual intelligence? intelligent sensuality? restrained

intensity?

intense restraint?—is, in many of the poems, expressed in clear, uncluttered, dramatic,

and

enduring ways.