24 October 1818: Romantic Encounters, Sublime Solitude, & Passion for the Beautiful; Keats’s Predicted Greatness

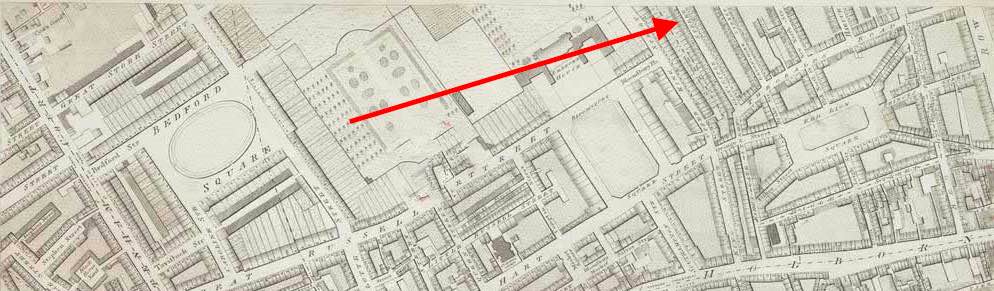

34 Gloucester Street, London

The home of the enigmatic (at least for Keats) Mrs. Isabella Jones, with whom Keats has had an earlier romantic encounter near Hastings (in an adjacent village with the delightful name of Bo-Peep), May 1817.

On this day, a week before his twenty-third birthday, Keats has passed Isabella on the street. He turns back to greet the stylish and

attractive woman, and, probably after some niceties and a short detour to see one

of her

friends who managed a boarding school, he presses a little so that he can walk her

home, to 34

Gloucester Street, off Queen Square, wondering all the while what it might lead to.

As he will

write in a letter to his brother and sister-in-law in America (George and Georgiana)

that describes the encounter, She has always been an enigma to me

(24 Oct 1818). They

spend some time in, he notes, her very sitting room, with all its books, pictures,

statues,

aeolian harp, music, and liquor—not to mention a couple of birds as well as a bronze

statue of

Napoleon, which might suggests something about her free-thinking yet genteel manner.

In a

typical Keatsian fashion, he uses a sensuous metaphor to describe the room: its tasty,

he writes. But nothing romantic happens. Keats, however, seems to have thought a little

kiss

might not be a bad way to part. Isabella, without any prudishness or offence, thinks

otherwise. It seems a nice hand-pressing will have to do. Keats recalls that in his

earlier

encounter he had warmed with her before and kissed her,

though what exactly this means

is unclear—he differentiates warmed

from kissed,

so it could be something more

or something less than kissing. At this point, he concludes I have no libidinous thought

about her

(14-31 Oct 1818), though it seems otherwise. Keats then later notes he

receives much game—including pheasant—from Mrs. Jones, which he re-gifts. (This, of

course,

tempts a witty comment about what exactly, in this particular case, the bird-in-the-hand

proverb might suggest.) Keats also expresses that he would at some point like to develop

his

friendship with her—for, as he writes, her mind.

Though this clearly suggests some

desire on the part of Keats to develop their friendship, Keats and Isabella agree

to keep

their common acquaintances

from knowing the exact history of their relationship; but

everything tells us she has significant artistic and cultural sensibilities, and that

Isabella

is fairly well acquainted with others in Keats’s circle.

[For more about her and Keats’s first meeting with Isabella Jones, see May 1817.]

Mrs. Jones may be responsible for suggesting the Eve of St. Agnes as a poetic topic to Keats, which, in the first few months of 1819, he takes up (remarkably so!) in an engaging and remarkably atmospheric narrative poem. The poem contains a sexual encounter that, controversially, exists somewhere between an allegory of the sensual imagination and flesh-and-blood rape, coloured by deception.

Keats this month also expresses some barely closeted feelings about a certain Jane Cox, whom he meets via the Reynolds sisters. Within

a longer journal letter to his brother and sister-in-law in America, Keats on 14 October

bothers to describe her; she has, in fact, made Keats a little hot and bothered: Miss

Cox, he

writes, has fine eyes and fine manners,

and When she comes into a room she makes the

impression the same as the beauty of a leopardess [. . .] a man is drawn toward her

with a

magnetic power.

She intrigues him, and he confesses to losing some sleep thinking about

her.

In this journal letter (14-31 Oct) in which he writes about his personal circumstances,

Keats

also communicates, I hope I shall never marry.

He says, Solitude is sublime,

that there is Pleasure in Solitude,

and that he has a barrier against Matrimony

which I rejoice in.

The comments really point to Keats’s desire to find, as it were,

space to study, think about, and compose poetry.

The interesting feature about the ideas he develops this October is how he plays off

the

mighty abstract Idea of Beauty,

his strengthening imagination, and concerns about his

powers for poetry

against domestic happiness.

As mentioned, his desire for and

love of poetical solitude greatly outweigh any other personal circumstance. Keats’s

commitment

to poetry is clear and his path extraordinarily confident: I think I shall be among the

English Poets after my death,

he writes 14 October to George Keats. Ten days later, he sets out his determination and

direction: The only thing that can ever affect me personally for more than one short

passing day, is any doubt about my powers for poetry—I seldom have any.

And then a few

days later, in writing to Richard Woodhouse

and attempting to muster some resolve—and after articulating his own poetical character

as

the camelion Poet

—he writes, I will assay to reach to as high a summit on Poetry

as the nerve bestowed upon me will suffer

(letter, 27 Oct). As he assesses his own

happiness in light of solitude, he confesses the yearning Passion I have for the beautiful,

connected and made one with the ambition of the intellect.

This appears to be a passing

train of thought—Enough of this,

he adds—but the idea is clearly definitive in terms of

his progress: to embrace the truthfulness of beauty in a measured, controlled manner,

and to

attempt to carefully measure his own desire and abilities; these set the way for the

qualitative leap poetry takes into 1819.

Keats’s accumulating comments about poetic directions and conditions, as well as his confidence in his poetic powers, thus point to lurking, immanent achievement. He is reaching toward, and ready for, the power of poetry. For us, though, with the hindsight of knowing his actual achievement in 1819, this is an easy prediction.

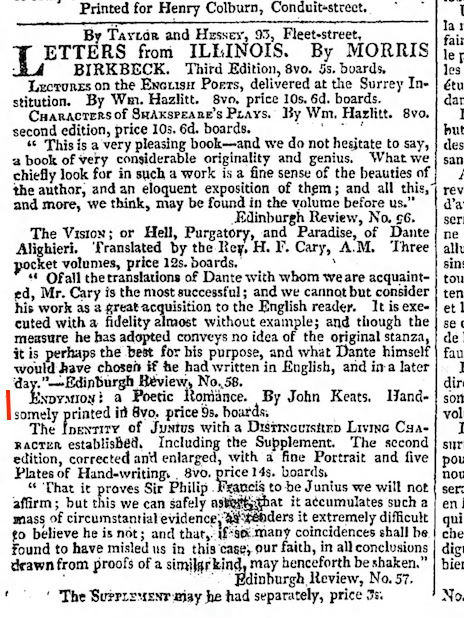

But this prediction of greatness is not just Keats’s. Woodhouse, who is realistic

and

tough-minded in his ideas about poetry and poetic greatness, this month writes to

a third

party at length about Keats’s poetic merits.

To Mary Frogley on 23 October, he

resolutely expresses his belief in Keats’s greater gifts: such original genius, I verily

believe, has not appeared since Shakespeare & Milton.

He knows Endymion displays the faults of early work, but Reynolds puts

himself out on a limb by prophesying now, while Keats is unknown unheeded, despised [and .

. .] neglected],

and if Keats lives to a usual age, and critics do not drive him from

the free air of the poetic heaven before his Wings are fullfledged,

that he will rank

on a level with the best of the past or of the present generation; and after his death

will

take his place at their head.

This is indeed a fully-felt conviction, but Woodhouse

claims he makes it in the spirit of true criticism.

Well, it turns out Woodhouse was

correct, except inasmuch as Keats’s wings will appear within months, not years. Winter

is

coming, with Spring not far behind.