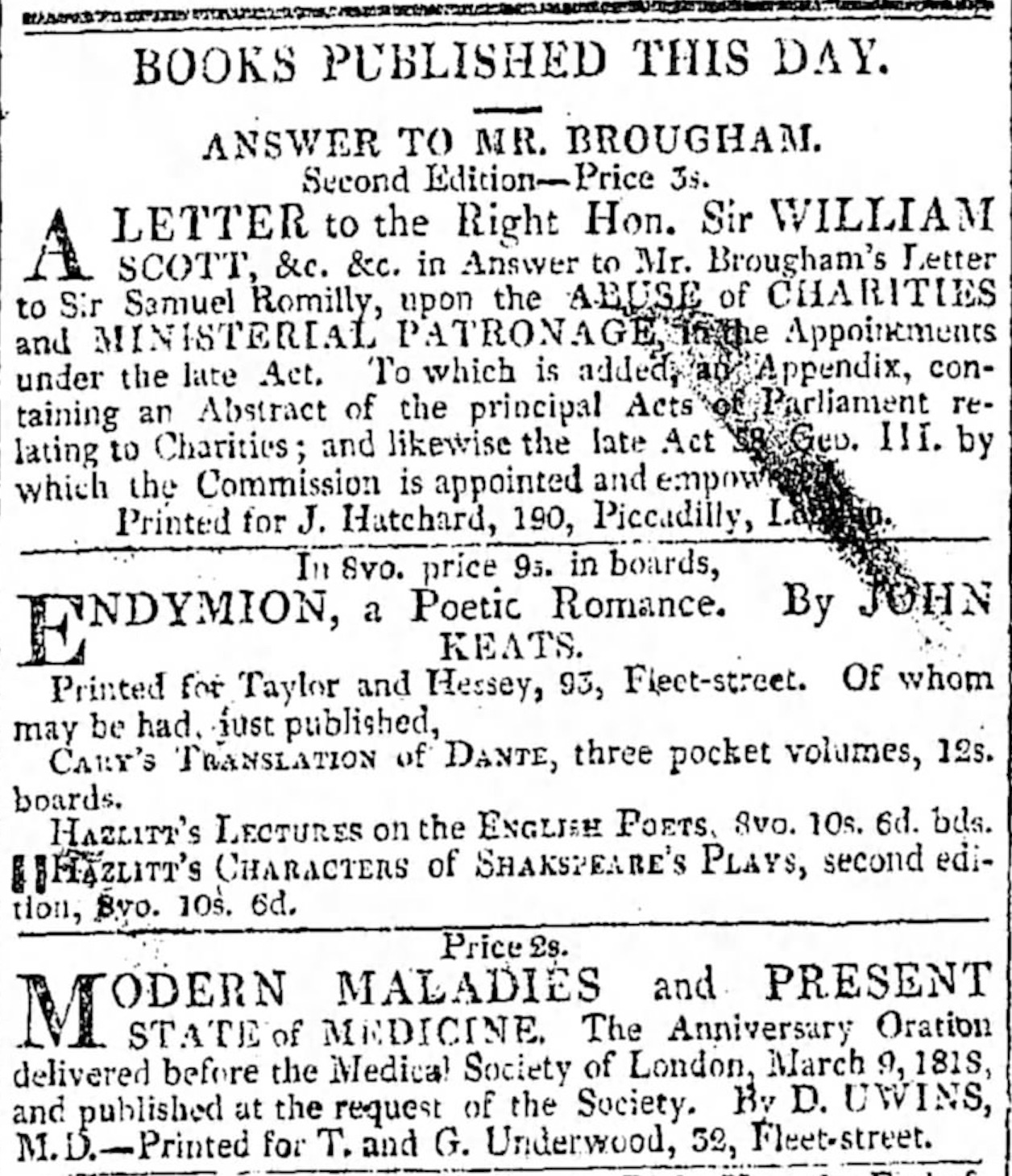

22 October 1818: Walking With Hazlitt, Thinking Like Hazlitt, Not Playing Rackets Like Hazlitt

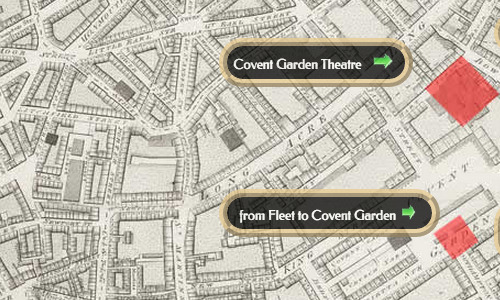

From Fleet Street to Covent Garden, London

From Fleet Street to Covent Garden: Keats walks with William Hazlitt, the literary critic, journalist, essayist, and lecturer. Hazlitt becomes an important, perhaps crucial, influence on Keats.

Keats finds Hazlitt’s depth of Taste

one of few things to rejoice at in the Age

(letters, 10 Jan 1818). Importantly, Hazlitt’s ideas propel Keats to think in terms

of

evaluative criticism—what’s good, what’s bad, and why; and Hazlitt’s approach (and

critical

vocabulary) pushes Keats toward understanding, valuing, and articulating the qualities

of

artistic genius and genuine feeling. This fully corresponds with Keats’s critical

and creative

inclinations—that is, to his developing poetics and poetry.

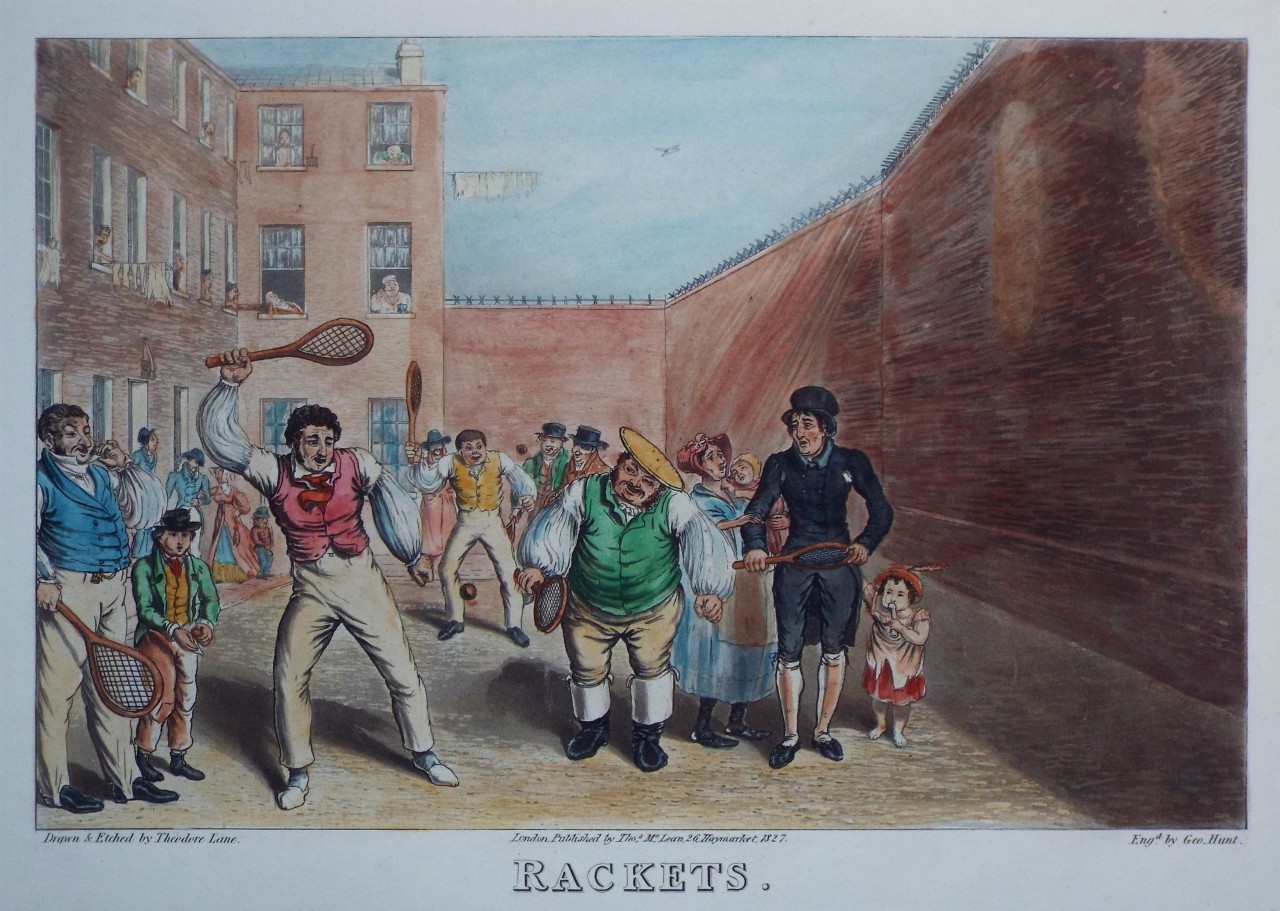

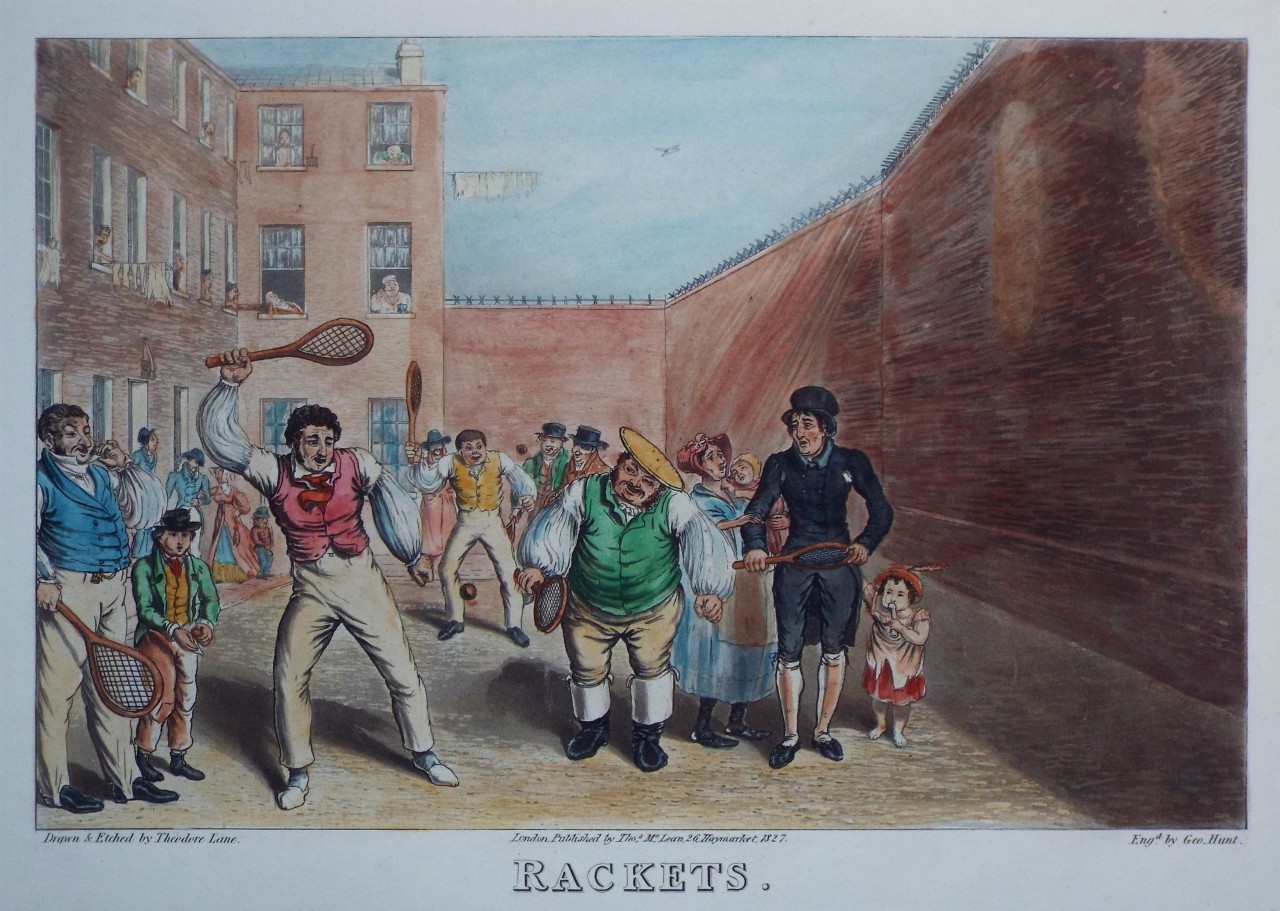

When Keats runs into Hazlitt in the middle of London, he discovers that Hazlitt is on his way to play Rackets

(letters, 24 Oct)—a

game that develops from hand-fives, with venues that use the back walls of taverns

and in

debtor’s jail, where, of course, there are plenty of walls (the addition of racquets

speeds up

the game, and eventually evolves into squash). Hazlitt is apparently pretty good and

relishes

taking on all comers. He loves the game, and he almost worships the prowess of the

best fives

player of the era, John Cavanagh (d.1819). Hazlitt, in fact, will write a famous obituary

about the peerless Cavanagh (an Irish house-painter), in which he is almost as interested

in

taking a few jabs at some in the contemporary literary scene (published in The Examiner 7 February 1919, pp.94-95). What Hazlitt admires so

much is Cavanagh’s skill, his precision, his easeful power, and his ability to read

the

weaknesses of his adversaries—in short, the tack Hazlitt often takes in his own critical

work.

Those who watch Hazlitt play witness an intense, hyper-competitive player, capable

of

screaming, swearing, stomping, groaning, and throwing his racquet in frustration;

it seems he

does not like to lose or make mistakes. One is tempted to say his on-court performance

is

simply an outlet for his more cerebral work; but, perhaps closer to the truth, his

on-court

behavior might be seen as an extension of his life of the mind. That is, as a writer,

Hazlitt

often exhibits an equally competitive side: he does not take prisoners, he never likes

to lose

an argument, and he is not shy about displaying his emotional side. He needs to have

the final

word—that is, make the winning or parting shot. Some of this does not quite sync with

what

Hazlitt says about the game, when he also notes that playing it is a good way to relax

the

mind. Perhaps, in his case, divert

the mind might be better description, given the

pressures of Hazlitt’s cultural battles.

Although Keats and Hazlitt first meet in late 1816, Hazlitt’s influence on Keats grows strongly from at least as early as September 1817 (Keats reads some of the Round Table essays) and into early 1818, when Keats attends some of Hazlitt’s famous lectures on poetry.

Besides pointing Keats toward his considered views on key writers, Hazlitt’s theories of imaginative identification—that the imagination is primarily sympathetic—are taken up and applied by Keats in his exceptionally acute ideas about poetic character (see below). In turn, these ideas soon work themselves into Keats’s best poetry.

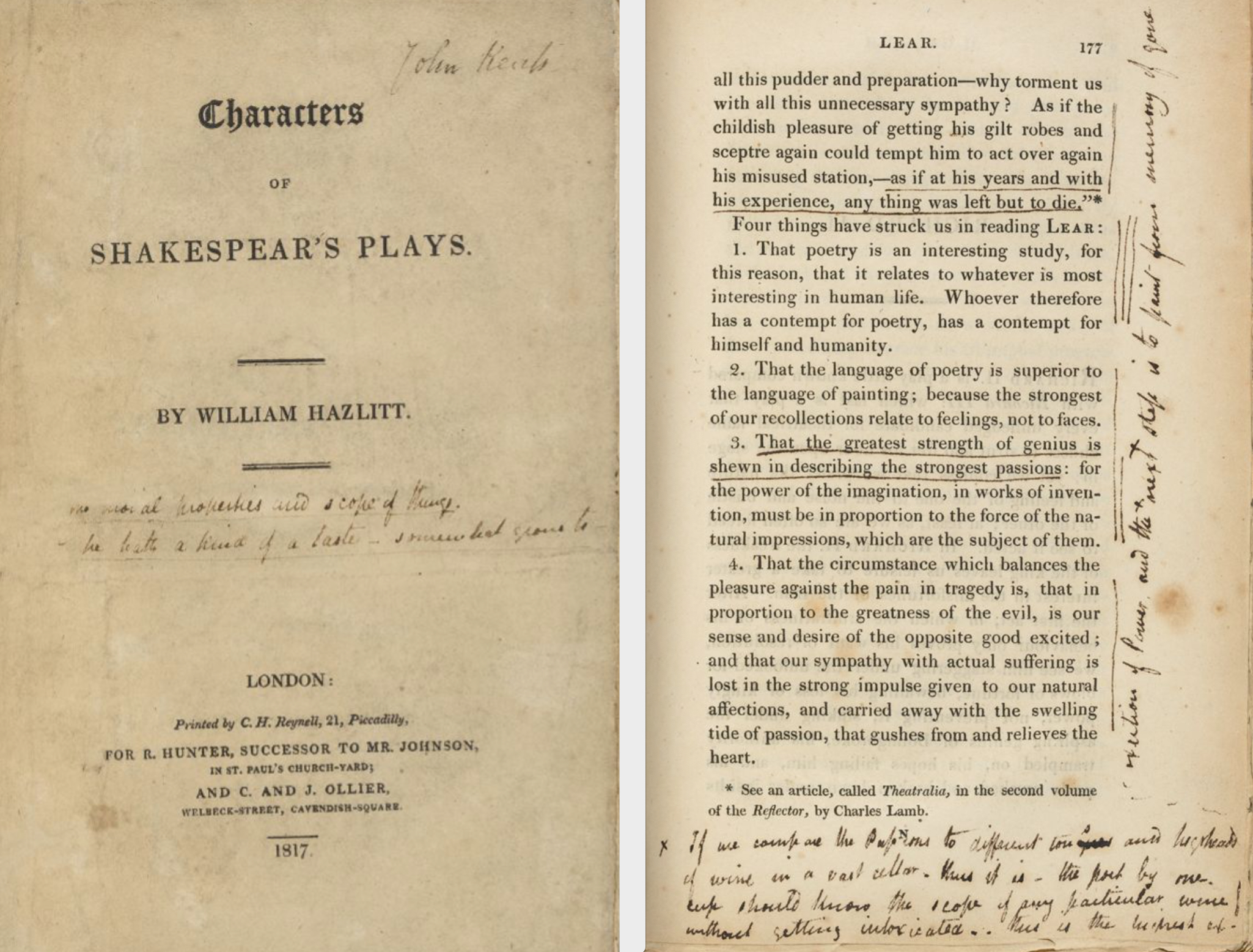

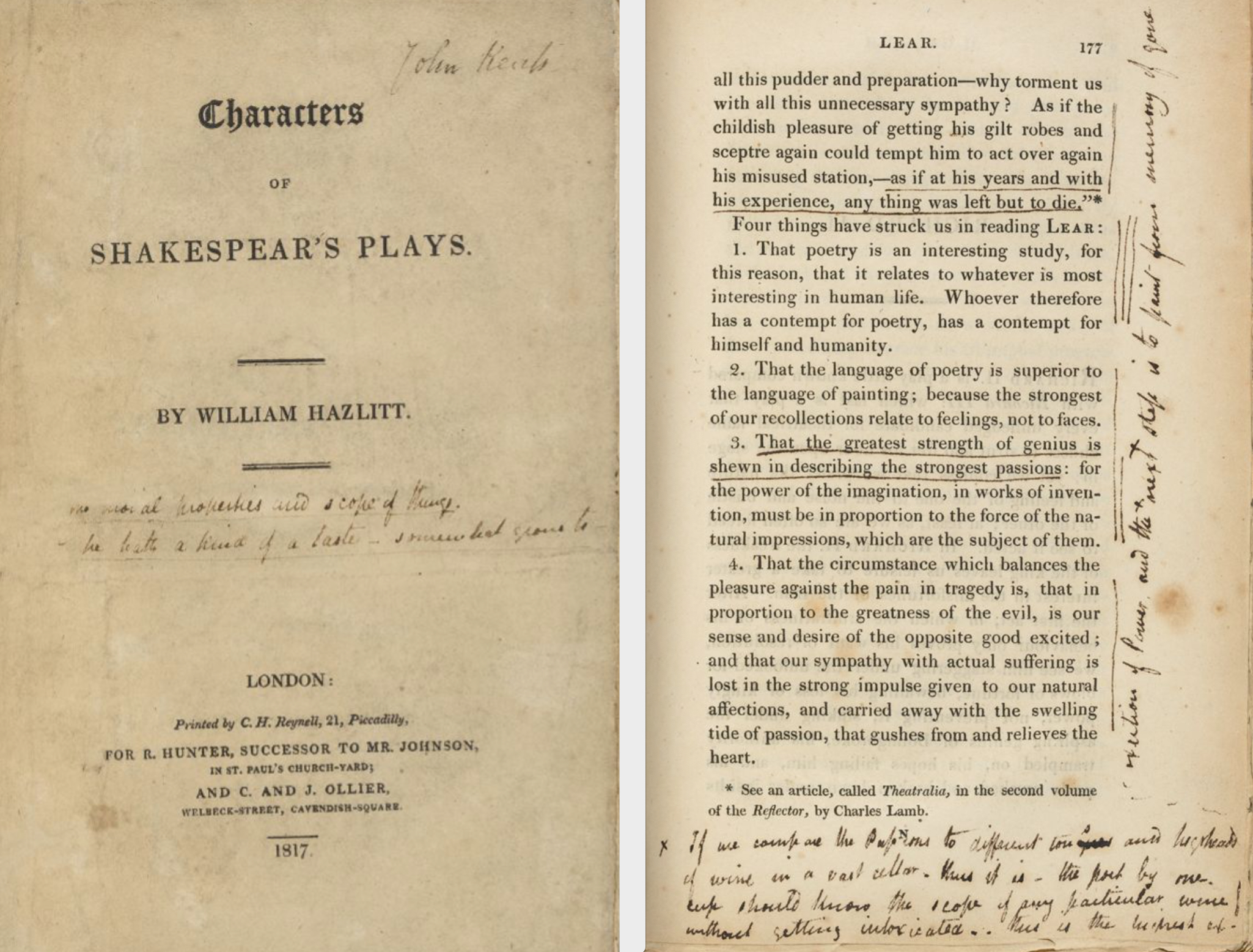

Keats also reads Hazlitt’s 1817 Characters of Shakespear’s Plays. In particular, we see Keats critically parse Hazlitt’s chapter on Shakespeare’s King Lear, a play that Keats has been reading for some time (a reference to Lear appears in what may be Keats’s earliest surviving poem, the 1814 Imitation of Spenser).

For Hazlitt, King Lear is Shakespeare’s best play, and almost beyond commentary and

comparison. Keats’s marking and marginalia in Hazlitt’s chapter* show how intensely

engaged he

is with what Hazlitt writes about the powerful uncertainty—the ebb and flow

(p.157)—of

natural feelings and passions expressed through acts of Shakespearean imagination,

those that,

in Hazlitt’s words, lay open the deepest movements of the heart

(p.177). It is the

play, Hazlitt writes, that strikes deepest into the human heart

(p.153). This, Hazlitt

concludes, is what constitutes true poetic genius—and what Keats will strive for in

his own

work. In fact, this is the exact trope Keats’s uses in assessing true poetic depth,

and, in

particular, in assessing the nature of William Wordsworth’s superlative powers: it

is because,

as Keats puts it, Wordsworth thinks into the human heart

(letters, 3 May 1818).

And in early 1818, just when Keats may be reading Hazlitt’s chapter on King Lear, he

writes a sonnet about preparing to read the play. In the poem—On Sitting Down to Read King Lear Again—he points to the impassioned

Shakespearean dispute

that exits between the contraries of damnation and creation,

between death and life, and he points to the bitter sweet

that comes when reading a

play so dark, so true, and yet so beautiful; in the end, through the play’s inspiration,

he

hopes to have his poetic aspirations reborn: Give me new phoenix wings to fly at my

desire.

This, in a way, points to a new beginning for Keats in his poetic progress.

For Keats, that progress comes first in the form of poetic theory: Keats might not

have

developed his notion of Negative Capability

(27 Dec 1817) without Hazlitt’s

fueling ideas; and his new poetics articulated at the end of October 1818—how, as

the

camelion Poet,

he wants to be distinguished from the wordsworthian or egotistical

sublime

—almost certainly derive from his accumulative reading of and contact with

Hazlitt. Specifically, Keats adopts some of his terminology from Hazlitt, and in particular,

disinterestedness,

which Hazlitt first describes in his 1805 Essay on the Principles of Human Action: An Argument in Defence of the Natural

Disinterestedness of the Human Mind. Here, Hazlitt argues that entering the identity

or perspective of another is in fact natural and not a form of egotism, and from this

it is

only a sideways step to how Keats merges this into his own idea of how the poet can

assume the

qualities and character of his subject, thus leaving the ego behind—the camelion poet

has,

according to Keats, no self.

This is a decisive step forward in Keats’s thinking: he

considers disinterestedness a supreme human quality, while also drawing upon Hazlitt’s

terminology of artistic power, passion, and vitality—gusto

(letters 13 Jan 1818, 19

March 1819). If there is a difference between Hazlitt’s and Keats’s creative and critical

theories, it is that Hazlitt moves toward the idea that the artist creates or illuminates

the

subject, while, for Keats, the artist becomes (or is consumed by) the subject.

Keats’s ideas about his own Poetic Character

and that a poet has no identity

are arousing enough that, at length, the ever-encouraging Richard Woodhouse reports and quotes them to others to support

his belief in Keats’s genius. Even at this point, Woodhouse is convinced that Keats

will

eventually stand as a literary great.

In short, Keats is now able to articulate the point that superior, enduring art—and poetry—does much more than simply represent. It reaches out, it pulls in, it complicates, and it transforms. This, in Keats’s term, is intensity. And this is what Keats now aims toward.

October may mark this leap in Keats’s thinking, but the month is also taken with attending

to

his younger brother’s—Tom’s—quickly slipping

health; he will pass away within weeks. Keats nevertheless manages to have contact

with at

least a dozen of his friends during the month. He writes, I have too many interruptions to

a train of feeling to be able to write poetry

(21 Oct). But, again, at least he can

think about it, and Tom’s death no doubt presses ideas of purpose and meaning upon

Keats.

[For more on Hazlitt’s influence on Negative Capability, and where gusto

is mentioned,

see 27 December 1817.]