16 February 1821: Another Death Brewing: The Scott-Christie Duel & Keats’s Greatness

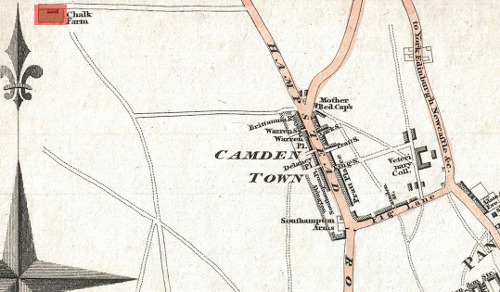

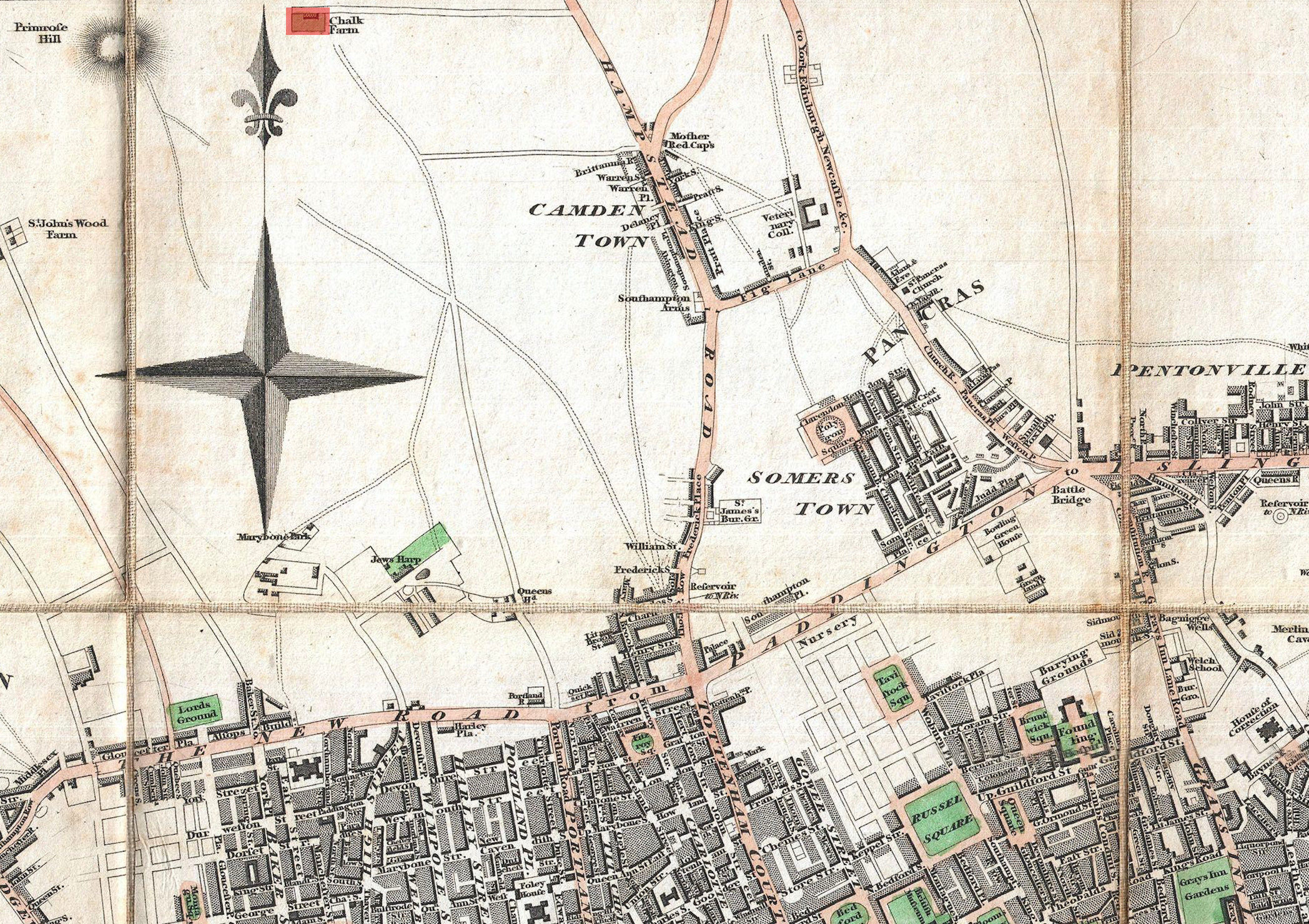

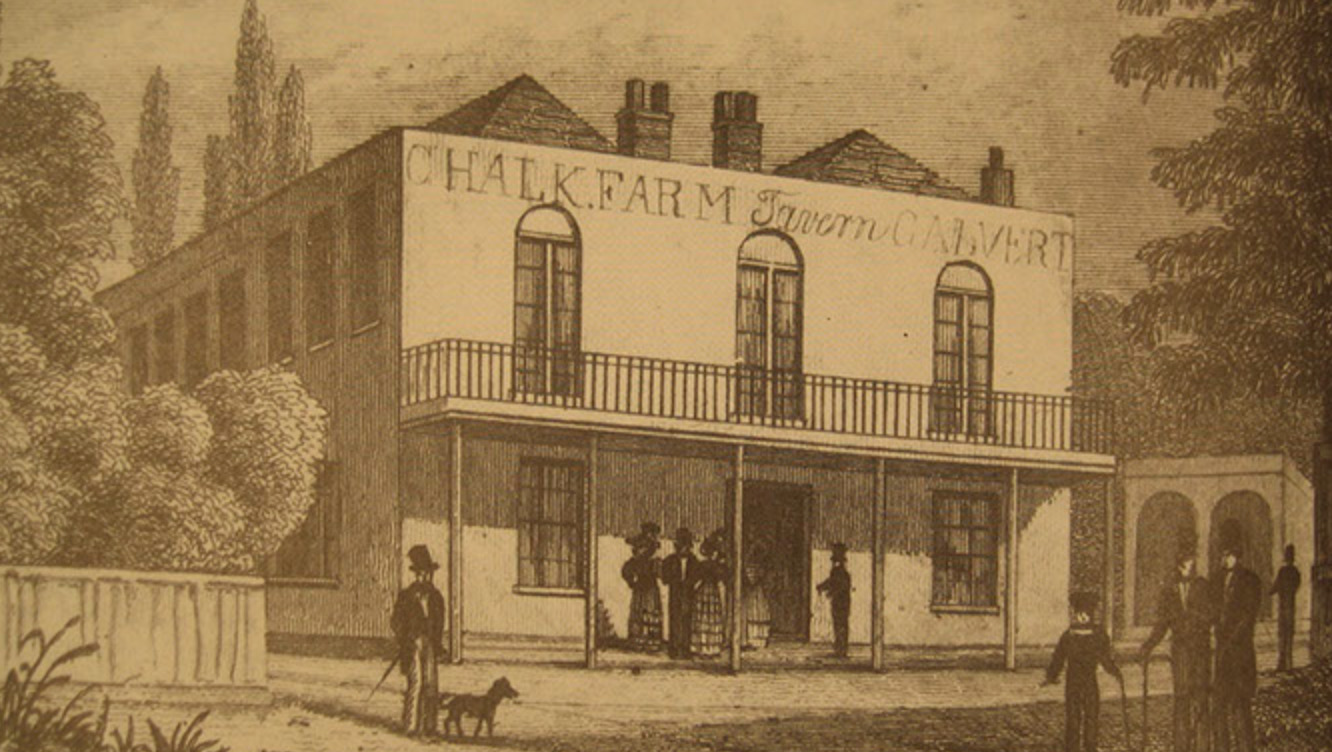

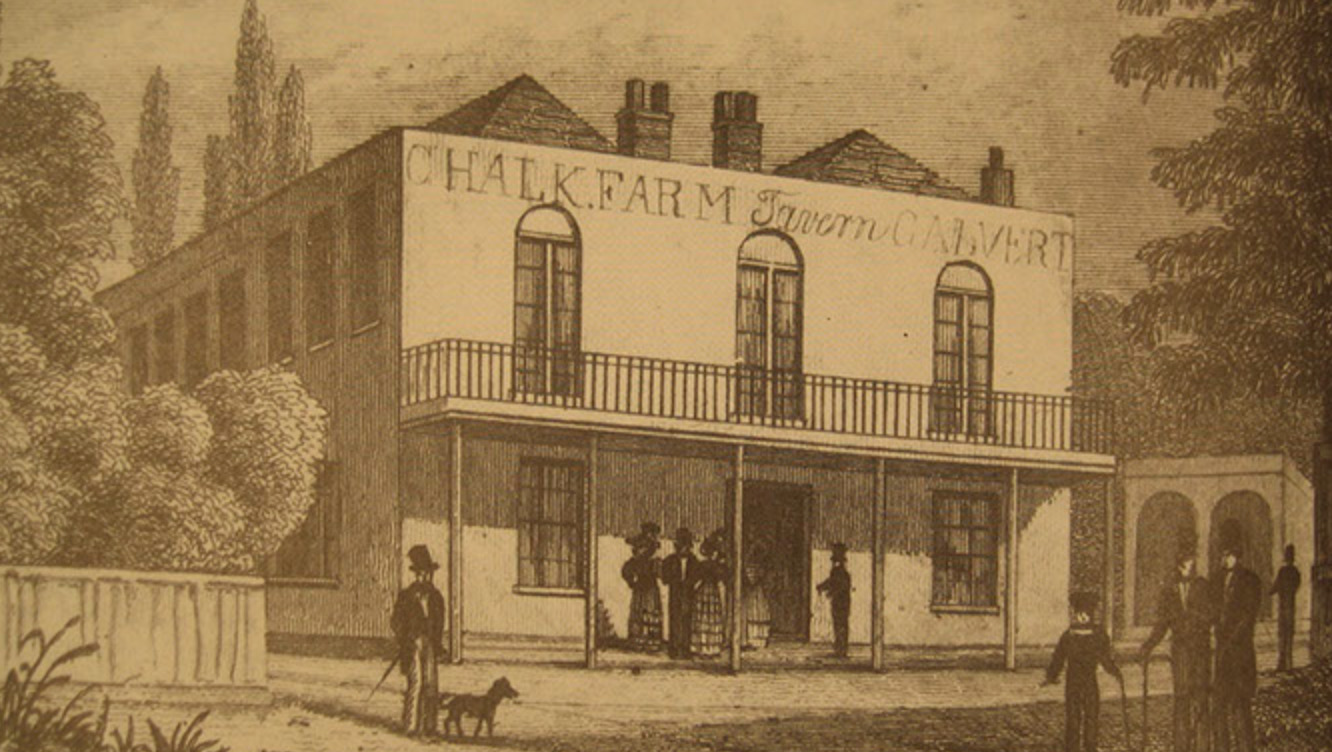

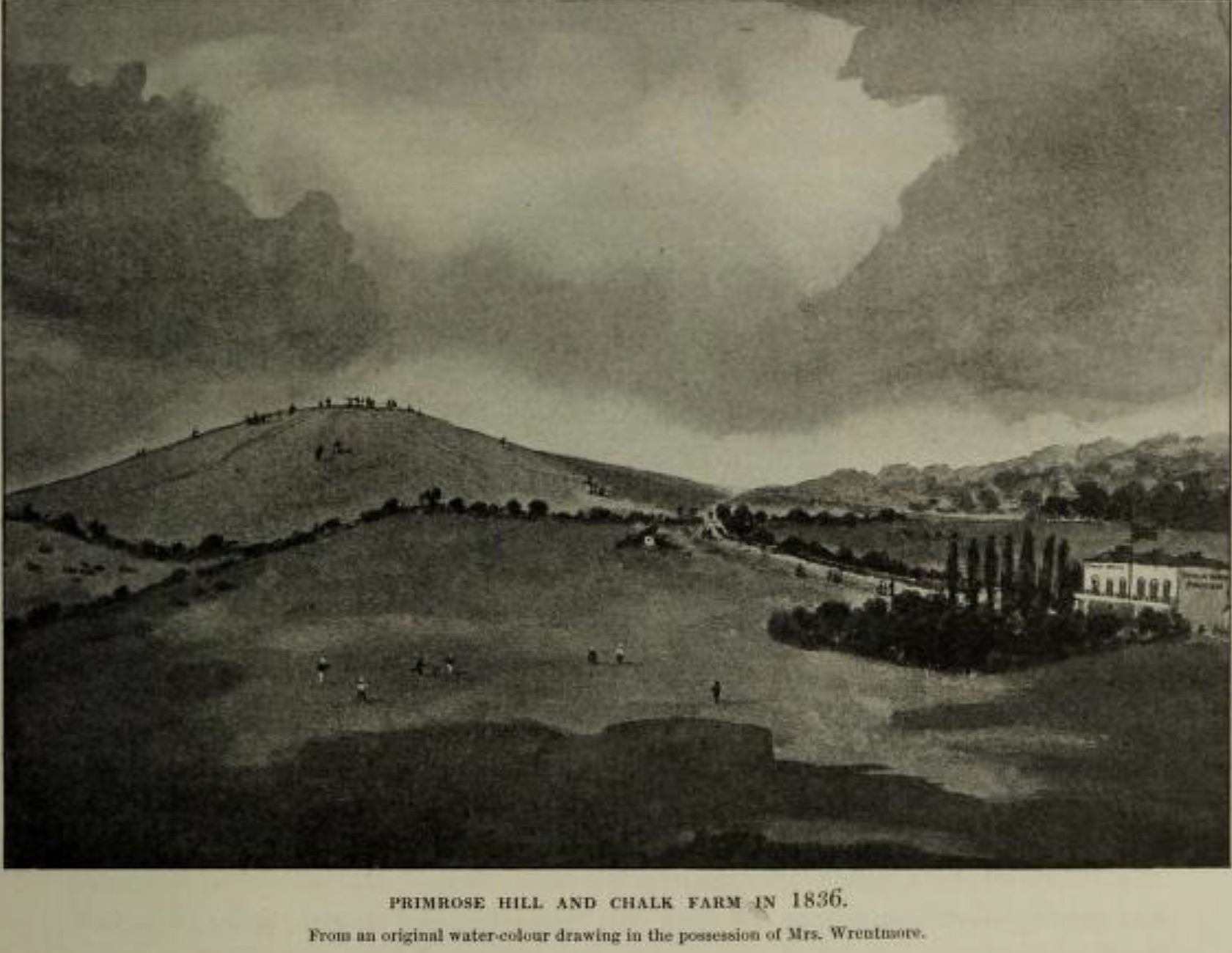

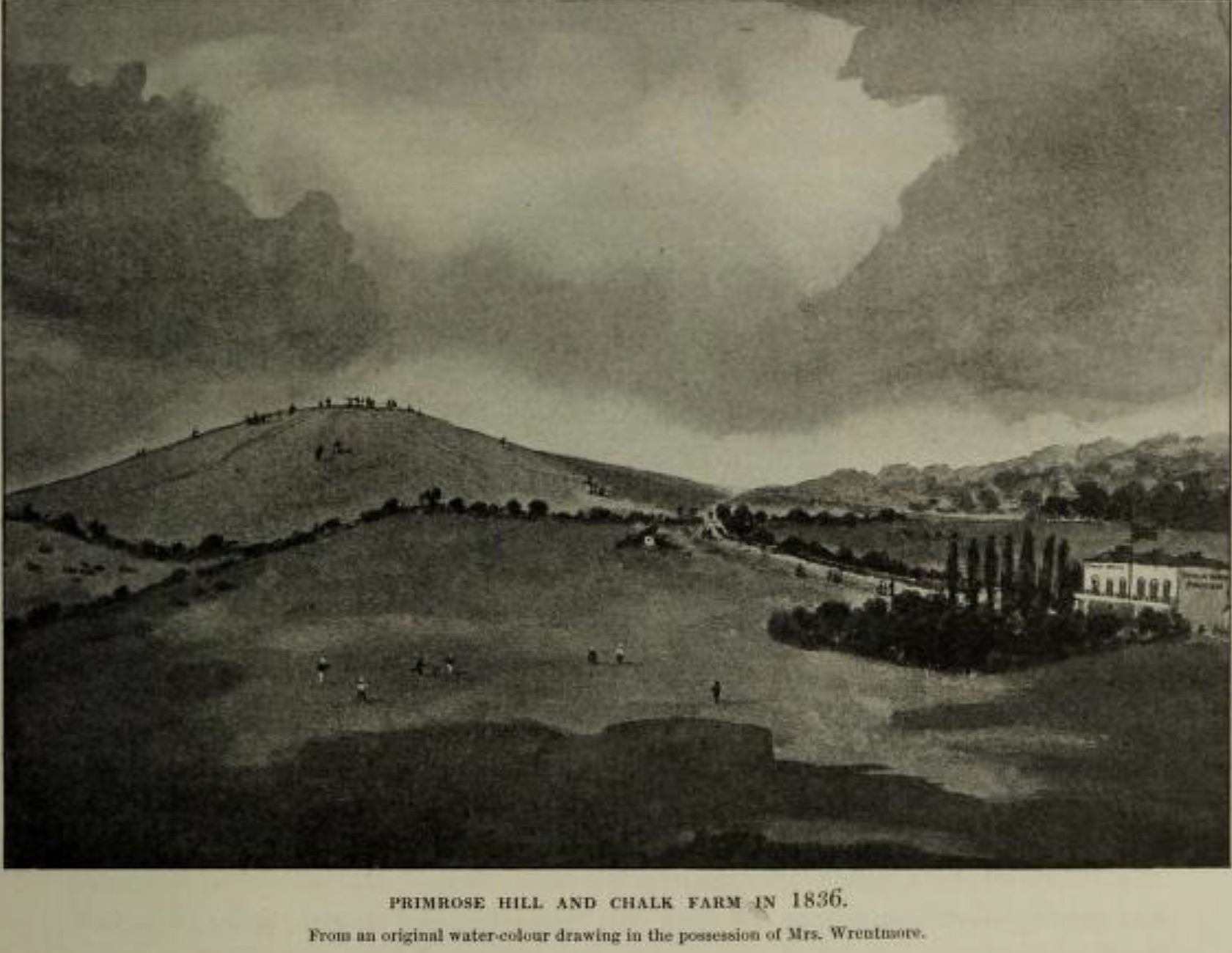

Chalk Farm, Northwest of London

At this very moment, while Keats slides hopelessly toward his imminent death in Italy, another death brews, one with ties to Keats’s poetry and poetic reputation, and involving people Keats knows. This death, though, is hardly an unstoppable illness; rather, for the last few months and up until this moment, it has been gaining its own tragic and confused momentum. Besides the flaws of personality and cultural practice, it reflects on the entrenched complexity the culture wars within Regency Britain: the old order was under increasing pressure from progressive, protesting forces; Keats’s circle was, for the most part, firmly on the side of the latter.

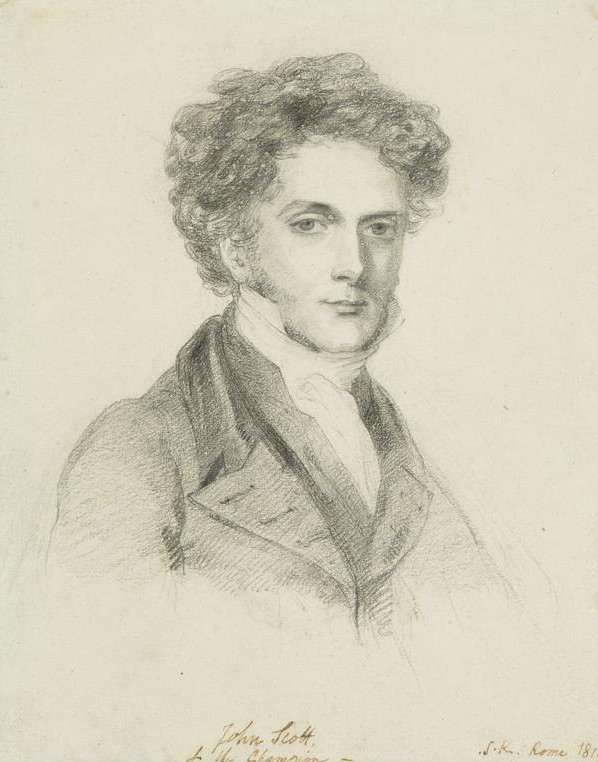

It involves John Scott, arch-liberal and former

editor of The Champion and now of The London Magazine. In intersecting with Keats’s life, we remember Scott in a

number of ways: as meeting Keats’s younger brothers, Tom and George, in Paris, September

1817, at which time Scott could have acquired his copy-book of some of Keats’s early

poems,

made by Tom; as involved with publishing Keats in The

Champion; for publishing a positive two-part review of Keats’s Endymion in June 1818

in The Champion; later, in October 1818, in a newspaper

letter (in The Morning Chronicle), for publicly defending

Keats against an attack made in The Quarterly Review; for

being considered by Keats’s very close friend, Charles

Brown, as the publisher of Brown’s account of his northern tour with Keats; and

finally, for a long review of Keats’s final collection in the September 1820 London Magazine, that opens with unleashed disgust over how

Keats has been treated in both the ultra-Tory Blackwood’s Edinburgh

Magazine—by John Gibson Lockhart,

writing as Z

—and also in The Quarterly Review, by

John Wilson Croker. Scott writes,

Perhaps from the whole history of criticism, real and pretended, nothing more truly unprincipled than that abuse can be quoted; nothing more heartless, more vindictive,—more nefarious in design, more pitiful and paltry in spirit.

Scott, then, knew Keats’s work very well (and certainly did not find it without particular faults), but he feels driven to defend the integrity of professional, responsible criticism, and Keats along with it. Scott becomes increasingly enraged by how Lockhart can, under Blackwood’s banner, utterly condemn Hunt, not just as the overseer of the so-called Cockney School of poetry (to which Keats is affixed as Hunt’s boyish intern), but for nasty partisanship that colours literary criticism and poetic tastes with politics, class, and plain, sinister character assassination. (Oddly, because of an earlier disagreement over Lord Byron’s merits, Hunt for a while actually thinks Scott is “Z”!)

The affair between Scott and Lockhart/Blackwood’s eventually moves to a point where Scott, in The London Magazine over November and December 1820 and into January 1921, accuses Lockhart by name of being a liar. Scott, for his part, is counted by being called, among other things, a coward. Public attacks and counterattacks are flung back and forth. Entrenched in their positions and as a matter of honour, the matter is taken to the extreme—to a duel—unless retractions or explanations are immediately forthcoming from Lockhart. Scott does offer ways out of the conflict if Lockhart can put in writing that he did not profit from the articles he wrote for Blackwood’s.

Numerous mitigating attempts, hurried written exchanges, bad advice, and cloudy legalities come to nothing over matters as simple as a little wording, meaningless admissions, and uncertain disavowals. Jonathan Christie, Lockhart’s very close friend and staunch supporter, as well as London agent for Blackwood’s, acts for Lockhart in the duel, having now involved himself in slighting Scott’s character, and therefore Scott now challenges Christie. Another of Keats’s close friends, Benjamin Bailey, knew both Christie and Lockhart, and liked the former and disliked the latter.

And so, in the late, freezing evening of 16 February, a little outside of London at a site (known for dueling) just beyond Chalk Farm Tavern, Christie mortally wounds Scott on a second round of firing during the duel. Scott, aged thirty-six, father of two, dies of the stomach wound eleven days later, just a few days after Keats himself passes away.

The tragedy is compounded: the second round of the duel should never have taken place, since Christie, unknown to Scott, actually fires into the air on the first round, thus signaling an end to the duel. Thus honour can be saved without shame on either side (deloped is the technical term). However, miscommunication and incompetence (aided by the uncertainty of evening light) take the duel to that fatal second round.

Keats, of course, will know nothing of the event. But while it was building to that point, Brown writes to Keats 21 December 1820, when Keats’s own fate is sealed by consumption’s agonizing path: Brown is tickled to report that one of Blackwood’s gang is being publicly assailed by Scott, and he hopes Keats might be happy about the news.

On the night of the duel, we have to picture Keats, down in Italy on his deathbed, barely alive and living solely on milk. And Scott, there in England, on the cold, damp grass, days away from his own death, dying in defense of—well, what? Honor? Literary ethics? Poetry? Free thinking?

Small literary world that Regency London is, Keats, in November 1817, actually meets Christie, the man who kills Scott, under amiable circumstances via Keats’s close mutual friend, John Hamilton Reynolds. An irony: Keats did not apparently like Scott.

Personality and politics are an uneasy mix. And then we have Keats, who, in his poetry, purposefully attempts to rise above both. And that might be his point, and wherein his greatness lies.

For accounts of the duel and the legal proceedings, you can (below) read the original coverage in The Morning Chronicle for 14 April 1821 and in The Examiner for 4 March 1821, as well as transcriptions following. First, here is the original reporting in The Morning Chronicle:

[Transcription from The Morning Chronicle:] ACCIDENTS, OFFENCES, &c.

INQUEST ON MR. SCOTT.—On Thursday and Friday, an Inquest was held at Chalk Farm House on the body of John Scott, Esq. aged 40, who was mortally wounded in the late duel near that farm. The circumstances of this lamentable case are already before the public. The hostler belonging to Chalk Farm Tavern saw most of what took place. Two Gentlemen called at the Tavern on the night of the duel, a short time before it took place, and called for a bottle of wine and two glasses of negus, of which they drank and paid for, leaving the two last partly unfinished, observing that they would return in a few moments. Soon after he heard the reports of a pistol, and then another. Another Gentleman came for assistance, saying his friend had met with an accident. They took a shutter and found the deceased laying on his back, covered with a coat and a military cloak. The parties were 40 yards distant from him, conversing together. On arriving at the farm-house, Mr. Scott displayed symptoms of the most acute agony. The feelings of Mr. Christie were not less acutely painful; he repeatedly expressed a wish that he was in that situation instead of Mr. Scott.—Dr. G. Darling’s testimony was important. He attended the deceased frequently, and attributes his death to the wound which he received. Mr. Scott referring to his wound on Saturday morning between nine and ten o’clock, said, “This ought not to have taken place; I suspect some great mismanagement—there was no occasion for a second fire.” After a short pause, he proceeded—“All I required from Mr. Christie was, a declaration that he meant no reflection on my character. This he refused, and the meeting became inevitable. On the field, Mr. Christie behaved well; and when all was ready for the first fire, he called out – ‘Scott, you must not stand there; I see your head above the horizon; you give me an advantage.’ I believe he could have hit me then if he liked. After the pistols were reloaded, and everything was ready for a second fire, Mr. Trail called out—‘Now, Mr. Christie, take your aim, and do not throw away your advantage, as you did last time.’ I called out immediately, ‘What! did not Mr. Christie fire at me?’ I was answered by Mr. Pattmore—‘You must not speak; ‘tis now of no use to talk; you have nothing now for it but firing.’ The signal was immediately given, we fired, and I fell.” Deceased expressed himself satisfied with Mr. Christie’s conduct, whom he described as very kind to him after he was wounded.—Mr. T. J. Pettigrew, a surgeon, attended the duel professionally. It was a moonlight night, but foggy; he heard no conversation between the gentlemen prior to the discharge of the pistols; heard an exclamation after the discharge, and got over the hedge; found Mr. Scott on his knees. Mr. Christie asked him what he thought of the wound. He replied that he feared the wound was mortal. Mr. Scott then said, “whatever may be the issue of this case, I beg you all to bear in remembrance that everything has been fair and honourable.” Mr. Christie said, “Why was I permitted to fire a second time? I discharged my pistol down the field before, I could do no more.” These expressions were made in consequence of some altercation between the seconds. Mr. Christie took Mr. Scott by the hand after he was wounded. The jury returned a verdict of—Willful Murder against Mr. Christie, Mr. Trail, and Mr. Pattmore. The coroner issued his warrant for their apprehension.

[Transcription from The Examiner:] THE LATE DUEL.

The Court was crowded to excess, in consequence of the notification that the Gentlemen concerned in the unfortunate duel, in which the late Mr. Scott fell, would surrender to take their trials. At nine o’clock the Sheriffs entered the Court. At ten o’clock Lord Chief-Justice Abbott and Mr. Justice Park took their seats on the Bench.

Mr. Christie had previously entered the body of the Court, accompanied by his friend in the late unfortunate duel, Mr. Trail. Mr. Patmore, the friend of the deceased, did not make his appearance. None of the parties were bound over in recognizances. The two unfortunate Gentlemen were soon after ten o-clock put to the bar, and arraigned upon the indictment which charged them with the willful murder of John Scott, at Chalk Farm, on the 16th of February last. The prisoners pleaded Not Guilty, and put themselves for trial upon God and their Country.

They were dressed in black clothes, and seemed deeply impressed with the unfortunate situation in which they were placed.

Mr. WALFORD opened the case against them, and after entreating the Jury to dismiss from their minds all they had previously heard or read, respecting the melancholy event which led to the present trial, proceeded to detail the nature of the evidence which he had to adduce against the unfortunate Gentlemen at the bar. It would be superfluous to repeat the details of this evidence, as it was in substance the same as that which we have already published in our report of the evidence upon the Coroner’s Inquest.

The first witness was Mr. T. J. Pettigrew, who stated the particulars of the duel, and the declaration of Mr. Scott, after being wounded, that all was fair and honourable; and he described the agony of Mr. Christie, who exclaimed—“Good God! why was I permitted to fire a second time? I fired first down the field.”

He underwent a cross-examination by Mr. GURNEY, and repeated the extreme agony and anxiety of Mr. Christie for Mr. Scott’s situation.

Wm. Bevil Morris corroborated Mr. Pettigrew’s statement of what had occurred on the field; he also related Mr. Scott’s declaration that all was fair, the altercation between the seconds about the second fire, and Mr. Christie’s declaration of his wish that he was in Mr. Scott’s situation. At Mr. Pettigrew’s desire, he ran to have the post-chaise brought up the lane, ad on his return to the farm-house, he stopped and saw some persons bringing the deceased out of the field on a shutter. They carried him into the house, and he (witness) recognized the fair haired gentlemen (Mr. Christie) by Mr. Scott’s side. There were about four or five others, but he did not know them. . [proofed to here]

Hugh Watson was next examined.—He said he was landlord of the tavern at Chalk Farm; he remembered two gentlemen having had a bottle of wine in his house; he described the alarm of an accident which afterwards occurred, and the bringing in the wounded gentleman, accompanied by some others. The two gentlemen at the bar were among the number; when they came a second time they were assisting Mr. Scott, and the tall gentleman (Mr. Christie), went away.

James Ryan was hostler at the Chalk Farm Tavern; he remembered, on the Friday evening, some gentlemen having had a bottle of wine at his master’s; they stopped about twenty minutes, but he knew not who they were. He afterwards described the departure, and soon after the alarm of an accident in the field; he went forth, and found a wounded gentleman; he assisted to get him upon a shutter, with the assistance of four or five other gentlemen present, who came when he called them. They took the wounded gentleman into the house; he had no knowledge of the gentlemen who were present on the occasion.

Thomas Smith examined, and merely corroborated the last witness’s testimony.

Dr. George Darling was next examined.—He stated he was a physician reading in Brunswick-square. He was called in to attend the deceased by Mrs. Scott, in the middle of the Friday night, and communicated to him that his wound was of a very dangerous character, and that it was just possible his intestines might not have been perforated, and that then the danger was diminished, and a recovery possible; he afterwards inquired respecting his wound of Mr. Guthrie, the Surgeon, in witness’s presence, and his question was—“Is my wound necessarily mortal?” Mr. Guthrie answered, “Not necessarily” (this occurred before the ball was extracted), “but your case is of the greatest danger. I have, however, seen recoveries from similar wounds.” Mr. Scott then laid his head on the pillow, and said, “I am satisfied.” Mr. Scott then communicated to witness, at his visit on the following morning—

Chief Justice ABBOTT and Mr. Justice PARK here held a consultation upon the admissibility of the communication (whatever it was) which was made by Mr. Scott to Dr. Darling at a subsequent conversation, after the question respecting the effect of his wound, and the Learned Judges decided, the Doctor could not give in evidence Mr. Scott’s communication, it not appearing, as it should by law, to make it evidence, that the unfortunate Gentleman felt himself, when he made it, in articulo mortis—for he had been told that his wound was not necessarily mortal, unless the intestines were perforated.

Mr. WALFORD then closed the case for the prosecution.

Mr. GURNEY then left his seat at the table, and conversed for several minutes with the prisoners. After the Learned Counsel had left them.

The CHIEF JUSTICE addressed them severally, and said, the time had now arrived when they might, if they thought proper, address the Court in their defence.

Mr. Christie, with much evident emotion, replied to this communication, that he should call witnesses to show the Court that his character was free from my imputation of inhumanity and cruelty.

Mr. Trail replied, as well as we could collect what he said (for he spoke in a very low tone of voice), that he should make a similar reference to witnesses as to his character.

A number of witnesses then gave the prisoners a very high character for humanity and mildness of disposition.

Amongst them were several Clergymen, several Barristers, the Principle of Baliol College, Oxford, a number of students, and Mr. Balfour, the Member for Orkney; all of them spoke to a long and intimate knowledge of the prisoners.

Chief Justice ABBOTT (after consulting with Mr. Justice PARK) charged the Jury; and after laying down the law of the case, as applied to the present charge, enumerated the details of the evidence, and left it to the Jury to say whether there was sufficient proof to identify the prisoners at the bar with the occurrence which led to the mortal wound of the deceased. The Court also remarked, that the Jury had no proof how the fatal occurrence originated. If, however, they considered they had proof of their being two of the parties to the fatal act, the Jury had then to consider what sort of deliberation preceded the act, and how far it justified the full charge of preparation for committing it, which was indispensable in a case of Willful Murder. If the Jury thought there was that precipitancy in the occurrence which, making allowance for human frailty, took away the capital part of the charge, then it remained for them to say whether the minor parts of the charge were maintained, so as to constitute the crime of Manslaughter.

The Jury consulted about half an hour and returned a verdict of Not Guilty.