18 January 1818: Keats’s Triple-H: Hunt, Haydon, Hazlitt

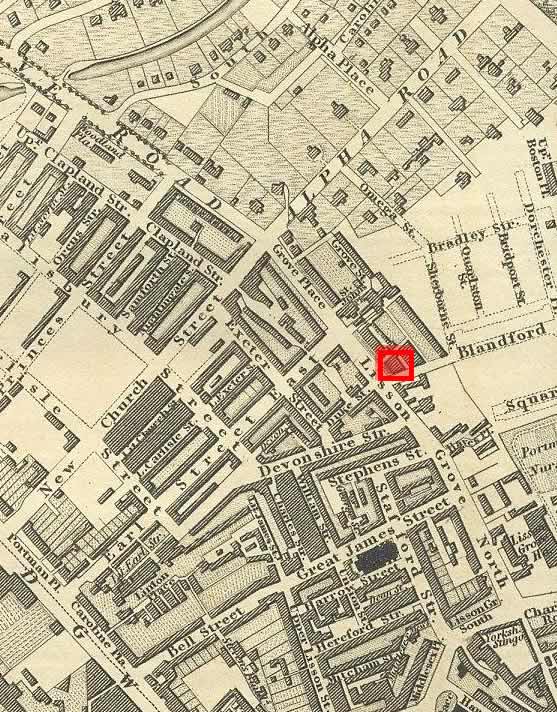

22 Lisson Grove North, London

22 Lisson Grove North is now No. 1, Rossmore Road

After spending time with his friend, the journalist, critic, and poet Leigh Hunt, on 18 January Keats dines at another friend’s residence, the noted historical artist Benjamin Robert Haydon. William Hazlitt (literary critic and lecturer) and William Bewick (Haydon’s student) are present. Keats at the moment is completing revisions and corrections to his long poem, Endymion, begun April 1817, with publication scheduled for April. Keats can hardly wait to put the poem behind him.

Given the knowledge, experience, and opinions of Keats’s Triple-H of influences—Hunt, Haydon, Hazlitt—social occasions like

these challenge and expand Keats’s ideas about art, propel his poetic progress, and

cast his

drive for independence. Keats is very much the junior member at such gatherings, in

not just

age but also experience and reputation. That Keats is frequently included in gatherings

of

established writers and artists attests to something about Keats’s qualities, to his

inherent

personal and poetical attributes. There is also a fourth H

within Keats’s closest

circle—William Haslam—who also comes to

Haydon’s this evening to dine.

With the pace of his socializing from December into January, Keats confesses he has

been

racketing [socializing, seeking entertainments] too much, & and does not feel over

well

(letters, 10 Jan 1818). It seems he does a fair amount of drinking this month, with

a special preference for claret.

Initially through Haydon, Keats seems to see

quite a bit of the great poet William

Wordsworth (an increasingly ambivalent figure for Keats) around this time, while his

friendship with Haydon may be at a high point. Haydon in a letter to Keats, 11 January,

writes

from my heart

about John Keats’ genius

as something to rejoice at.

Haydon confesses his devotion to and affection for Keats: My Friendship for you is beyond

its teens, & beginning to ripen to maturity.

Keats is not quite as forthcoming,

though he greatly admires Haydon’s paintings—or, maybe more, Haydon’s devotion to

art. But

truth be known, Haydon’s paintings, though grand in topic and scale, and fairly decent

in

execution, are largely void of imaginative or innovative qualities. Haydon is also

notoriously

slow—and notoriously temperamental.

Crucially, in terms of his poetic development, on 23 January, Keats notes to Haydon that, in thinking through a new, Miltonic

project— Hyperion—he will leave behind the many bits of the

deep and sentimental cast

in Endymion, and instead now

approach his subject in a more naked and grecian Manner—and the march of passion and

endeavor will be undeviating.

In writing to his brothers on the same day, he notes a

little change has taken place in my intellect lately. [. . .] Nothing is finer for

the

purposes of great productions than a very gradual ripening of the intellectual powers.

[. .

.] So you see I am getting at it, with a sort of determination and strength . . .

. In

writing this, we detect in Keats that he sees a way forward from his previous significant

poetic deficiencies—the Huntian ornamental and somewhat random qualities—of Endymion and the 1817 collection. The Hyperion project (in two

significant starts) will never be completed, despite its advanced elevated tone and

mature

poetic countenance. Some of Keats’s changing views of literary quality and qualities

are

beginning to spin off from his contact with and reading of Hazlitt.

It is less than about a month since Keats has begun to strongly articulate a poetics that, put in practice by the end of 1818 and into early 1819, results in poetry quite unlike his earlier verse. We will thus find that his mature poetic voice employs a style and voice unobtrusively immersed within the subject, with masterfully measured intensity in approaching and encasing his subjects. Importantly, Keats will also use a form, mainly lyrical and shaped by his innovative application of the sonnet with an odal form, and where sound syncs with meaning and does not distract. As mentioned, the opposite happens in Endymion, where couplets and capricious description both bog down and randomize the poem’s sense and direction.