12 January 1818: A Night on the Town: from John Bull to Richard III to Gradual Ripening

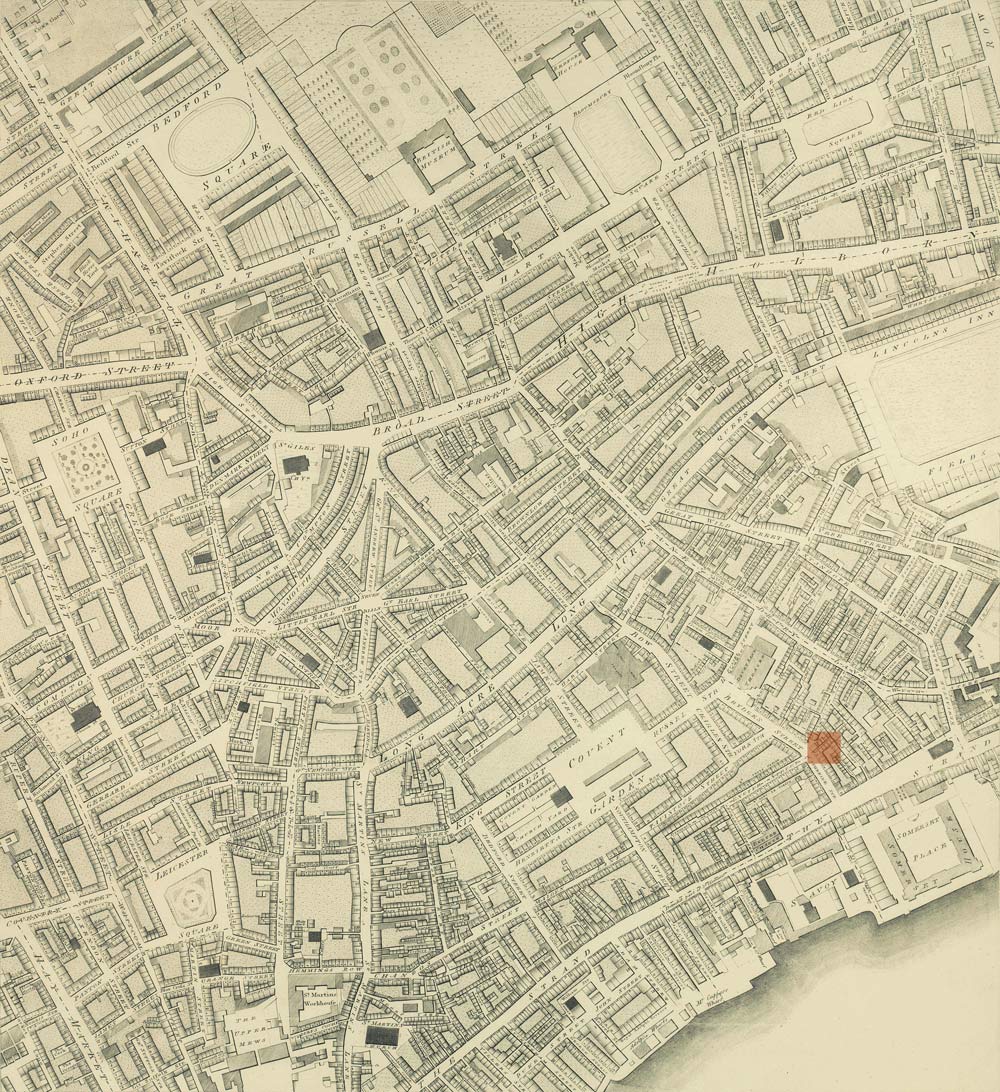

The Minor Theatre, Catherine Street, London

Keats goes to this private and mainly amateur theatre with his friend, Charles Wells, to see George Colman’s John Bull; or, The Englishman’s Fireside. (The Minor Theatre was also known as the Harmonic Theatre in 1816; Colman, a fairly controversial figure, writes mainly comedic drama and some poetry; the play was originally produced in 1803.) The play is, for them, so bad that after watching only a bit of it they leave to see Shakespeare’s Richard III (with Edmund Kean in the title role) over at Drury Lane. They then return to The Minor to check out the intriguing and uproarious backstage atmosphere, and retire to a nearby inn and take some delight in observing the actors’ pompous yet carefree manner.

Keats is extraordinarily social at this moment, calling on friends and going to breakfasts,

dinners, dances, and the theatre; in fact, he reports that he is fatigued by so much

socializing (letter, to John Taylor, 10 Jan).

Interestingly, his personality allows him to endure and detach himself from the faults

and

petty grievances of his very closest friends, including Leigh Hunt, Benjamin Robert Haydon,

and John Hamilton Reynolds. In a letter to his

brothers, Keats describes their tiffs, ranging from broken social engagements to unreturned

silverware (13/19 January). Keats’s attitude in accepting the complexities, inconsistencies,

and faults of his friends might be connected to his more philosophical acceptance

of

uncertainty and doubt as moments of capability rather than rejection. Keats, though,

doesn’t

mind a little gushing mutual admiration from Haydon, who writes to Keats on 11 January

that

their Age

should be proud of John Keats’ genius!

Haydon goes on to say

that he speaks this from my heart,

and that he will always consider himself Keats’s

devoted & affectionate Brother.

By the end of the year, their relationship is a

little strained over money issues—both need some, and neither has much.

Meanwhile, and crucially, Keats also sees that his very long poem, Endymion, now under final revision before publication, lacks depth and formal powers, and he contemplates something like a more Miltonic tone and scope in his poetry. Keats is keen to put Endymion—a self-imposed endurance test—behind him. In a week or so, he will deliver a corrected copy of Book I to his publishers.

In light of conversations with his many friends and acquaintances in the writing,

publishing, and art scene, ranging from the minor Wells to the major Wordsworth, and

with his very deliberate drive to study poetry as much as write it, Keats at the beginning

of

1818 is beginning to carve out his own poetics and poetical character. In hindsight

we see how

this drive for independence remarkably anticipates the qualities and nature of his

greatest

poetry, almost exclusively that of 1819. In short, his intense poetics precedes his

greatest

poetry. Later in the month, Keats implicitly comments upon his own development: Nothing is

finer for the purposes of great productions, than the very gradual ripening of the

intellectual powers

(letters, 23/24 Jan). Keats believes that (at least at this moment,

and inspired by King Lear) I am getting at it, with a sort

of determination and strength.

For us, though, the very gradual ripening

does not

look that gradual at all. Keats goes from writing astonishingly bad poetry to writing

astonishing poetry over just a couple of years—and in his early twenties. Again, Keats’s

flurries of remarkable commentary about the qualities of great poetry throughout 1818

both

anticipate and propel his flurry of great poetry in 1819.