19 October 1816: A Crucial Moment: Meeting Leigh Hunt & the London Scene

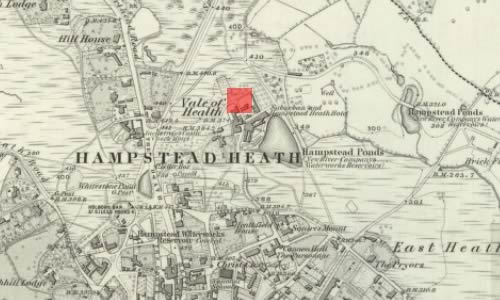

The Vale of Health, Hampstead

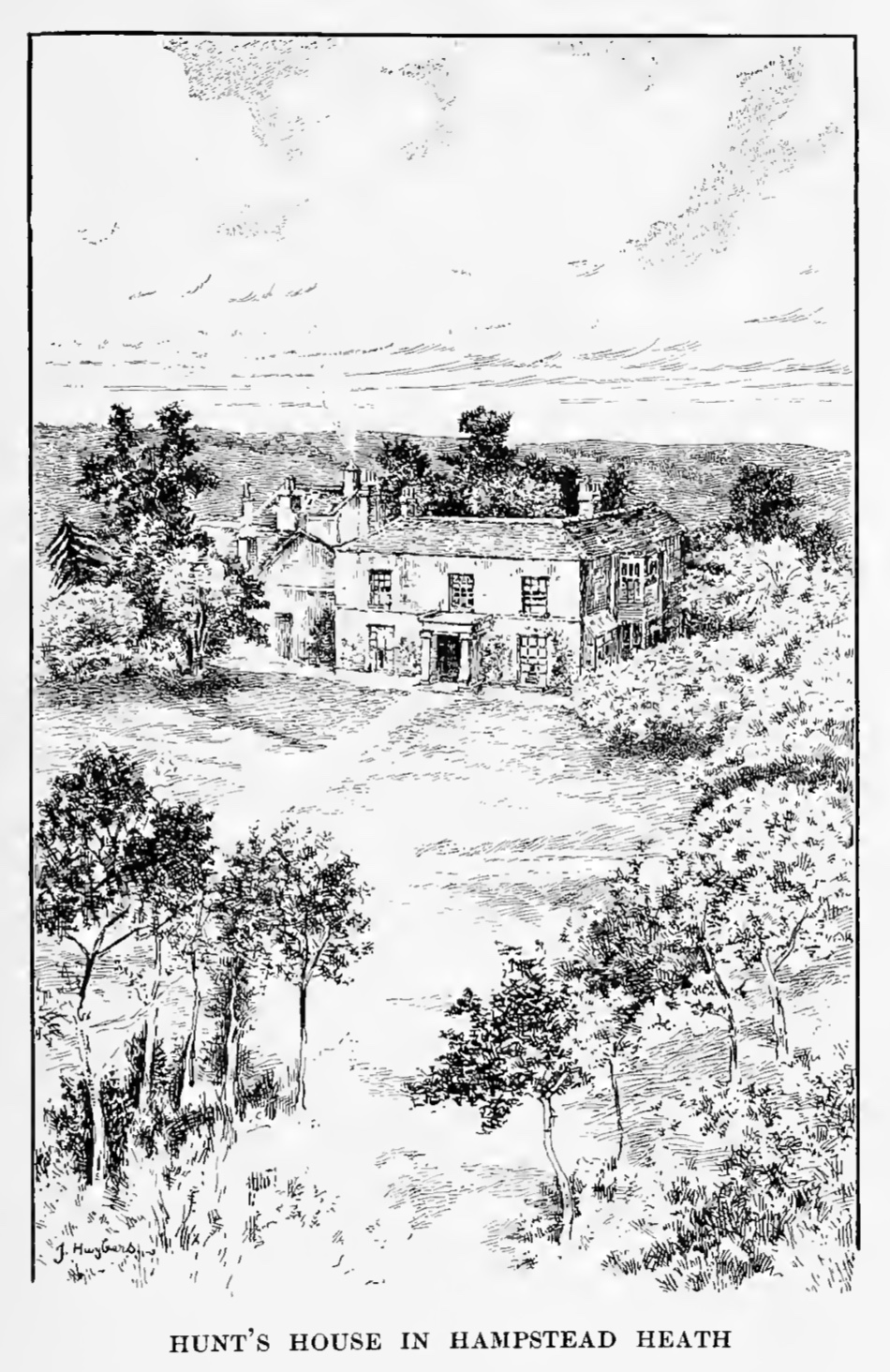

Leigh Hunt’s fairly small cottage in the Vale of Health, Hampstead, where, with his ever-growing family, Hunt has lived since the end of 1815.

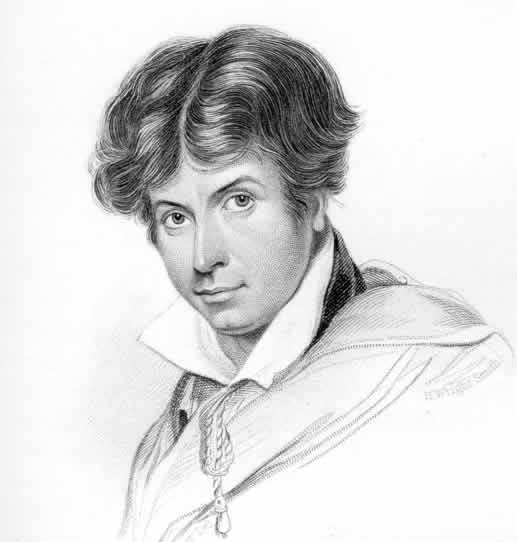

On or about 19 October 1816—Hunt’s birthday—the crucial meeting takes place: twenty-year-old Keats gets to see the famous and controversial Hunt (free-thinking journalist, poet, critic, publisher) at Hunt’s cottage. That is, we have to keep in mind the relational circumstance: Keats, a nobody, meets Hunt, a somebody. Moreover, that somebody is a hero for that nobody.

The meeting takes place through their mutual friend, Charles Cowden Clarke, the son of Keats’s headmaster at Enfield school, and the

first person to fairly deliberately shape Keats’s literary tastes. Clarke records

that, for

Keats, the visit to see Hunt is a red-letter day.

It won’t be long before Keats finds

himself sleeping over at Hunt’s, where, quite naturally, he rapidly absorbs Hunt’s

lifestyle

and cultural milieu. [See here for a graph of Keats’s social

network to see the important placment of Clarke and Hunt.]

The back-story in brief: Clarke has previously shown Hunt—and Horace Smith—a couple of Keats’s poems, and, being impressed by the poetry, Hunt suggests Clarke bring the young poet over; thus Hunt has been primed by knowing some of Keats’s work. And on Keats’s part, much earlier in the year, Keats has written poetry praising Hunt’s and poems modelling his poetic style (see On The Story of Rimini, Calidore, Specimen of an Induction to a Poem).

Importantly, via Hunt, Keats almost immediately meets Benjamin Robert Haydon, the noted historical painter, who has been staying in Hampstead and spending quite a bit of time with Hunt. Keats breakfasts with Haydon 3 November; Haydon quickly becomes a devoted friend and supporter of Keats, and, at least early on, Keats greatly venerates Haydon—they see each other as kindred, creative spirits, which is somewhat remarkable given how very little Keats has thus far done; Haydon must have perceived something, or else he just needs a young fan. Keats also meets aspiring and published poet John Hamilton Reynolds via Hunt, and Reynolds in turn introduces Keats to a number of people who become friends and supporters.

In short, connection with Hunt immediately throws the young, unknown, and inexperienced Keats into a particular but significant part of the London literary and artistic intelligentsia—generally, those on the liberal-reformist side of issues: poets, critics, journalists, publishers, playwrights, artists, and so on. It is a coterie of sorts, but not necessarily in a exclusive sense—the range of interests, values, and beliefs are sprawling. But the bottom line remains: Keats is profitably thrown into this mix, and this early grouping—Hunt, Haydon, and Reynolds in particular—thus becomes the foundation for Keats’s poetic progress. Clarke, in a way, gets left behind.

On 2 December 1816, Hunt includes Keats (along

with Percy Shelley and Reynolds) as belonging to a new school of poetry.

Appearing in Hunt’s journal—The Examiner—announces Keats’s

affiliations, as does Keats’s very first publication (O Solitude), on 5 May 1816, also in Hunt’s

Examiner. Association with Hunt will later directly lead

to some cutting, dismissive critiques of Keats’s early poetry (and equally rough personal

treatment) by Tory reviewers; more specifically, Keats will become dismissively affiliated

with the so-called Cockney School of Poetry,

in attacks mainly motivated by political

and viscous personal attacks on Hunt. Nevertheless, in Keats’s case, these reviewers

are

generally correct in finding certain faults in Keats’s early poetry—it is plagued

by affected

jargon and random purpose; too often costume trumps substance. But we should not be

surprised

that Keats’s earliest work too easily parades his inexperience and overworked longings;

looking back a little, Keats himself will have little problem acknowledging his poetic

immaturity and missteps: by 1820, he can look back and call his early poetry my first

blights

(letters, 16 Aug 1820).

Through people like Haydon and Reynolds, Keats’s intellectual network expands even

further. For example, by the end of 1816, Haydon has in fact sent a copy of Keats’s

sonnet

Great

Spirits to the preeminent poet of the age, William Wordsworth. Keats writes to Haydon on 21 November,

The Idea of your sending it to Wordsworth put me out of breath.

Wordsworth, typically

reserved, found the sonnet promising and agreeable. Over the next few years, Keats

will in

fact spend significant energies coming to terms with both Wordsworth’s poetic powers

and

limitations. Keats meets with Wordsworth a number of times in late 1817 and into early

1818.

[For more on Keats’s meeting with Wordsworth, see 16 December

1817 and 5 January 1818.]

As mentioned, this network that grows out of Keats’s meeting with Hunt is absolutely crucial to Keats’s poetic progress, though, within a year, Keats’s early enthusiasms with Hunt begin to wane as he attempts to shape and develop his own poetic identity. And both Haydon and Reynold will play a part in moving Keats away from Hunt’s poetic sway, even if Hunt’s reformist, independent, and free-thinking views remain part of Keats’s natural political sympathies—in fact, they were largely fixed before he even met Hunt. [For more about Keats’s complex and changing attitude toward Hunt, see 6 March 1818.]

To express this longer narrative in a slightly different way: In connecting with and

then

being promoted by Hunt, Keats finds himself the middle of a kind of culture war over

not just

poetic legitimacy, but the politics of poetic legitimacy as debated within his era.

Initially, this does not matter so much for Keats, and initially he continues to compose

a

version of the liberal-suburban poetry of sociability often associated with Hunt.

But, as

suggested above, within a year, and as Keats purposefully begins to formulate and

express a

sense of his own goals, sensibilities, and unique qualities, he begins to set his

poetic

ambitions much beyond such a limiting context and style; and within a few more years,

and by

about the second half of 1818, he actually produces poetry that he hopes goes beyond

partisan

squabbles over poetic legitimacy. Of course, artistic production can never escape

its meaning

associated with its originating material history (some types of criticism will see

to that),

but Keats will make it clear he has a greater, more enduring poetic tradition in mind

as he

evolves his extraordinary thinking about the poetical character.* When a few very

nasty

attacks do come Keats’s way (and he expected them), he sees them as a mere matter of the

moment

(letters, 12 Oct 1818); he’s thinking bigger, and far beyond the moment.

*For more about Keats’s conception of the poetical character, go to 14-31 October 1818: Caring for Tom, his Poetical Character, and Being Among the English Poets.