6 March 1818: Endymion: A Trial of Perseverance; or, Mistakes are Opportunities for Learning; To Teignmouth; the Keats/Hunt Relationship

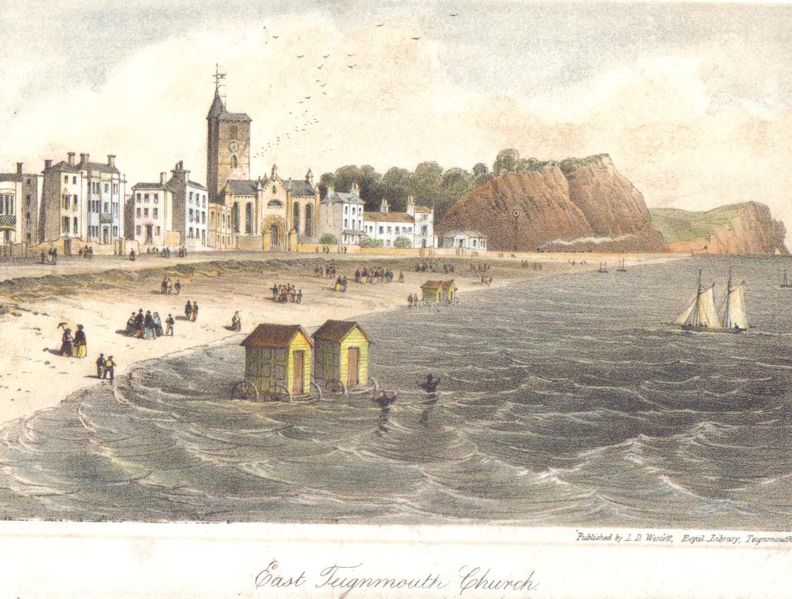

Exeter to Teignmouth

Via Exeter, and running into a severe storm that hinders travel, Keats leaves for Teignmouth from London on 4 March. Keats apparently travels on the outside of the coach, which would have been cheaper seating but, in bad weather, very nasty. Keats gets to Exeter on 6 March.

Keats, aged 22, is on his way to visit his brother, Tom, aged 18, who is quite ill with consumption. Keats is in a way relieving his other younger brother, George, who has been taking care of Tom. Keats also hopes to get some work done as well as enjoy the countryside. Sadly, Tom has become a huge burden, both for Keats and George. This only increases over the coming months. Before the end of the year, on 1 December, with Keats beside him and George in America, Tom passes away, aged 19. Keats stays at Teignmouth for just under two months, and he is back in Hampstead by about the end of the first week of May.

By the middle of March, Keats has copied out the fourth and final book of his long

poem,

Endymion, which

he began in April 1817. He sees the poem as a test or trial of his inventive and imaginative

powers; as an exercise of perseverance he felt, at least initially, it might prove

his

dedication to poetry and earn him the title of poet. After compling the poem, his

enthusiasm

for the project slumps, though he wants to believe that even failure represents some

kind of

progress. Before even arriving at Teignmouth, Keats’s desire to move forward is very

clear:

I am anxious to get Endymion printed that I may forget it and proceed

(27 Feb 1818). This is

terrific self-advice. And how deliberate it sounds!

Keats submits a corrected, final draft of Endymion for his

publishers (Taylor & Hessey) by 14 March. He struggles with a preface for the poem: awkwardly

pressured by his publishers and a friend (John

Hamilton Reynolds), he revises the preface. Nevertheless, in its admission of great

faults and immaturity, the final version opens Keats and his poem up to public criticism

from

some quarters of the divisive Regency culture wars, which boiled down to politics

and class.

Endymion, Keats

declares in the preface, is a feverish attempt, rather than a deed accomplished.

He is

right, and he’s not being coy. At one point, Keats at a fairly

impressive dinner party suggests to an acquaintance—Joseph Richie, who is about to go

off to explore Africa—that he take Endymion with him and toss it into the

middle of the Sahara desert, presumably to be lost forever, covered by the sands of

time.

Because of Endymion’s advertised shortcomings of its sandy

foundations and Keats’s obvious association with a certain kind of poetry revolving

around

Leigh Hunt (the poetry of fancy and sociability,

of occasion and suburbanized recreation), it is clear that Keats increasingly desires

to carve

out his own independent position, especially relative to what he feels is Hunt’s inflated sense of his own poetic accomplishment (to Haydon, 21 March). Keats has already confessed to

one of his publishers, John Taylor, that Endymion is a Pioneer

of sorts, that his new poetical

Axioms

will be that poetry display fine excess,

implying that the Huntian

model luxuriates too much in its excesses. As he progresses, Keats aims for a tone

and style

that will appear content, emerge naturally, and assume a sober, stilled, and yet intense

hold

over both the subject and the reader—all the things, that is, that most of Endymion does not do

(27 Feb 1818); it remains a poem riddled by pushy, incongruous rhymes and muddled

in

meandering plot—at best, for the reader, it represents diversionary pleasantries worthy

of a

bit of wandering.

Although Keats’s long, imperfect poem begins with a perfect line that perfectly captures

his

developing poetic credo—A thing of beauty is a joy forever

—and although the opening

passage fluently expresses how lasting beauty in nature and literature can counter

and lift

the pall / From our dark spirits,

the bulk of the poem is aesthetically unconvincing.

It is, in short, hardly a joy forever

—though the poem seems to go on forever—and Keats

knows this. As mentioned, in the poem’s preface, Keats is a good-enough and honest-enough

critic to rightly point to its sandy foundations and its mawkish, thick-sighted ambitions.

Because of its bulk and because it is narrative driven, it is even more random and

ineffectual

than, say, his earlier longish I stood tip-toe; but, as in

the tip-toe poem, there is little to block those jingling couplets or jam over-employed

enjambment. At least in the earlier poem, the young poet seems to be having a little

fun in

haphazardly pointing to all the flora and fauna, and in imagining the wonderful human

sources

of mythology. But the poem’s slapdash direction and purpose can be represented by

an almost

laughable line: after noting laburnum, wildbriar, violets, a youngling tree

(ouch!),

a streamlet’s rushy banks

(double ouch!), blue bells, woodbine, sweet peas, skittish

minnows, goldfinches, as well the imagined presence of an alluring, auburn-haired,

nimble-toed

maiden, Keats writes, What next?

(29-106). Indeed! Endymion, by comparison, reads more like

a job carried with a determined rather than inspired sub-text: How do I keep this poem

going?

Just some seven or so years after Keats’s death, in his essay on Keats in Lord Byron and

some of his Contemporaries, Hunt himself comments fairly harshly, but with some

critical insight, on the untamed stylistic and tonal misreckonings of Endymion. The poem, Hunt writes, is

not a little calculated to perplex the critics. It was a wilderness of sweets, but

it was

truly a wilderness; a domain of young, luxuriant, uncompromising poetry.

Besides its

unpruned luxuriance,

Hunt at length specifically points to the willfulness of its

rhymes. The author had a just contempt for the monotonous termination of every-day

couplets;

he broke up his lines in order to distribute the rhyme properly; but going only upon

the

ground of his contempt, and not having yet settled with himself any principle of

versification, the very exuberance of his ideas led him to make use of the first rhymes

that

offered; so that, by a new meeting of extremes, the effect was as artificial, and

much more

obtrusive than the one under the old system. Dryden modestly confessed, that a rhyme

had

often helped him to a thought. Mr. Keats, in the tyranny of his wealth, forced his

rhymes to

help him, whether they would or not; and they obeyed him, in the most singular manner,

with

equal promptitude and ungainness.

Rhyme, it seems, trumps reason; sound forces sense;

the artificial overrides the art. So says Hunt.

There is some ironic complexity in Hunt’s above commentary, given that his own poetry

often

falls into these characteristics, and Keats, at least initially, follows them. This

dates at

least as far back as Hunt’s controversial 1816 long poem, The Story of Rimini, which,

too often and often awkwardly, moves between the transgressive and the decorative,

with some

dips into pathos despite its modern idiom; the dramatic and the descriptive are sometimes

jumbled, with the latter often interrupting the former; and like Keats’s long romance,

it too

reads like an exercise in endurance. However, some criticism also points to the methodless

style of Hunt’s poem, to its lax and lawless versification

(The British Critic, and

London Critical Journal for May 1816); a few years later, in the August 1818 issues of

Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, Keats in Endymion will be accused of adopting the

loose, nerveless versification

of Hunt’s Rimini. These two echoing

charges—lax and lawless versification,

loose, nerveless versification

—pretty well summarize Hunt’s criticism of Endymion. Thus we are

presented with a strangely recursive chronology: Hunt is criticized for his versification;

Keats is criticized for versification that follows Hunt’s; and Hunt criticizes Keats’s

versification that is much like his own. This complicating story has something else

thrown

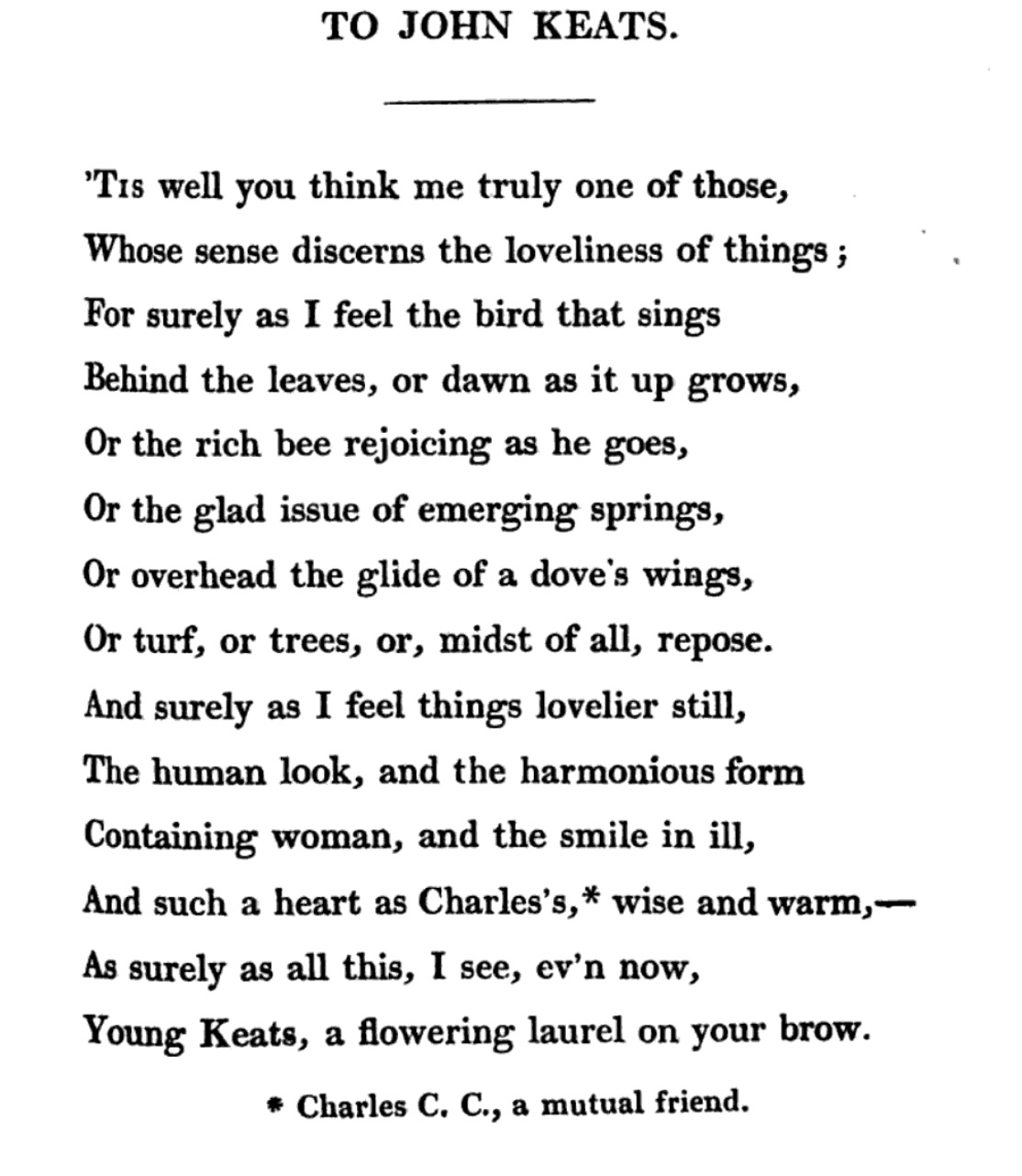

into the middle of it: Hunt’s 1818 collection, Foliage, which contains a sonnet to

Keats that is really about Hunt’s own superior poetic sensibilities, is privately

disparaged

by as Keats as being pretentious.

To John Keatsas published in Foliage (1818) Click to enlarge.

And there is an added and intersecting layer of complexity, but it clarifies Keats’s

progress

relative to his connection to and relationship with Hunt. Back in February 1816, Hunt

publishes The Story of Rimini; about a year later, Keats in March 1817 sonnet

celebrates Hunt’s sweet tale

—On The Story of

Rimini—and how, armed with its charm, one can be steered to the delicate

delights of nature. Keats earlier has already soaked up some of this sentiment and

Hunt’s

loose heroic couplets in early 1816 poems like Calidore and Specimen of an Induction to a

Poem, which, into later 1816, are carried through into I stood tip-toe and

Sleep and

Poetry; and then, by April 1817, into the composition of Endymion. But, for Keats, a month or

so later, in May 1817, some of the gloss has come off Hunt: Keats is worked up by

Hunt’s

self-delusion in thinking himself a great poet (11 May); by October 1817, with worries

over

having an independent voice, Keats is right to believe that Hunt’s presence will be

read into

Endymion (8 Oct 1817). By the end of the year, Keats shrugs at how Hunt, in his

writing, unprofitably mixes egotism with opinion (21 Dec 1817). Into early 1818, after

saying

that we should hate poetry that has a palpable design upon us,

Keats declares he will

have no more of Hunt (3 Feb 1818). By mid-June 1818, Keats can claim that his public

poetic

identity is smothered

by identification with Hunt’s poetry (18 June, to Bailey); that is true enough, and is noticed by both

friend and foe. By the end of 1818, Keats lets it all out, and claims that Hunt is vain,

egotistical and disgusting in matters of taste and in moral,

and he goes on to strongly

condemn how Hunt is harmful by making fine things petty and beautiful things hateful

(17 Dec 1818).

Well, this is a potted chronology of a young poet establishing his own authority relative

to

another authority—knotted by personal relationship. But in the end, when Keats’s poetry

has

risen far beyond Endymion via his 1820 collection, and while at the same time he sinks toward the

horrors of consumption mid-1820, he gathers his dignity and strength to rise above

doubts

about Hunt; he recognizes Hunt’s kindness and generosity, given that Hunt (himself

not well)

and his wife take care of Keats for more than six weeks, over June into August 1820,

when

Keats’s haemorrhaging is dreadfully severe. He will write to Hunt, I feel really attached

to you for your many sympathies, and patience with my lunes.

On Hunt’s part, his 1820

translation of Tasso’s Amyntas, A Tale of the Woods is affectionately dedicated to

Keats, and suggests a connection between Keats and Tasso.

And the larger questions in Keats’s narrative: Without Hunt and Hunt’s connections, without Hunt’s early encouragements, and without Keats’s anxiety of influence concerning Hunt’s poetry and poetics, would Keats have continued on his poetic path as we know it—would he have developed that highly sought-after original voice?

But finally, back to the versification

issue from a different angle: at work on

perhaps a somewhat subversive level is Keats’s deliberate use of those enjambed, unconstrained

couplets, which literally sounds a challenge to the closed (end-stopped) or Augustan

couplet

(mainly represented by reigning champion of such poetry, Alexander Pope). And as we

have seen,

Hunt, too, had the same accusations thrown at him that he throws at Keats; Hunt, though,

perhaps even more than Keats, was fully used that the stylistic practice—those unenclosed

heroic couplets—to provocatively confront accepted poetic practice that privileges

regularity,

order, and those old rules that somehow reflect harmony and aesthetic grace. Thus

it could be

argued that Keats’s formal practice affronts—perhaps purposefully, perhaps because

of

aesthetic choice—some tastes that are directed by cultural and, ultimately, political

principles. How dare Keats, following Hunt, question not just neoclassical tastes,

but also

conservative values! And no wonder some Tory reviewers will line up to condemn Keats

and his

too-liberal verses, to be known and condemned as the Cockney school

of both poetry and

politics, with Hunt nominated as the headmaster. Arguments about taste do often make

their way

through judgements, into beliefs, over to values, and then, into politics. What Keats

at this

point so purposefully subversive, or just following the more liberal fashion of

versification?