27 October 1816: The Intellectual Network & Haydon

Pond Street, Hampstead

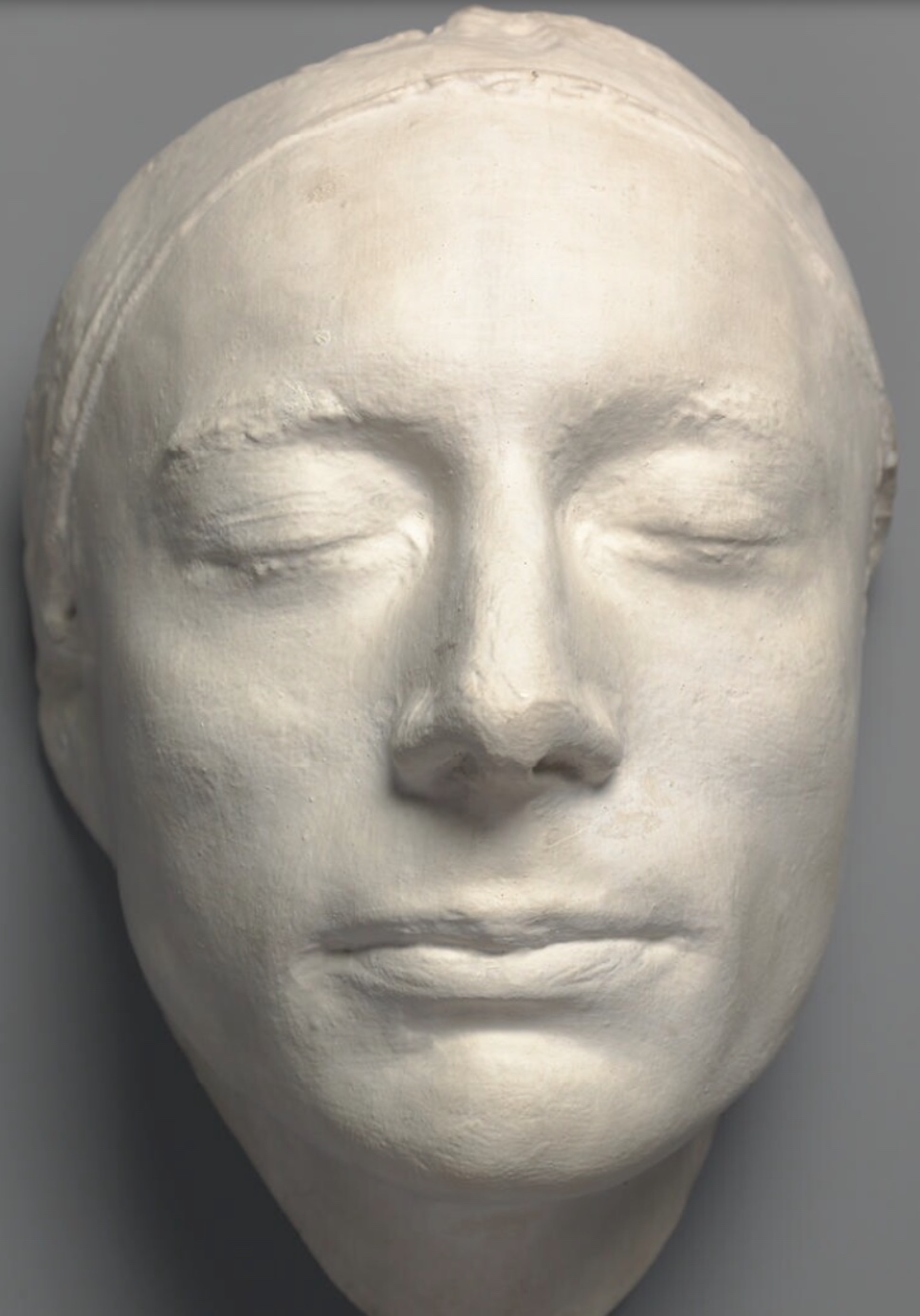

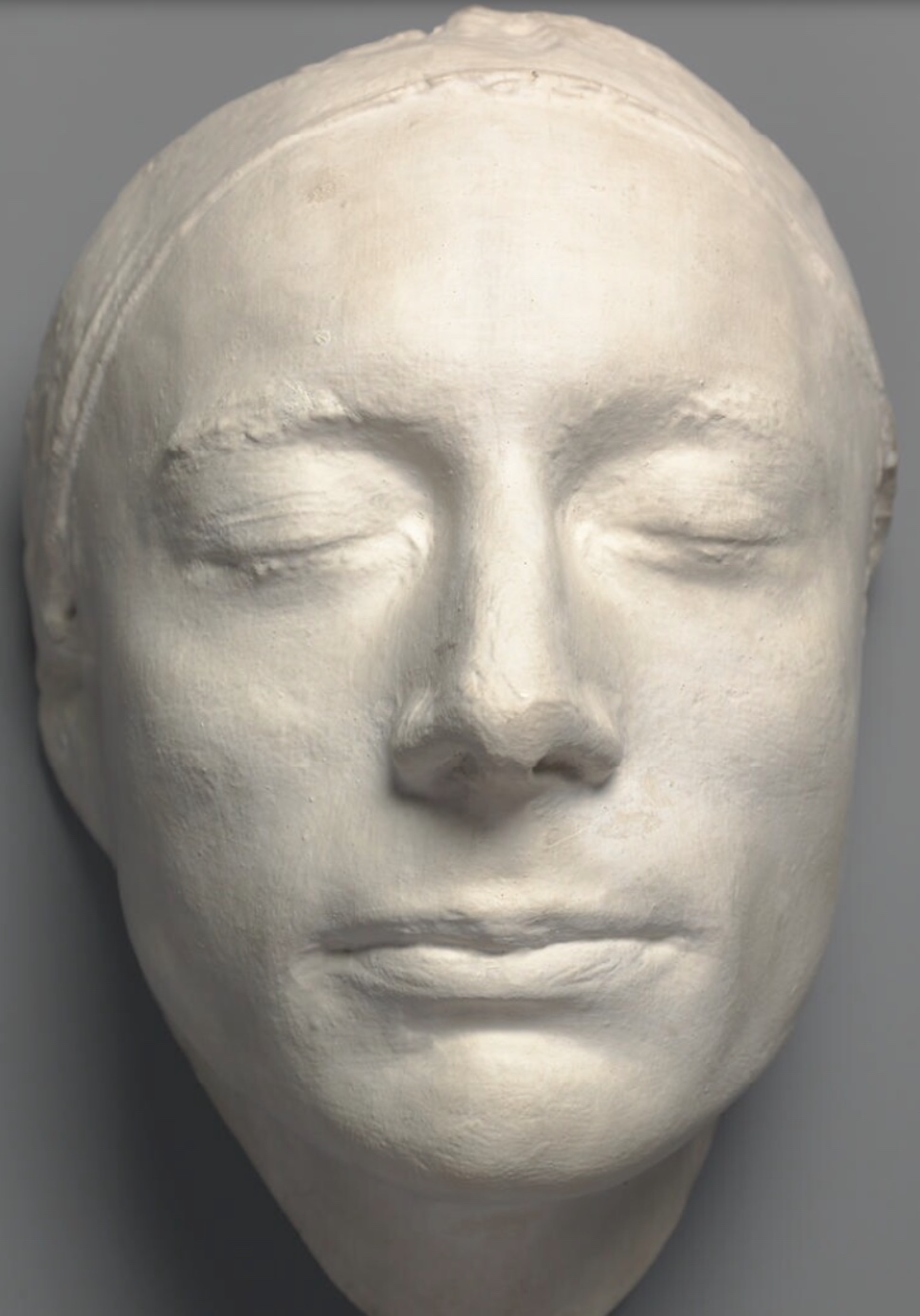

7 Pond Street, Hampstead: Where Benjamin Robert Haydon, the well-known historical painter, temporarily lives, apparently because of eye troubles, which he attempts to remedy by rest. Keats, twenty years old, has just met Haydon through poet, critic, and celebrity journalist Leigh Hunt. After an initial meeting or two, on 27 October 1816, Keats lunches with Haydon. About a week later, Keats breakfasts with him at his studio, and according to Haydon, Keats from this point has an open invitation to visit Haydon. Some time in early December, Haydon will make a life-mask of Keats, which has become an iconic representation of Keats.

The relationship between Haydon and Keats (Haydon is almost 10 years Keats’s senior)

is

highly enthusiastic and takes very little time to become emotionally charged with

feelings of

mutual support and praise. By March 1817, Haydon is capable of signing off a letter

to Keats

with the words, let our hearts be buried in each other,

and on 8 May 1817, ever

& ever yours.

And by 10/11 May, Keats is certain that Haydon loves him like a

brother, and that Haydon understands Keats’s own turmoil and anxiety

better than anyone

else. Haydon, though, will later prove to be somewhat combative and touchy with some

of

Keats’s other friends, as well as plagued by other personal and professional difficulties.

Haydon’s is one of the first of many important relationships that begin to form, expand, and challenge Keats’s ideas about art and poetry—and the qualities of the poetic character. Haydon—a deep poetry lover—is extraordinarily supportive and, now and then, protective of Keats. Haydon believes the two are linked by unacknowledged genius and destined greatness; Keats, at least, is a little more humble, though, via Hunt as well, the idea of fame confuses his larger poetic goals. But we have to get close to this moment, and to imagine how young, unknown Keats must have felt being touted so strongly by the older, more famous figure, who was well known as passionate public defender of great art. Contact with Haydon no doubt propels Keats’s early poetic ambitions, and Haydon’s views and knowledge about art—including poetry—fuel Keats’s aspirations. [See Keats’s social network, which shows the important placement of Haydon.]

Keats, then, has to be more than excited about meeting such persons as Hunt, Haydon, and young poet John Hamilton Reynolds, who, between them, know many of the other important literary figures of the age, including William Godwin, William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Lord Byron, as well as arbiters of taste, like William Hazlitt, not to mention a host of other writers, publishers, and artists. This constitutes the important intellectual and social network essential to who and what will influence Keats’s poetry.

Keats’s excitement—awe, even—over his growing associations is expressed in his sonnet

Great Spirits,

written 20 November, which, in highly praising the cultural distinctions of Wordsworth,

Hunt,

and Haydon) is a follow-up to another sonnet, Addressed to Haydon, which bows to Haydon’s gallant work and

stedfast genius.

Keats has not quite picked up on Haydon’s

competition with Hunt over the attentions of Keats

and Reynolds, though Keats later discovers

this. (Reynolds, by November, is, like Keats, smitten by Haydon, and he writes a gushing

sonnet to him, which places the majestical,

immortal, sweet, radiant genius of Haydon

beside that of Michelangelo and Raphael.) And there is another young poet falling

into this

circle and into Hunt’s favor, a certain Percy Bysshe

Shelley, whose poetic aspirations rival those of Keats. Neither Keats nor Shelley has

any idea that literary history will pair the two.

Fairly early on in their relationship, Haydon warns Keats off Hunt’s influence, which

may not

be a bad thing in terms Keats’s poetic progress. Haydon, often put off by Hunt, will

later in

his autobiography refer to the group around Hunt as the Examiner clique,

a gathering

who, according to Haydon, spend a lot of their energies puffing each other up. Of

course this

sounds somewhat resentful and suggests a certain lack of self-awareness: Haydon himself

thrived on praise, and when he didn’t get it, he was capable of fairly openly praising

himself

while condemning those who don’t recognize his achievements. It also shows that Haydon

is, as

they say, on the outs with much of Hunt’s circle.

About a year later, and in a moment when Haydon’s quarrelsome nature surfaces, Keats

will

recall that it only took him about three days after first meeting Haydon to get enough of

his character

to not be surprised by his uneven conduct (letters, 22 Nov 1817); however,

the friendship continues, though at moments it is taxed. And by early 1818, Keats

takes a

little glee in giving an account of overblown quarrels that stroppy Haydon has over

things

like unacknowledged invitations and unreturned silverware (letters, 13/19 Jan 1818).

Keats,

though, will generally view Haydon as one who has been my true friend

(letters, 20 Dec

1818). But in the end, money issues (borrowing, lending) will partially compromise

the

relationship between the two; this comes to a head mid-June 1819, when Keats tells

Haydon that

he needs money more than Haydon does, and he asks Haydon to return a loan he made

to him

earlier in the year: Do borrow or beg some how what you can for me

(letters, 17 June

1819). Passion for art bring Haydon and Keats together; money trouble pulls them apart.

Haydon, in remembering Keats after his death, recalls him as someone possessing utter belief in his higher calling as a poet; that Keats eventually comes to bow to the influence and importance of Milton and Shakespeare; and that he was gentle, unselfish, and personable, though also at times resentful and haughty. Haydon also eventually perpetuates the myth that Keats’s failing health and despondency is the result of the nasty, partisan treatment he receives from a few contemporary critics. Some of this is projection. Haydon himself is extremely touchy about how he himself is treated by the some of London’s artistic circles—the two are, in effect, fellow victims, at least through Haydon’s eyes.