Keats’s Poetic Development: Some Key Factors & Keats’s Greater Conversation

Fine Judgement

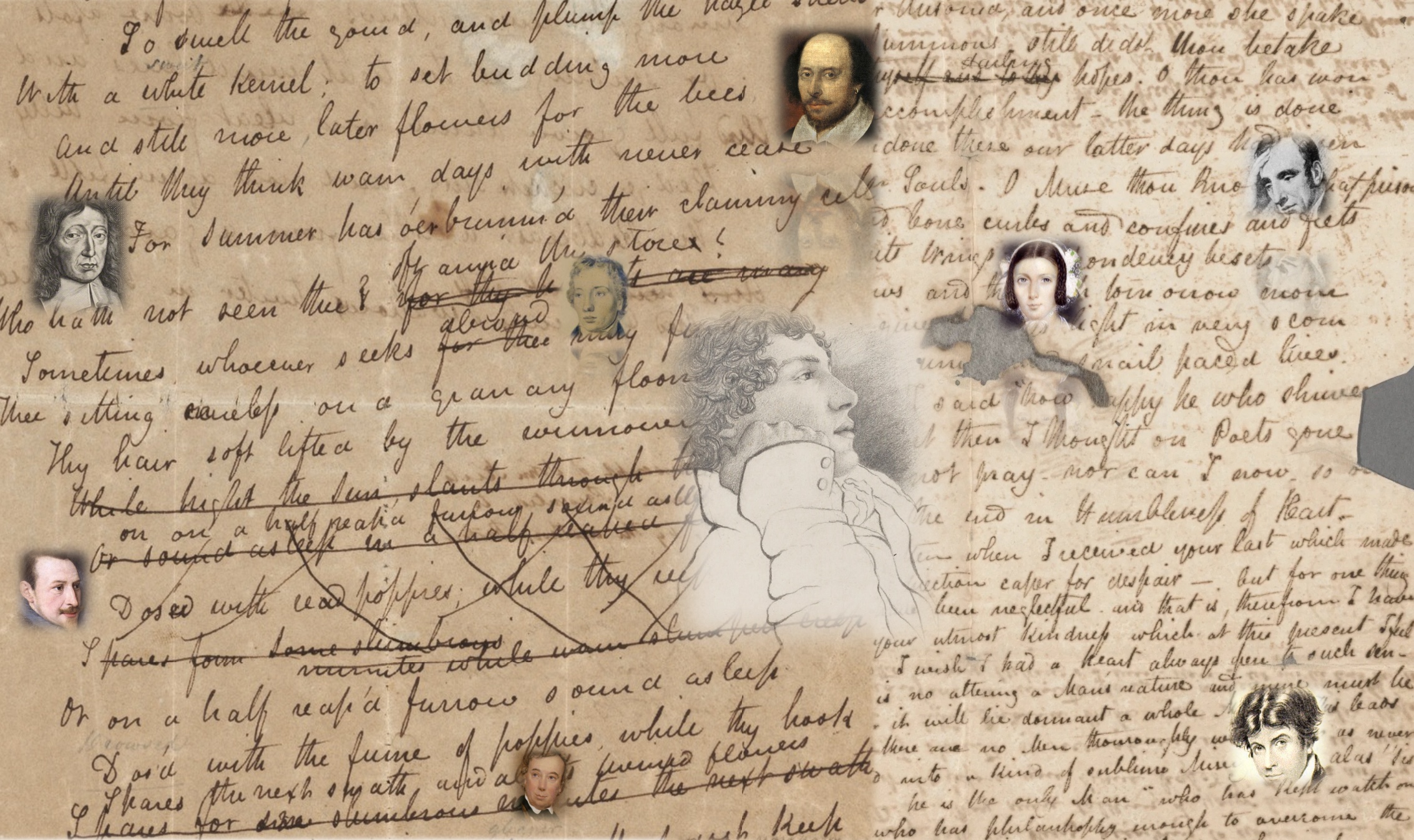

To Autumn,letter to Bailey, Spenser, Milton, Clarke, Tom Keats, Shakespeare, Fanny Brawne, Hunt, Wordsworth . . . ©2021 G. Kim Blank (click to enlarge).

At least twelve key factors or moments (some of them conflated) can at this point be identified in chasing down and articulating what went into Keats’s rapid and remarkable poetic progress—or at least those that emerge from this study of Keats’s development:

~First: Keats’s constant practice in writing poetry since about 1814, and possibly a little earlier. This reduces to the result of such practice: the poetry that Keats writes. It involves (not surprisingly) Keats trying to get it right, which ties to his full clarity of purpose—to be a poet—that sounds everywhere in his drive to write enduring poetry. As a poet in search of a subject, his early work diddles with occasion, homage, and sociability, and there is little to move him forward. This factor of constant practice is necessarily connected to most of the others below. But at least one thread might be useful in gauging Keats’s progress, and it revolves around ideas of escape. First, for Keats, he voices a growing awareness that imagination for its own sake—as an escape, as it were, from the slings and arrows of the human condition—needs to evolve into imagination as a way of knowing and then representing the subject, and in a way that, paradoxically, does not escape from addressing those slings and arrows; Keats’s power, then, comes when he learns to how to poetically integrate imaginative powers and escape with human experience. Second, what develops is his deliberate escape from poeticisms of imagination only and from the confines of short history into the significance of long history, and this clearly works itself into the thematics of his greatest poetry. Then there is the complex issue of Keats’s developing style: Keat in his best work—that is, much of the last year or so of his writing, from about September 1818 (with his start on Hyperion) until September 1819 (with the completion of To Autumn)—develops syntactically natural styles that couple with a new semantic denseness; the new poetry is generally descriptive and expressive but with learned purpose, and without much distracting poetic decorum via odd or expected diction, intrusive rhythm, or over-determined sound for its own sake. Nothing is lost in the abstract, since, in that best work, he almost always keeps us within the experience of the senses. Keats, as he poetically matures, learns to balance—or negotiate—his natural inclination for passivity and sensual receptiveness with the non-passive desire for original creation; this becomes, as it were, his poetic position.

~Second, and corresponding with the above: Keats’s increasingly very deliberate study of poetry—most tellingly, of Shakespeare, Milton, Wordsworth, Chaucer, and Spenser—as well as art and drama (see his crucial analysis of Edmund Kean’s acting), beginning in earnest over 1815 into 1816, but set off by the early literary tutelage of Charles Cowden Clarke, the son of his headmaster at Clarke’s Academy in Enfield; it should be added that Keats’s progressive and free-thinking education at Clarke’s influences his direction, disposition, values, and tastes; and, very importantly, for its students, the school purposefully fostered the aptitude for self-mastering subjects, which is evident in the kind of scholarly discipline Keats takes into his desire to become a poet. Behind this is the obvious picture: Keats as a voracious, critical reader and re-reader; for Keats, reading is often the conflated act of discovery and own poetic coming-into-being—that is, for Keats, (re)reading is often paired with writing (many early depictions of Keats place him with reading material); as a result, it is not unprofitable to read Keats’s poetry as being about reading. Keats is also an underestimated student of poetic forms. For example, his parsing of the shortcomings of sonnet form takes us to his unique stanza forms in the so-called great odes of 1819. Keats’s annotations in what he reads (notes and underlinings) are material evidence of his vigorous critical bent. This deliberate study of poetry takes us to the third factor.

~Third: beginning 1816 and into 1817, Keats’s letters reflect the development of a

complex and increasingly original poetics that anticipates his progress; he

purposefully formulates what kind of poet he needs to become and what kind of poetry

he needs

to write. Recognizable, and by the end of 1817, and in particular his

letter of 21/27 December, is a direction in his thinking that we might usefully term

Keatsian.

From his poetics and then into his mature poetry, Keats becomes a poet of

controlled, contemplated risk, in both tone (in his lyrical poems) as well as in narrative

(in, for example, The Eve

of St Agnes and Isabella).

~Fourth: as part of Keats’s development of a poetics, is his understanding that knowing what kind of poetry he does not want to write is as important as figuring out what kind of poetry he desires to write. For example, consider Keats’s dawning by crucial recognition that no matter how extraordinary Milton’s accomplishment, and particularly that of Paradise Lost, Milton’s style is not his style; Keats comes to recognize this in his attempts with his Hyperion project(s). Keats nevertheless profits by, for example, understanding how Milton’s descriptions powerfully hold a subject, so that they act as both description and action; but Keats feel that Milton’s poetry actually draws too much attention to its style—and that is not what Keats hopes to exhibit in his poetry. Thus, as in the case of studying Wordsworth (as well as coming to terms with Hunt’s poetry and Robert Burn’s poetical career), Keats comes to distinguish his own poetical character in light of other major poets—his precursor figures. And in the case of Shakespeare, Keats learns that contrasts and oppositions are not exclusive, but deeply bonded by imaginative acts that embrace and then fold into the subject. Poetry cannot help but be artifice at some level, but, for Keats, the drive is to write poetry where artifice is fully subsumed by subject.

~Fifth: the crucial fact of Keats, starting mainly in late 1816, finding himself within an astonishing intellectual, literary, and supportive network. Much of this is initiated by and channeled through his meeting with critic, poet, publisher, and celebrity journalist Leigh Hunt through Charles Cowden Clarke in October 1816; more than a few within this grouping figure in the development of Keats’s poetics and in encouraging his poetic aspirations. This network includes Benjamin Robert Haydon (painter, public defender of art), John Hamilton Reynolds (poet, writer, reviewer, lawyer), Joseph Severn (painter), Horace Smith (poet, novelist), John Taylor (publisher, scholar), James Augustus Hessey (bookseller, publisher, journal editor), Benjamin Bailey (poet, scholar, translator), James Rice, Jr. (attorney), Charles Wentworth Dilke (scholar, civil servant), Charles Wells (solicitor, minor writer), Charles Brown (minor librettist, business person, but very supportive friend), William Haslam (business person), William Hazlitt (famous literary critic, essayist, lecturer), Richard Woodhouse, Jr. (scholar, literary advisor); and on the periphery, the brilliant young poet and implicit rival Percy Shelley, whom Keats also meets via Hunt. We can (for better and then worse) view Hunt as Keats’s early mentor and promoter, but moving away from Hunt’s sphere of influence (as a literary model, at least) is also key [and this can itself be a separate factor; see the Fifth Factor, below]. We cannot forget that Haydon also introduces Keats to the premier poet of the age, William Wordsworth, and they have contact in late 1817 into very early 1818—Keats is driven to articulate his deep ambivalence toward Wordsworth’s accomplishment and style. Within this above group, Hazlitt might be singled out as spurring and challenging Keats’s tastes and development: his ideas about poetic style and genius, as well as his critical lauding of the Elizabethan poetic temper, as well as his critical views about Milton, Shakespeare, and Wordsworth, push Keats to establish fairly particular poetic goals. Important, too, is Keats, in corresponding with Bailey, establishing his argument that the imagination is a prime agent of knowing and truth. [For a graphing of this, see Keats’s social network.

~Sixth: the Leigh Hunt factor: Without Hunt and Hunt’s connections, without Hunt’s early encouragements, and without Keats’s anxiety of influence concerning Hunt’s poetry and poetics, would Keats have continued on his poetic path as we know it—would he have developed that highly sought-after original voice? Almost certainly not. That is, at a certain point (emerging in 1817), and with a few close friends who advise him away from Hunt’s influence, Keats critically assesses Hunt’s poetic prowess and style in order to develop his own particular, unique direction. The limits of the poetry of sociability strikes him.

~Seventh: Keats short but valuable visit with Benjamin Bailey at Oxford over September into October 1817: by looking at Keats’s letters while with Bailey, and later to Bailey, we see that Bailey’s theological conceptualizing importantly challenges and begins to force Keats’s thinking about the imagination as a form of knowing, and beauty as a deep form of truth [see 3 September 1817 and 28 November 1817].

~Eighth: preparing Endymion for publication. By copying and reading over the poem as

it moves toward publication, Keats comes to an important moment of realization: it

is for the

most part the work of an immature poet, but he views the poem as a necessary step

in his

poetic growth; he declares, in effect, no more of that, and time to move forward.

That is,

Keats comes both to play down the poem and to place it in the larger course of his

progress,

agreeing that while it is slipshod,

its failure

is necessary as a step toward

being among the greatest

(letters, 9 Oct 1818).

~Ninth: on the immediate threshold of his greatest work, into his personal world comes

the agonizing death of his younger brother, Tom, in December 1818. The loss of

Tom profoundly deepens Keats’s thinking and feeling about mortality in the face of

death, suffering, sadness, and difficult resolve, and it shapes most of his thinking

about how

beauty, art, and nature will (to quote from his Ode on a Grecian Urn) remain, in

midst of other woe / Than ours, a friend to man.

This quality of depth and

profundity—and the understated style of expression—is simply not present in much of

his

earlier work. In short, the idea of death and duration, which must have been with

him since

the early deaths of his parents, is now to be more fully reckoned with in his thoughts

and

then into his poetry. We might say that this reckoning is the poetic struggle of full,

complex

consciousness.

~Tenth: not long after Tom passes away, Keats

begins what evolves into a very long journal letter to his remaining younger brother,

George, and his wife, Georgiana, who have moved to America in search of

opportunities. The letter, which dates from 14 February to 3 May 1819, and is taken

up on at

least thirteen days and amounts to almost 16,000 words (counting the transcribed poems),

works

through and up to the very threshold dates when he is writes his greatest poetry.

The letter

provides some of the background and, importantly, the momentum for the astonishing

leap his

poetry makes in spring 1819. The letter begins, mid-February, with Keats waiting for

spring to

rouse

his imaginative capabilities, and then it works its way through subjects,

theories, and concerns that are at the core of what separates his early poetry from

this later

work: life as an allegory, categories of indolence, mutability, disinterestedness

of mind, the

speculative mind, the meaning of Wordsworth’s

one human heart, speculations about human purpose, poetry being as fine as philosophy,

worries

about life as a poet, struggles with perfectibility in a world of death and loss,

the world as

a vale of soul-making, how pain and suffering are necessary for a feeling heart—and

at the end

of the letter, he mentions that he is working on a sonnet form more suited to natural

language, which in fact he puts into practice in the innovative stanza forms of his

odes. This

opportunity for conversation, set off by death and separation, is then a further step

toward

and factor in his poetic progress. So, the letter which, back in February, begins

by

confessing that his poetic life seems stuck, ends on 3 May with him writing, every thing is

in delightful forwardness.

~Eleventh: although as an adult Keats’s finances are in a constant state of uncertainty under the management of the family trustee, Richard Abbey, the trickle of funds he receives allows him to pursue his career as a poet—much to Abbey’s disfavor. That is, Keats does not have to work while he pursues his desire to be a poet. At the same time, Keats would have been aware that the clock was, as it were, ticking down on the period of time bought by his family money, and this, no doubt, is a source of urgency for his rapid poetic progress. The generosity of his closest friends also, at a few key moments, helps him.

~And finally, twelfth: this we might call the Junkets factor: Keats’s complicated, unique, and ultimately unknowable capacities—his innate creative and imaginative potential, his unlearned emotional and intellectual nature, his drive (will power) to succeed, and his profound ability to fuse novel relationship with inductive thinking that cannot be reduced to a moment, a cause, a reason, or even to a particular insight on the part of Keats. But without this unseen, insoluble Junkets factor, nothing else happens. As, for Keats’s greatness: It may be well that Keats is too much one of us by reminding us of what we forget: that the world is beautiful, mysterious, and sorrowful, and that the mind is capable of, at once, beholding these truths.

These, then, are some of the overlapping and moving parts of what propels Keats forward and underwrites his remarkable and remarkably fast poetic progress. They are not, of course, the whole story, but some features and factors that, in the course of the present examination, are seen to contribute to the growth of a poet’s mind.

The span and nature of Keats’s poetic progress might thus be distilled: Keats is a full-time poet for about four years, 1816-1819, with the first three years generally resulting in poor, random, or middling attempts to find a voice, a style, a worthy subject; this poetry is largely occasional, too often overly poeticized, and for the most part motivated by unformed yet serious ambition rather than informed purpose, with the subtext often reducible to his desire to be poet. Of course there are poetic moments that anticipate his unique form of greatness.

And in the case of Endymion (which takes up Keats’s attentions for the better part of 1817), the

project-poem openly acts as an apprenticeship to poetry, a test of perseverance, and,

in the

end, a self-warning about potential poetic pitfalls. Keats is fully aware that it

is a very

imperfect piece, despite the effort it took. It is a poem that also shows how Keats

was

certain that such a poem was going to be pulled into the moment of his own times—that

is, more

particularly, Keats was perfectly aware that the deeply partisan review culture of

his time

would, as it were, draw his attempt at an epic romance poem into the limiting,

small-mindedness of contemporary party politics; and in the end, after his death,

this

happens, and it immediately turns Keats into the victim he never wanted to be, beginning

with

an epitaph on his grave that he never wanted. His too-obviously

escapist poem could not escape. When poetry (or art) offends or challenges or complicates

culturally-determined tastes, or when it is simply not very strong, criticism can

degenerate

into value judgment clothed in politics and confined tastes. The easy criticisms can

level the

work with a range of labels: as treasonous, seditious, irreverent, diseased, flippant,

childish—these were all, in fact, put on to Keats’s poetry. His better work simply

transcends

those charges and qualities, and contemporary history is left far behind. And so in

determining the larger meaning of Keats’s poetry (beyond, that is, clamouring elements

that

tie him to his own material history), we should take him at his word, that his deepest

creative efforts are not directed to a passing public—to any thing in existence

—but, as

he writes, to the eternal Being, the Principle of Beauty,—and the Memory of great Men

(to Reynolds, 9 April 1818). This is the poetic

conversation Keats desires to have.

Keats’s last year of writing (mainly 1819) is marked by his success in finding and

developing

a voice and forms—and now highly conceptualized subjects—that balance yet conflate

intensity

and impersonality: there’s an empathetic imagination as a form of knowing that explores

the

mutual, mutable relationship of sensation and thought attuned to that larger principle

of

beauty. He now comes to achieve this without a forced poetic register, and with forms

that

frame the subject rather than detracting from it. Keats in part predicts this achievement

when, just on the verge of his great year, he declares his determination to write

independently & with judgment

(to Hessey, 8 Oct 1818). His emphasis means all.

Perhaps, then, we can conclude that Keats, in his final year of writing, arrives at moments of fine poetic judgement, and, thankfully, literary history has come to judge his work accordingly.