28 November 1817: Endymion’s Completion & the Truthful Imagination: Advancing Poetics via an Advanced Philosophy

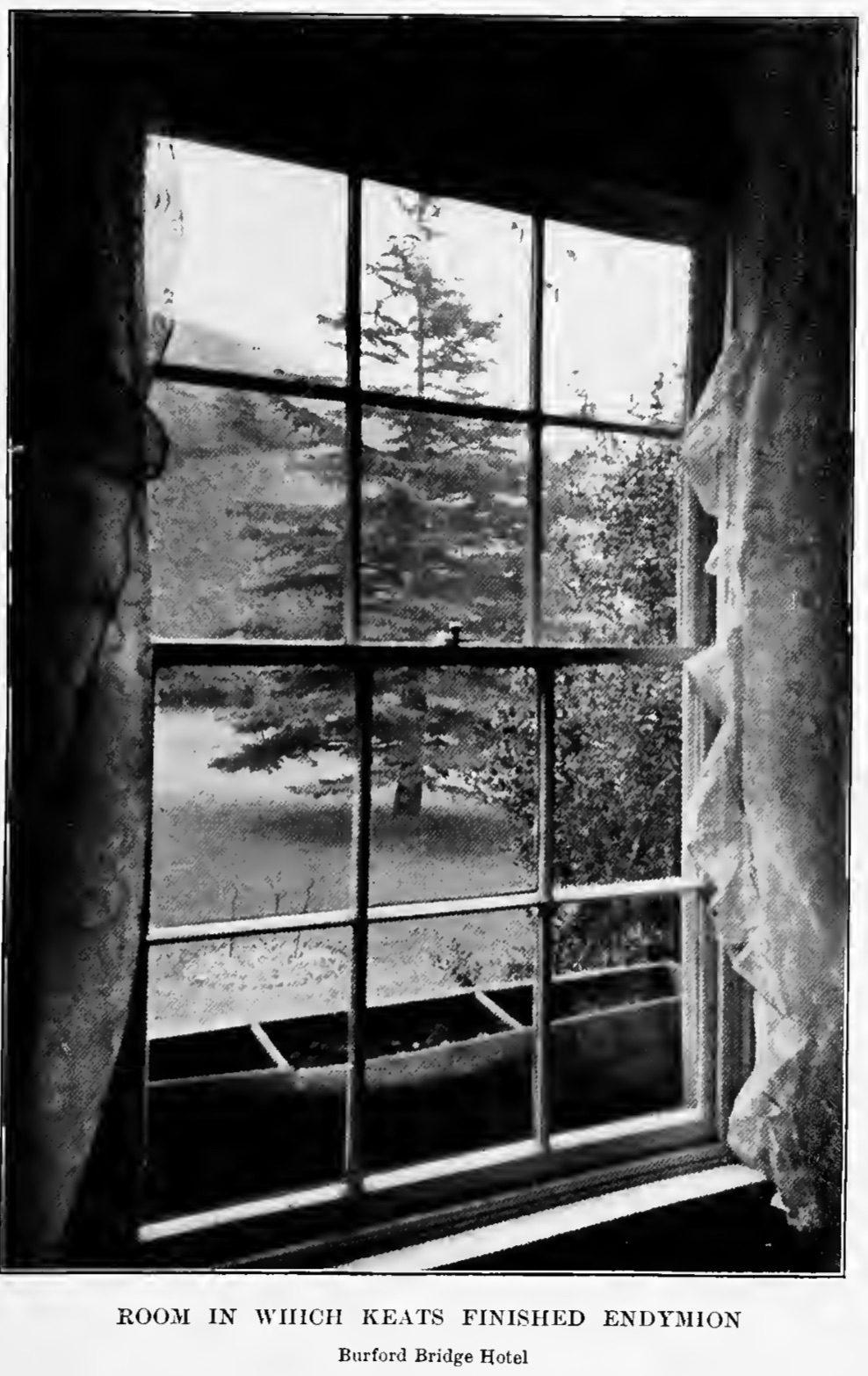

Dorking and Burford Bridge

The Fox and Hounds Inn, Burford Bridge, Surrey, two miles north of Dorking: Here,

at the

historic inn at the base of Box Hill (which Keats climbs), Keats completes a first

draft of

Endymion: he

writes Burford Bridge Nov 28. 1817

at the bottom of the completed draft. (The Fox and

Hounds is now the Mercure Box Hill Burford Bridge Hotel—offering, today, the finest British

cuisine the region has to offer.

Box Hill is also noteworthy for its plotful importance

in Jane Austen’s Emma, published 1816.) Keats has been at

Burford Bridge since 22 November, with a room that overlooks some gardens. He is back

in

Hampstead toward the end of the first week of December. Keats has just turned twenty-two.

It takes Keats about seven months to draft the 4,000 or so lines of what he calls

his

trial

poem, having begun Endymion toward the end of April 1817.

Between January and March 1818, he copies out the poem, revising and correcting as

he goes.

The poem is published the final week of April 1818 by Taylor & Hessey, who also publish

his final 1820 volume and assume rights to his first volume, Poems, by

John Keats. Writing Endymion is important; but, for

Keats, critically understanding its limitations and faults is far more important.

As a kind of

experiment, it fails, though for Keats it represents something to learn from and to

leave

behind; as a test of endurance, it passes.

While in Burford Bridge, and upon completing this first draft of Endymion, Keats writes a minor but interesting poem, in that, stylistically and thematically, it goes in two directions: one that points to better poetry, and one that harks back to more immature verse. The poem is In drear nighted December, and while it toys with repetitive rhymes (for example, feel it/heal it/steal it), with its fairly concise lyrical exploration of loss, forgetting, and feeling, and with its use of less strained tropes from the natural world, it anticipates more profitable composition than the too-often digressive Endymion.

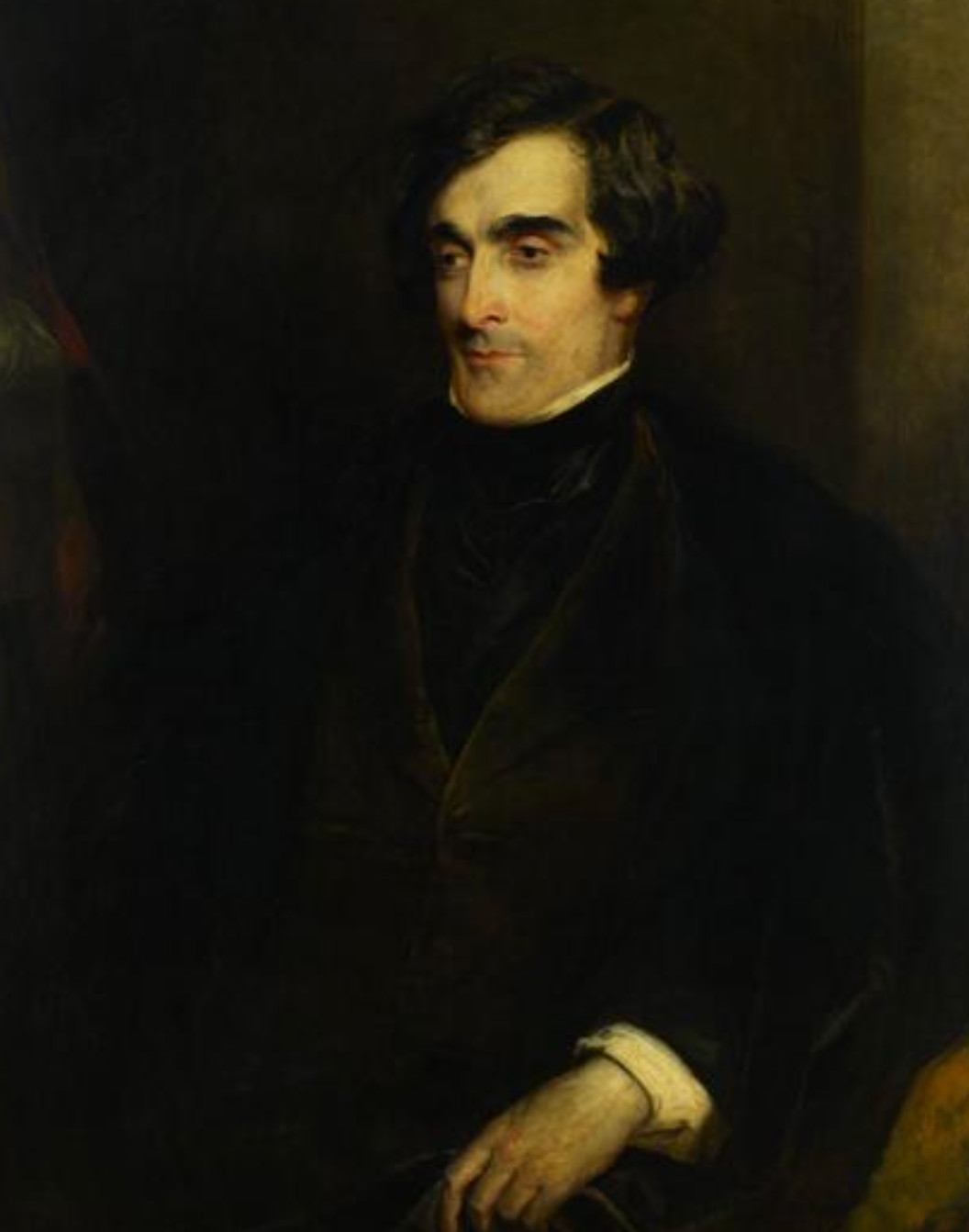

Z(John Gibson Lockhart), by R. S. Lauder, 1842

During this month, Keats will have seen that Leigh

Hunt, his friend and former mentor, as well as editor of the independent Examiner and someone with whom Keats has become strongly

affiliated, has been pummeled in Blackwood’s Edinburgh

Magazine—a flaming attack,

Keats calls it (letters, 3 Nov). Keats believes

that he, too, will soon be equally abused by Z,

the anonymous reviewer we now know to

be John Gibson Lockhart (in 1820 Lockhart

marries the eldest daughter of Sir Walter Scott,

thus suggesting the degree of Lockhart’s establishment connections). The attack on

Hunt is the

first we hear of the Cockney School of Poetry,

of which Hunt is proclaimed as its

overseer. Keats is right about condemnation by association, though it takes Lockhart

a while

to get to Keats: in the fourth installment of the eight attacks on the Cockney School

(the

August 1818 number), Keats’s character and poetry are at length described has being

thoroughly

infected by Hunt’s poetry, politics, and pretensions. At least on the poetry, Z is

generally

right: Keats in his early poetry has, indeed, often adopted the loose, nerveless

versification, and Cockney rhymes

of Hunt, something also noticed by friendly reviewers.

Keats will consciously shake off most the Huntian characteristics in the course of

his poetic

progress.

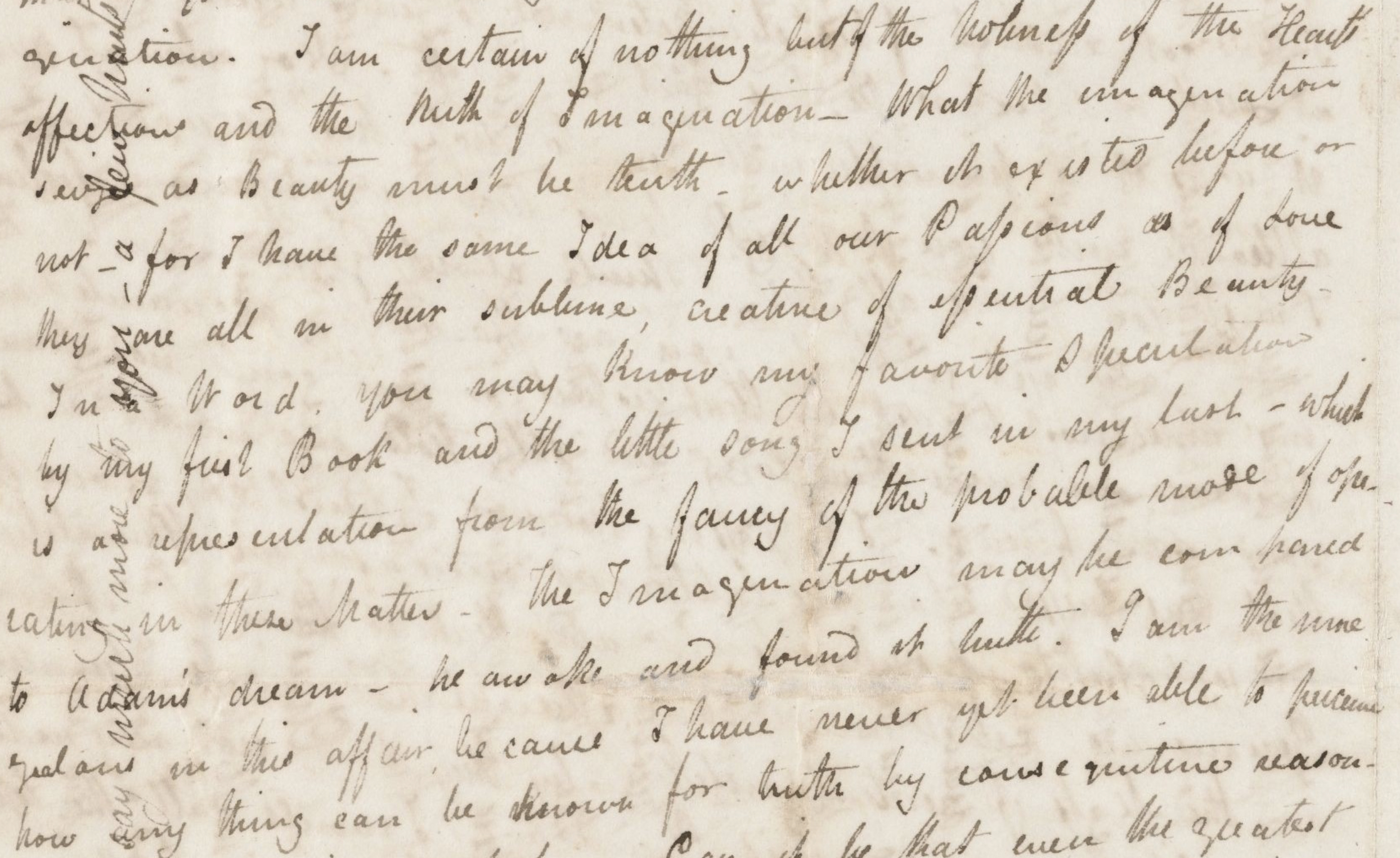

On 22 November, as Keats closes in on completion of that first draft of Endymion, he writes a terrific and terrifically important letter to

Benjamin Bailey, with whom he stays at Oxford

during September. The letter (which seems to react to and differ from Bailey’s ideas)

importantly anticipates some of Keats’s most important poetics—in particular, ideas

about the

camelion

poet, negative capability, the poetical character, the relation of beauty and

truth—which in turn anticipates the quality of the poetry that begins to evolve in just

about a year. With Bailey, who is a scholar well versed in both philosophy and literature,

Keats feels intellectually close enough to open himself up to speculate on the interrelated

subjects of genius, imagination, perception, sensation, thought, beauty, and truth.

He

attempts to understand the nature of his own character in the context of other men of

genius,

and he concludes that a determined character is impossible for such people; he

is, of course, thinking as much of himself as anyone else.

For Keats, the authenticity of the Imagination

is a way to truth, and in fact is its

own truth (and here he differs from Bailey): what is perceived and experienced can,

with

imaginative capabilities through sensations and empathy, come to be even more finely

conceived, recalled, and represented—and this is what Keats hopes he will be able

to capture

in his poetry. The imagination, Keats begins to see, operates very differently than

rationale

or consecutive thinking. Writes Keats, I have never yet been able to perceive how any thing

can be known for truth by consecutive reasoning—and yet it must be so.

To take part in

existence, it is not knowledge or reasoning that connects us, but rather the ability

to go out

of the self into what exists, and the imagination facilitates such an essential participation

into the life of things. O for a Life of Sensations rather than of Thoughts,

he pleads.

A complex mind

would be one both imaginative yet constrained, and able to exist

partly on sensation [and] partly on thought.

The end result would be the growth of

the philosophic mind,

which is no doubt an echo of William Wordsworth’s great proclamation of the restorative

strength that comes from accepting the meaning of human suffering and death (in Wordsworth’s

Immortality Ode). Here, then, we catch an early glimpse of Keats as philosopher: truth

operates deeply and with a deep, unresolvable paradox that knowing and not-knowing

can only be

held simultaneously by the operation of imaginative capabilities.

This letter of 22 November, then, signals Keats’s rapidly advancing poetics, which in turn advances his poetic progress. That is, the development of Keats’s poetics inevitably precedes his poetic development. The relationship of sensation and thought becomes particularly challenging for Keats to grasp, where the two not just coexist and intermingle but are necessarily indistinguishable as a condition—or maybe the condition—for great art and poetry. While sensation might solicit excess, thought might finely constrain that excess.

Keats now anticipates a time when Endymion will be behind him as he prepares to compose a very different kind of poetry propelled by very different motivations—and very different outcomes. As his preface to Endymion makes clear, he is very conscious of developing a mature, capable imagination.