1 December 1818: Death, Love, & Poetry: Tom’s Death, Miss Brawne’s Style, & Too Goutty for Verse

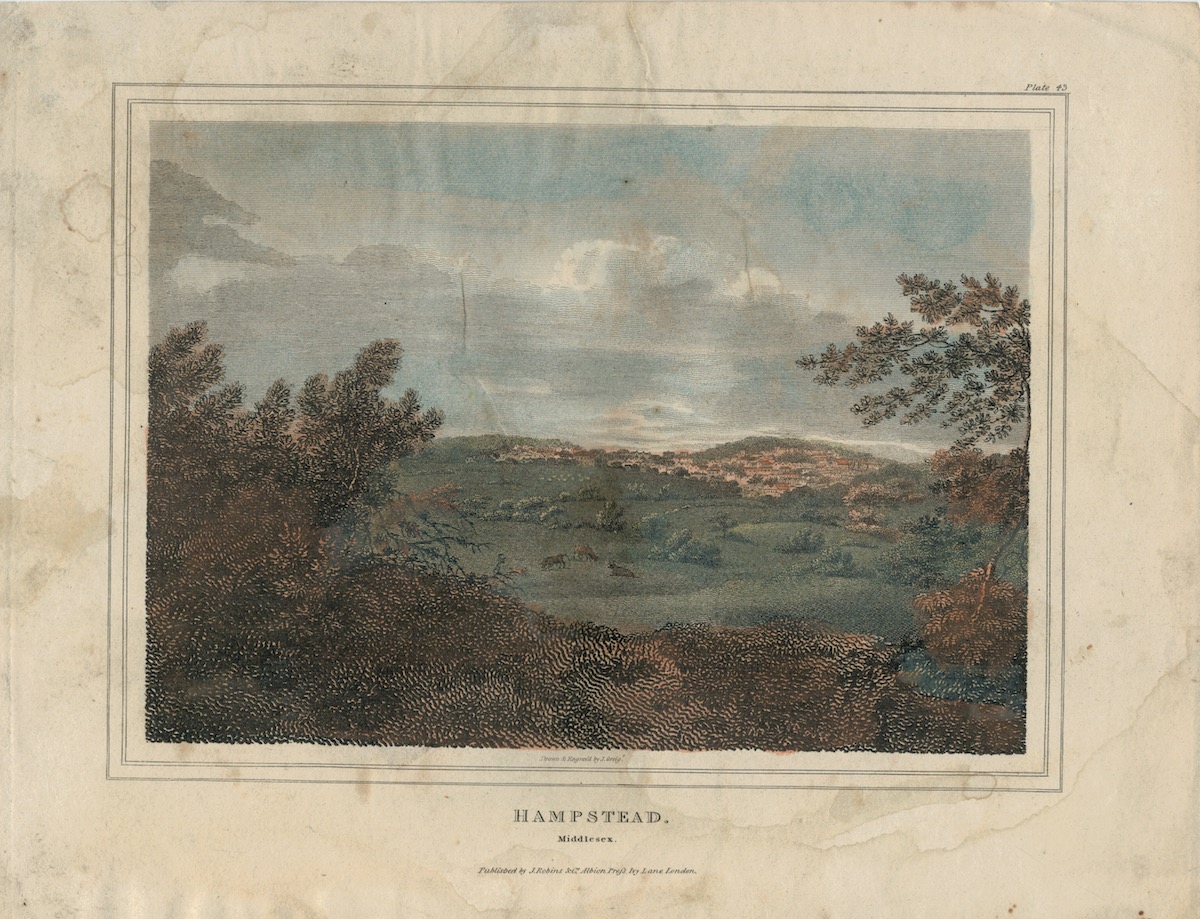

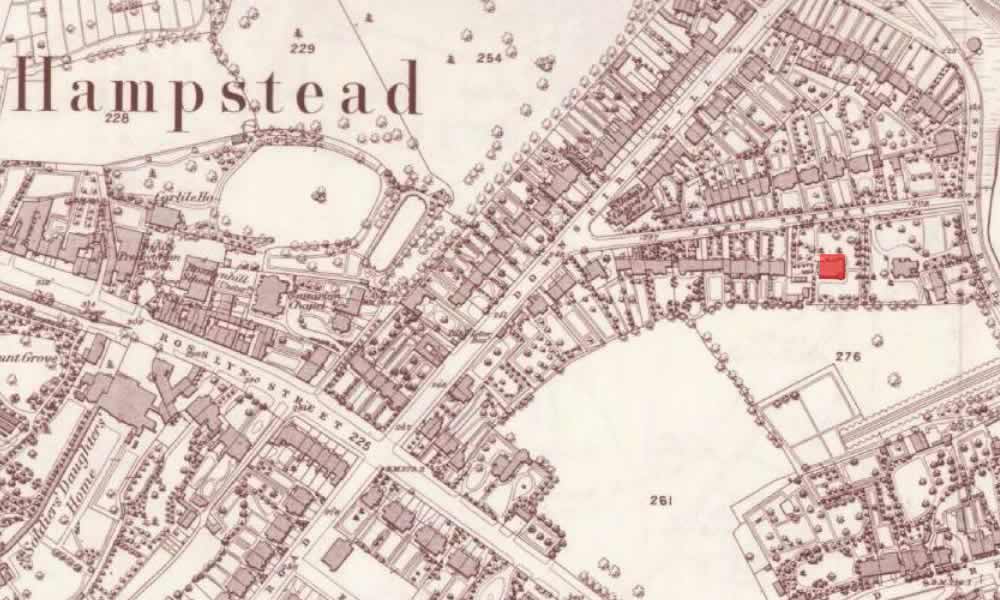

Wentworth Place, Hampstead

On the first day of December 1818, Keats’s younger brother, Tom, passes away. With the heartfelt invitation of his very good friend, the minor writer Charles Brown, Keats is almost immediately invited to room and board (for 5 pounds/month) at Wentworth Place, Hampstead (a double-house; Brown owns half). Tom had just turned nineteen. Tuberculosis also claims Keats’s mother, and it will eventually also track down Keats. Keats’s other younger brother, George, also dies of TB in 1841. It is not until much later in the 19th century that medical research establishes that TB is highly contagious. Tom is buried 7 December at St. Stephen’s on Coleman Street. [See 23 April 1804 for a note on the fate of the church and the Keats family graves.]

Keats will share half of one side of Wentworth Place with Brown. He has a small sitting room downstairs and an upstairs bedroom. The Dilke family (close friends with Keats) live in the other side of the house. Today, Wentworth Place is known as Keats House, a wonderful museum that celebrates Keats’s life and achievement.

George had earlier shouldered much of the care of

Tom’s long-lingering illness, but with

George having emigrated to America in June, much is now left to Keats, including maintaining

interest in the fate of his teenaged sister, Fanny, over whom he has a kind of tugging match with the family’s trustee/guardian,

Richard Abbey. All of Keats’s friends have been,

Keats records, exceedingly kind

to him in the aftermath of Tom’s death (letters, 16

Dec). They know of Keats’s deep love of Tom. Keats will also try to protect his little

sister

from the pain of Tom’s death, and in a letter to her written on the day of Tom’s death,

Keats

attempts to channel the extinguished hope onto himself: he ends his short letter to

Fanny,

Keep up your spirits for me, my dear Fanny—repose entirely in / Your affectionate

Brother

/ John.

This is remarkable—and touching—inasmuch as the letter is probably written after

Tom has passed; understandably, Keats very likely wants to tell her directly.

Consumption imposes a kind of drawn-out, agonizing inevitability on its victims. Keats

admits

that in the final phase of Tom’s slow decline

(beginning in the middle of August), he could not work very much. Keats will later

this month

write that the last days of poor Tom were of the most distressing nature

(to the George

Keatses, 16 Dec). Getting started on sustained composition is difficult; his Miltonic

Hyperion is stalled—it will (in two unfinished incarnations) become

permanently stalled. He writes, my pen seems to have grown too goutty for verse

(16

Dec).

Sometime between mid-August and December 1818, Keats meets the intriguing Fanny Brawne (the best bet might be mid-November), in whom he

begins to take some coy yet serious interest. Keats describes Fanny to his brother

George and sister-in-law Georgiana in a long letter (16 Dec 1818-4 Jan 1819): he finds her

beautiful and elegant, graceful, silly, fashionable and strange,

and he goes to some

length to describe her hair, fine nostrils, mouth, shape, profile, arms, and feet—and

her

manner. At this point, the Brawne family (the fairly well-to-do widow Frances and

her three

children, with Fanny, 18, being the eldest) live not far from Wentworth Place.

Although Keats is attracted to the stylish Fanny, during this fall he has some lingering interests in an older woman of

apparently independent means, Isabella Jones.

Keats had an amorous sea-side adventure with her dating back to

May 1817, but he has reconnected with Isabella by chance. And for at least one period

of this

fall, he remains distantly haunted by a certain striking and flirtatious Jane Cox (Charmian

); he confesses to a sleepless night

thinking about her (14 Oct). Through the next two months, Keats has lingering throat

problems

(perhaps set off while on the Island of Mull in July 1818), which may be related to

early

signs of consumption. Keats at this point has become impatient with and irritated

by Leigh Hunt’s literary tastes and aspirations. Almost as

a response to go beyond Hunt’s poetry and poetics, he cites William Hazlitt’s comments (on William Godwin’s genius) to suggest a possible direction: intense

study of the human heart and engaging the value of a capable, ranging imagination.

Keats’s emergence as a great poet naturally involves his struggle with being a modern poet. More important, however, are his very deliberate aims to represent and embrace larger, transhistorical topics that address the ages—joy and sorrow, death and immortality, nature and art, certainty and mystery, truth and beauty, dream and reality, imagination and consciousness, thought and feeling, sensation and knowledge. This can be said in a slightly different way: While Keats is of course tied to history (who isn’t?), and he can be subject to what might be called hyper-contextualization (again, who can’t?), it is clear that Keats’s progress is determined by his hope to write poetry that not only transcends history but functions to deny history’s hold over the quality and direction of his work—and the subjects on which he works. Keats’s desire, then, is for independence, controlled intensity, and poetic endurance—not for passing relevance and transient, occasional topics. He does not want to be pegged as a merely suburban poet with suburban tastes, though in much of his early poetry he in fact is such a poet. Keats will also evolve forms—in particular, a shorter odal form that complicates the idea of praise and address—that do not compromise his tone and expression. Discovering this form (and its slight variations) through study and an acute poetic sense, as well as by a critical parsing of established sonnet forms, is absolutely key for his progress. Keats comes to be aware that, for him, a lyric voice has more lasting qualities that allow him to represent his own, more natural voice—a voice that does not ventriloquize others, or that is designed for temporary entertainment or short-lived interests.

So yes, we can of course squarely place Keats in history, within a literary movement, and within a certain Regency London milieu. But Keats’s letters and greatest poetry make it utterly clear that the drive behind and the meaning in his poetry is to challenge the single-mindedness and limited certainty of historicization. Great art has no time. What is it in art, in the truth of beauty, that teases us out of our own moment and into all moments? What is it that connects us to nature and to human nature? What are the desires and qualities of human nature? What does the imagination allow us to see, feel, and express—is it a genuine form of knowing? Look upon a silent urn, listen to the song of a fading nightingale, perfect the experience and representation of a stilled yet moving season . . . . The principle of beauty and complex capabilities of the imagination move Keats forward—not the sentimentalized leisures of composition or the need to give direct, restrictive expression of his own time and place. Again, Keats conceptualizes his idea of great art as engaging with and existing within larger worlds than his own brief moment— in worlds of human pain and artistic beauty, worlds of a larger, unknowable intelligence, within which the mind attempts to grasp experience. (Keats perhaps best grapples with expressing this in his journal letter of 21 April 1819 to the George Keatses, just, in fact, as he composes his greatest work.)

We might think back to the moment, in early March 1817, when Keats first looks upon

the Elgin

Marbles. Keats is struck by the silent yet eternal power of their beauties. Keats

knows little

about the era from which they emerge; he knows little of what exactly these figures

represent;

he knows nothing of their creator or creators, who commissioned the work, where they

originally stood, from what materials they are made. This, for Keats, matters little.

What,

then, do they possess that sees them through and beyond their own time and into all

time—and,

intriguingly, how do they work themselves into and become part of his imagination?

Those

solicited feelings of grandeur

and magnitude

weigh heavily upon our own

mortality, and the feeling is undescribable

(On Seeing the Elgin Marbles).

Keats will hope to lift his own poetry to solicit similar feelings, to that moment of sublime, to profound uncertainty and, paradoxically, truth. The story of truth beyond facts, of what lifts us beyond mortality, thus becomes part of Keats’s poetic progress.