21 December 1817: Keats as Kean, Kean as Keats, Endymion as Filler

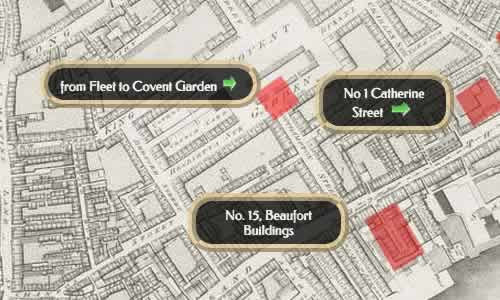

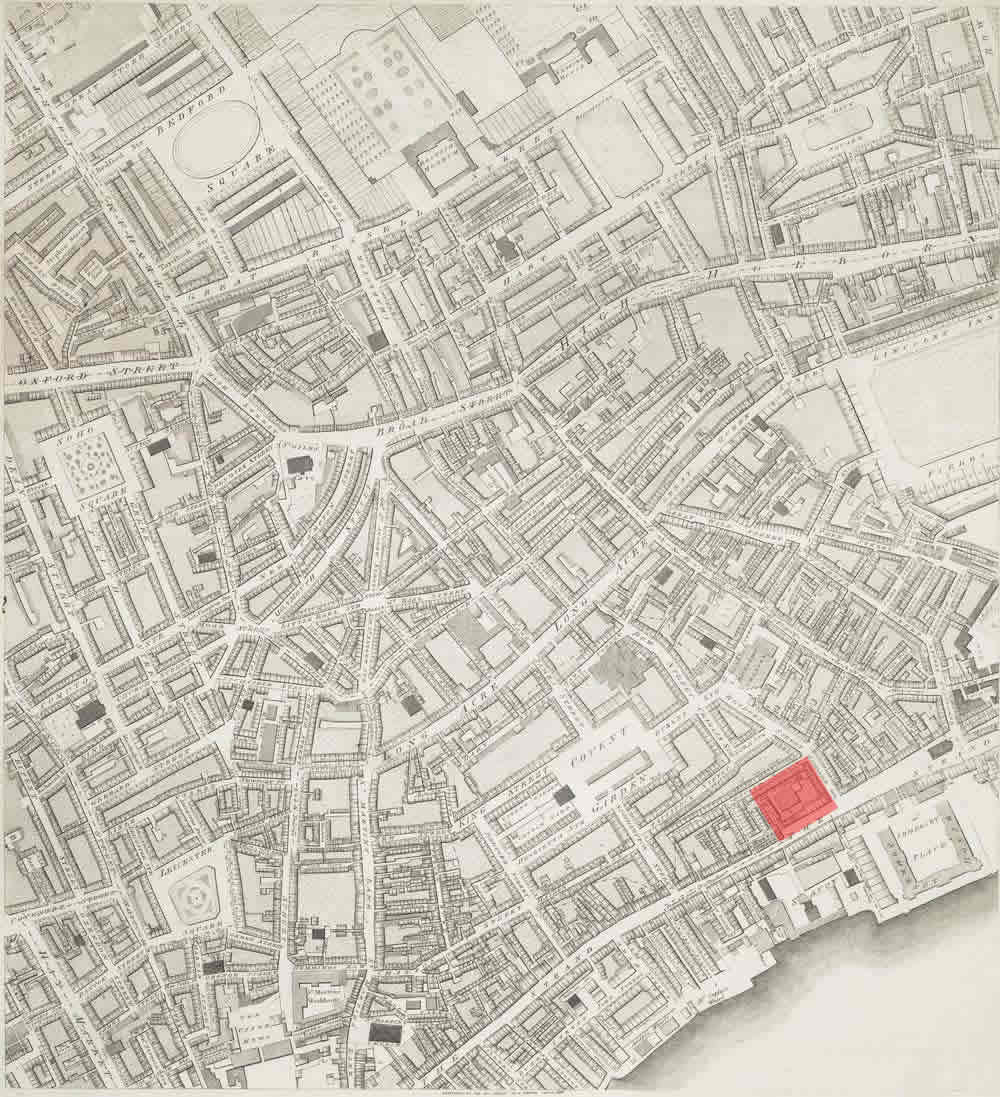

Offices of The Champion. On this day, Keats, subbing in for his good friend John Hamilton Reynolds, publishes a theatrical review for The Champion on the legendary actor Edmund Kean in the title role of Richard III, though Keats draws on Kean’s other performances and roles.

John Scott is editor of The Champion (first published in January 1814), which is known

as a liberal-progressive reviewing paper. Scott goes on to become the editor of London Magazine in 1820. In February 1821 (the same month Keats

dies), Scott is killed in a duel that evolves hostilities between himself and writers

for

Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, and in particular, John Gibson Lockhart, who earlier publicly (though

anonymously) ridicules and condemns Leigh Hunt and

the Cockney School,

and then, also, Keats and his poetry. (See 16 February 1821 for

more on the duel’s context.)

Keats’s connection with the magazine mainly comes via Reynolds, who writes criticism and poetry for the paper. Reynolds writes a positive review of Keats’s 1817 Poems for the magazine. The magazine also publishes some of Keats’s poetry, including On the Sea (17 August 1817) and, more importantly, On Seeing the Elgin Marbles and To Haydon with a Sonnet Written on Seeing the Elgin Marbles (9 March 1817); the Elgin marble poems are published in The Examiner on the same day.

Coming to terms with Kean’s acting style is highly

significant for Keats. Keats describes Kean as uncannily focusing on voice, language,

and

elocution—on the syllable, even. The drama, in short, resides with the intensity Kean

puts

into the words; they are, in effect, the objects of his acting, Keats posits. In praising

Kean, Keats in his review turns to what he believes great poetry possesses: A melodious

passage in poetry is full of pleasures both sensual and spiritual. The spiritual is

felt

when the very letters and points of charactered language show like the hieroglyphics

of

beauty:—the mysterious signs of immortal Freemasonry!

The giveaway in this enthusiastic

and critically probing statement of course points to what Keats is attempting to fashion

through his own developing poetical character: a voice that will bear both the sensual

and the

spiritual in creating lasting beauty via physical language itself—the measured efficacy

of

those words on the page—without being overbearing or acting in excess. Again, Keats

projects

on to Kean’s dramatic style what he desires of and in his own poetry, since Kean,

according to

Keats, becomes the lines themselves—he is, at it were, the chameleon actor: Kean,

Keats

writes, has this intense power of atomizing the passion of every syllable—of taking to

himself the wings of verse.

Keats holds that Kean becomes

the thing he describes;

Kean delivers himself up to the instant feeling.

Kean becomes the subject that he

articulates. This anticipates what Keats strikingly sounds toward the end of 1818,

when he

writes that the poetical Character

is chameleon-like, in that it assumes whatever

Body

or state it takes as its subject (letters, 27 Oct. 1818).

Despite, then, having some evolving sense of the direction his poetry must take, it

will take

Keats about a year to consistently step away from poetry that either seems random

and for its

own sake, or that, at worst, wallows in unnatural poetic affectations. Endymion, the 4,050-line poem that takes up a great deal of 1817 (and represents

more or less the middle phase of Keats’s poetic development) is in fact a good example

of a

poem that, at too many moments, is overloaded with diffuse description, poetic posturing,

and

sensuality without sense or spirituality; moreover, its form—couplets—are too often

driven by

diversionary rhyme, despite being somewhat experimental. The poem seems in search

of a

subject, and does not (like Kean) with gusto embody the subject that it can turn and

explore.

When Keats writes that a significant part of his purpose in writing Endymion is to see if he can make 4000

lines of one bare circumstance and fill them with Poetry

(letters, 8 Oct 1817), we are

entitled to say that the poem is not much more than filler. Toward the end of drafting

the

poem, Keats is greatly aware of its deficiencies; such awareness is a good thing.

Keats writes reviews for The Champion in December 1817/January 1818.