3 February 1818: Another Hazlitt Talk, No More of Wordsworth or Hunt,

& Composting

a Head in a Garden-Pot

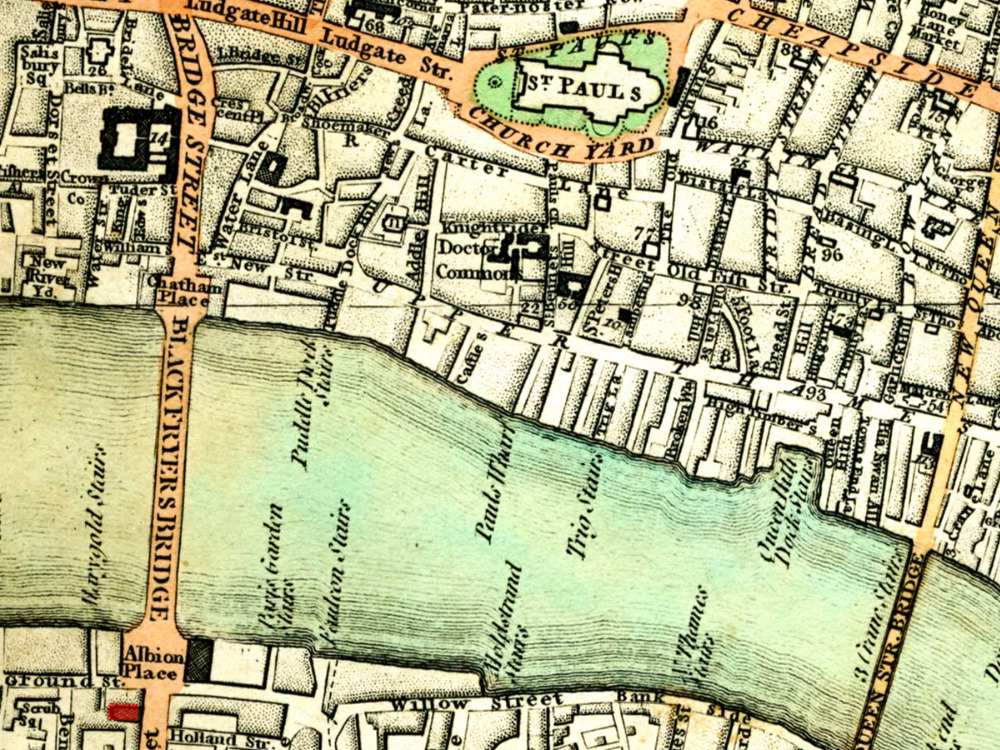

Surrey Institution, Blackfriars Road, London

On 3 February, Keats attends another of William Hazlitt’s successful lectures on the English poets at the Surrey Institution (mainly on Pope and Dryden). The lectures began 3 January, running until 3 March. Although his passions reside in philosophy and in painting (which he tries in his early years), Hazlitt’s fame (yet modest financial success) by 1818 resides mainly in his work as an essayist, journalist, literary critic, and lecturer. He knows many of the great figures of the age, including Wordsworth, Coleridge, Leigh Hunt, Charles Lamb, and Robert Southey, and he will have plenty to say about them, particularly in his Spirit of The Age, published 1825. Hazlitt’s natural and energetic prose style, coupled with his desire to speak out and have the final say, didn’t always function to create friends.

That Keats, aged 22, knows and converses with someone like Hazlitt tells us about the circles Keats now moves easily within—a faction of liberal London intelligentsia of the day—though he is nowhere near as famous or experienced as most of his literary/artistic friends; that Keats is extremely attentive to Hazlitt’s critical views tells us something about the direction of Keats’s poetic progress. [For more on Hazlitt’s influence on Keats, see 22 October 1818.]

Hazlitt is the third in what might be called the Triple-H influence on Keats’s poetics, the others being his friends Hunt and Haydon. But Keats has now largely moved away from Hunt’s poetical sway (mainly the poetry of fancy and sociability), especially now that he is close to leaving his year-long project of Endymion behind. Haydon (who casts aspersion on Hunt’s influence) continues to encourage Keats’s independence, ideas, and genius in conversation and letters; and Hazlitt’s thinking about Wordsworth’s poetic egoism and the qualities of truly enduring poetry—like that of Spenser, Chaucer, Milton, Shakespeare, and the Elizabethan poets in general—are developed by Keats in what might be called his epistolary poetics: letters to his friends.

Keats writes a letter to his friend John Hamilton

Reynolds, 3 February, about the bullying, limiting egoism of contemporary poetry, and

he mainly has Wordsworth in mind: We hate

poetry that has a palpable design upon us [ . . . ] Poetry should be great &

unobtrusive, a thing which enters into one’s soul, and does not startle it or amaze

it with

itself but with its subject. [ . . . ] Modern poets differ from the Elizabethans in

this.

Each of the moderns like an Elector of Hanover governs his petty state, & knows how

many

straws are swept daily from the Causeways in all his dominions & has a continual itching

that all the Housewives should have their coppers well scoured: the antients were

Emperors

of vast Provinces, they had only heard of the remote ones and scarcely cared to visit

them.—I will cut all this—I will have no more of Wordsworth or Hunt in particular

[ . . . ]

Why should we kick against the Pricks, when we can walk on Roses? Why should we be

owls,

when we can be Eagles?

Poetry, Keats suggests, needs to avoid pettiness, pedantry, and

personality. Why remain flightless in the dark rather than soar above and see all?

Once more, Keats’s strong and significant declaration of independence—I will cut all

this

—derives a fair amount from Hazlitt,

who is consistently critical of Wordsworth’s

all-consuming subjectivity, while applauding the Elizabethans. Keats desires a subtle

yet

intense poetic voice—great & unobtrusive

—and one that comes from the subject rather

than from trifling, picky subjectivity and egotism. Keats desires to take in a larger

scope, a

scope without an obtrusive and petty palpable design.

The subject, and not

subjectivity, must govern poetry.

Keats will not want his poetry to be, as it were, driven by circumscribed, trivial

purpose.

At this point we hear Keats more determined than ever to, as it were, distance himself

from

his contemporaries, those Modern poets.

But we have to remember: Keats hugely respects

Wordsworth’s depths—his moments of grandeur

and genius, in fact—in understanding nature and the complex relationship between joy

and

suffering, based on restoration and acceptance. In all of this then, here is one of

the

moments we see Keats strongly articulating his personal aspirations, even with a little

rhetorical panache.

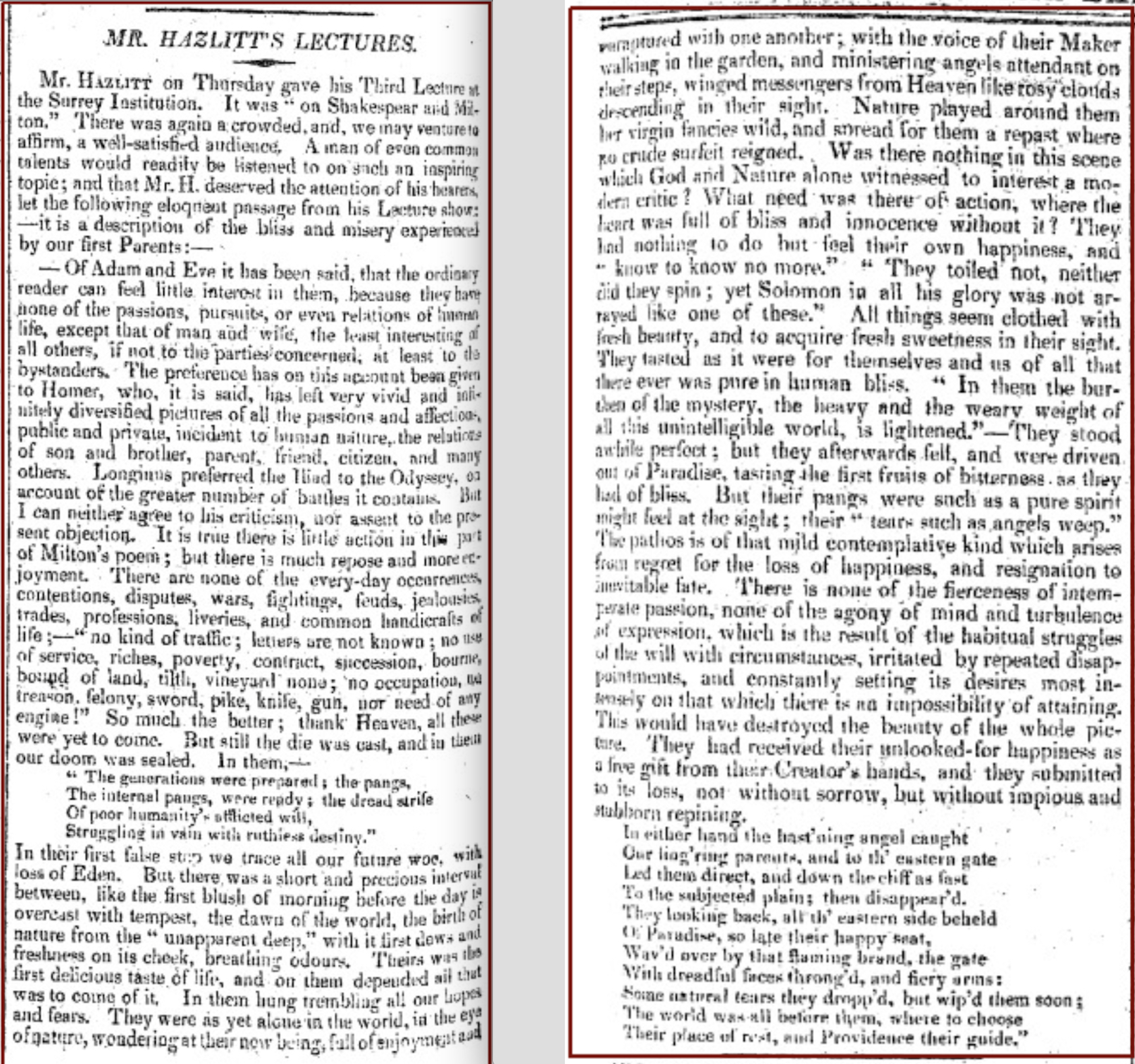

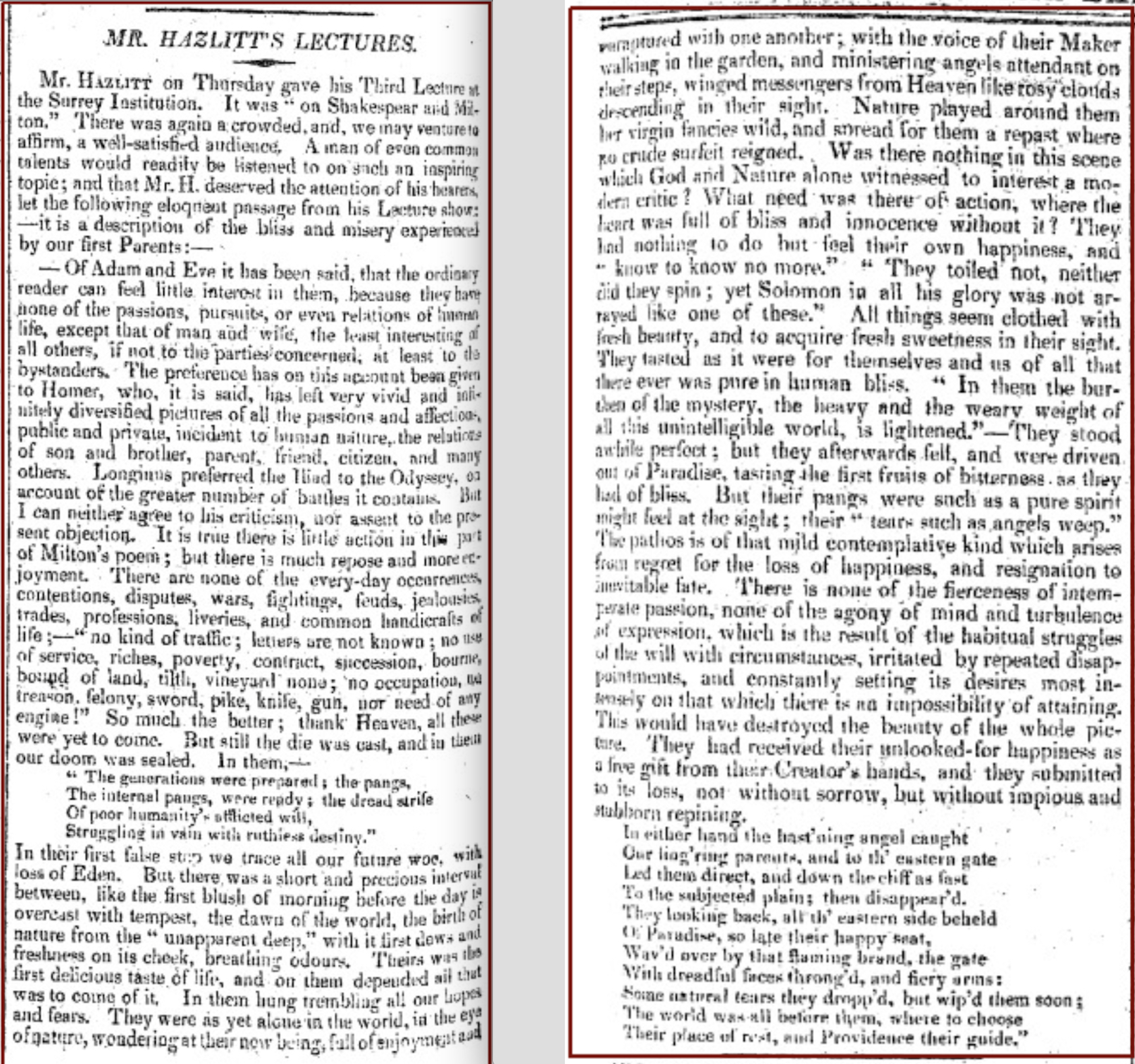

The fourth lecture by Hazlitt on 3 February further impacts Keats. It motivates him

to turn

to a work named in the talk: Giovanni Boccaccio’s 14th-century collection of 100 stories,

The Decameron. In particular, over the next few months, Keats significantly

massages one of its tragic tales, one of greed, illicit love, and murder, with an

added dab of

the supernatural to assist with the plot: Isabella; or The Pot of

Basil. In Keats’s hand, the story of socially—or economically—mismatched lovers

generally lacks much that is profitably suggestive or even compelling, despite a few

digressions on melancholy and love, as well as some sideways commentary on the false

pride of

avarice. It generally pleases with art rather than by probing with thought; that is,

at

moments, the poem seems arbitrarily decorative rather than purposefully dense or complex.

For

example, the poem might spend a little too much time describing how the tender feelings

of the

secret lovers—Lorenzo and Isabella—grows irresistibly passionate with, on the way,

faster-beating hearts, fevered restraint, pale foreheads, much anguish, some flushing,

much

unbearable desire, timid lips growing bold, the sharing of the lovers’ fragrance,

not to

mention comparisons with unfolding blossoms that need some tasting, as well as great,

blissful

happiness growing like a lusty flower in June’s caress

(72). Whew! Teasing narrative?

This is sensual excess, but is it senseless excess?

Isabella and the Pot of Basilby William Holman Hunt, 1868 (formerly part of the Delaware Art Museum; auctioned to a private collector, 2014). Click to enlarge.

Well, despite this excess of one kind or another, the poem remains fairly assured

in its

formal qualities and general narrative fashioning. Keats, though, ends up thinking

that Isabella; or The Pot

of Basil is simple, weak, and mawkish (amusing or diverting at best), and

therefore open to criticism and dismissal. With its gothically-inflected plot line,

it brushes

up against sensationalism that, Keats knows, could sink it into the farcical. Nevertheless,

there remains some novelty and something potentially evocative in Keats’s (re)telling:

yes, we

can often read about the doomed loved of young, pining, passion-filled lovers from

different

worlds. But now, piggybacking on Boccaccio, we have the brutal murder of one lover,

Lorenzo,

by profit-driven brothers of the other lover, Isabella; their intention has been to

marry her

off her to some propertied nobleman, and so they must eliminate Lorenzo, a poor lad

from the

lower classes. The brothers use their swords to kill him; they bury Lorenzo’s body

in a

forest; and off they ride, Each richer by his being a murderer

(224). Eventually a

spirit comes to Isabella and tells her the truth of Lorenzo’s fate; she exhumes and

decapitates the body; and, after much grooming of and swooning over the head, she

secretly

places it in a garden-pot, adds a little soil, and plants some basil; where, composted

by the

head and watered by tears of love and loss, the plant fairly flourishes while Isabella,

withering, obsesses over it. When the head-filled pot is taken by her suspicious brothers

who

discover the rotting but recognizable head, she quite naturally pines away and dies

forlorn;

the brothers flee.

Keats is not quite finished with the bones of this story. In two later poems written in the first months of 1819, he will return to medieval romance and once more to stories of struggling love and unsettled, mismatched lovers—but now he does so in both extraordinarily condensed and expansive forms, and, better yet, with measured intensity that identifies these later poems as Keatsian: La Belle Dame sans Merci and The Eve of St Agnes.

In these later poems, then, we see how the treatment of a subject over a period of

not much

more than a year marks a clear measure of Keats’s poetic progress. And now think how

far he

has come since his randomly-plotted, stretched, and overly poeticized poem about other

mismatched lovers, drawn from classical myth, Endymion, written mainly in 1817. We

can at the very least conclude that Keats is attracted to the poetic circumstance

mismatched

lovers, since he again returns to it in Lamia, written mainly July-August, 1819, and now we have mismatched lovers in

the form of a mortal human (a novice philosopher, no less) and supernatural woman-serpent.

Notably, Keats writes this later poem for potential financial success, thinking it

has

something sensational about it that the public might take to. At the same time, he

places it

above Isabella, calling his earlier poem weak-sided

(letters, 22 Sept. 1819),

while the later poem is written with deliberate Judgement

(letters, 11 July 1819). In a

way, the performance of Lamia seems more purposely professional than almost all of his earlier work—yet,

in its sensually-clothed topic shifts and convoluted messing around with truth/illusion

issues, the irresolute handling of the story leaves us with an uncertain blend of

naughtiness

and knottiness.