5 February 1818: Busy Times, Busy Thoughts

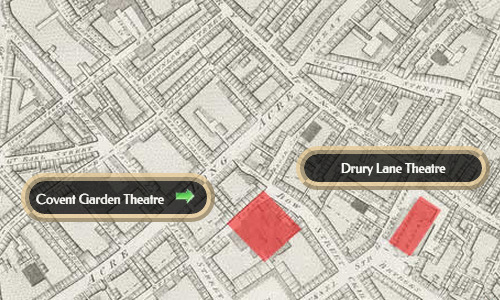

Covent Garden (theatre), London

Keats watches H. H. Milman’s Fazio

(first staged as The Italian Wife in December 1816) at Covent

Garden—a tragedy mainly about the fall of Italy, with some guilt and jealousy thrown

over the

subject. Keats writes that the play hung rather heavily on me

(14 Feb).

Once more, and much like the month before, this is a busy time for Keats: besides

working

hard to prepare his long poem Endymion for publication, the day

before he is at Leigh Hunt’s with the free-thinking

young poet Percy Shelley, writing sonnets on the

Nile as friendly competition;* the night before that he attends one of William Hazlitt’s influential lectures on English poetry (the

fourth in the series; he attends two more on the 10th, and 17th); on the 11th he once

more

dines at Hunt’s, with Shelley and his wife, Mary

(to-be novelist, author of Frankenstein) present, as well as

Thomas Love Peacock (poet, critic, and

novelist), Claire (Jane) Clairmont (daughter

of William Godwin’s second wife, stepsister to

Mary Shelley, pregnant by Lord Byron), and Thomas Jefferson Hogg (minor novelist). This is quite a

lineup for the young Keats on just one casual night. In a way, the evening of the

11th even

rivals the immortal dinner

of 28 December 1817, so-called by Keats’s friend, the

historical painter Benjamin Robert Haydon, after

he gathers Keats, William Wordsworth, Charles Lamb, and a few others to view his large canvas

which includes some of them.

Sometimes the popular imagination constructs Keats (and the Romantic poet in general)

as a

self-secluded, lonely, embowered figure. Keats is anything but, and neither are most

of his

canonical peers: they generally become great writers by reading, studying, writing

about, and,

crucially, meeting with other writers and thinkers. It turns out an intellectual network

is

more important than living the life of a solipsistic, solitary, wandering, leaf-loving

figure,

though the Romantic poet nonetheless often portrays this posture. Byron wonderfully mocks this Romantic stereotype in Canto 1, stanzas

90-91, of Don Juan, where poets, like Wordsworth, thinking unutterable things,

wander by

brooks and, with a mighty heart,

throw themselves within the leafy nooks

in

order to commune with their high soul

; the result is unintelligible

poetry.

Tomorrow, the 6th, Keats sends Book II of Endymion to his publishers. Book I is delivered 20 January, though he adds what he feels are crucial lines about a week later (Book I, lines 777-81), which introduce the pleasure thermometer passage (see letter, 30 January). By the end of the month, Keats does some of the proofs for Endymion, which is officially published toward the end of March. He will be greatly relieved to have his large, traipsing poem behind him in order to pursue other, quite different directions.

But at this time in his thinking about poetry, Keats finds himself turning away from

how

vanity, egotism, and pedantry have crept into contemporary poetry. For Keats, this

marks some

kind of exploration of how a capable imagination can patiently open itself to both

sorrow and

joy. Thus on 19 February he writes, let us open our leaves like a flower and be passive and

receptive.

This fits into his larger theory of how the true poetic character (itself

beautiful, like a flower) embraces its subjects without fractious reasoning or reaching.

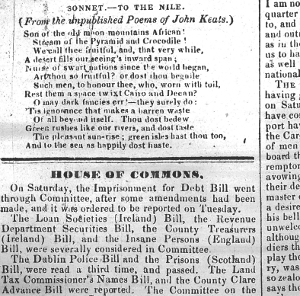

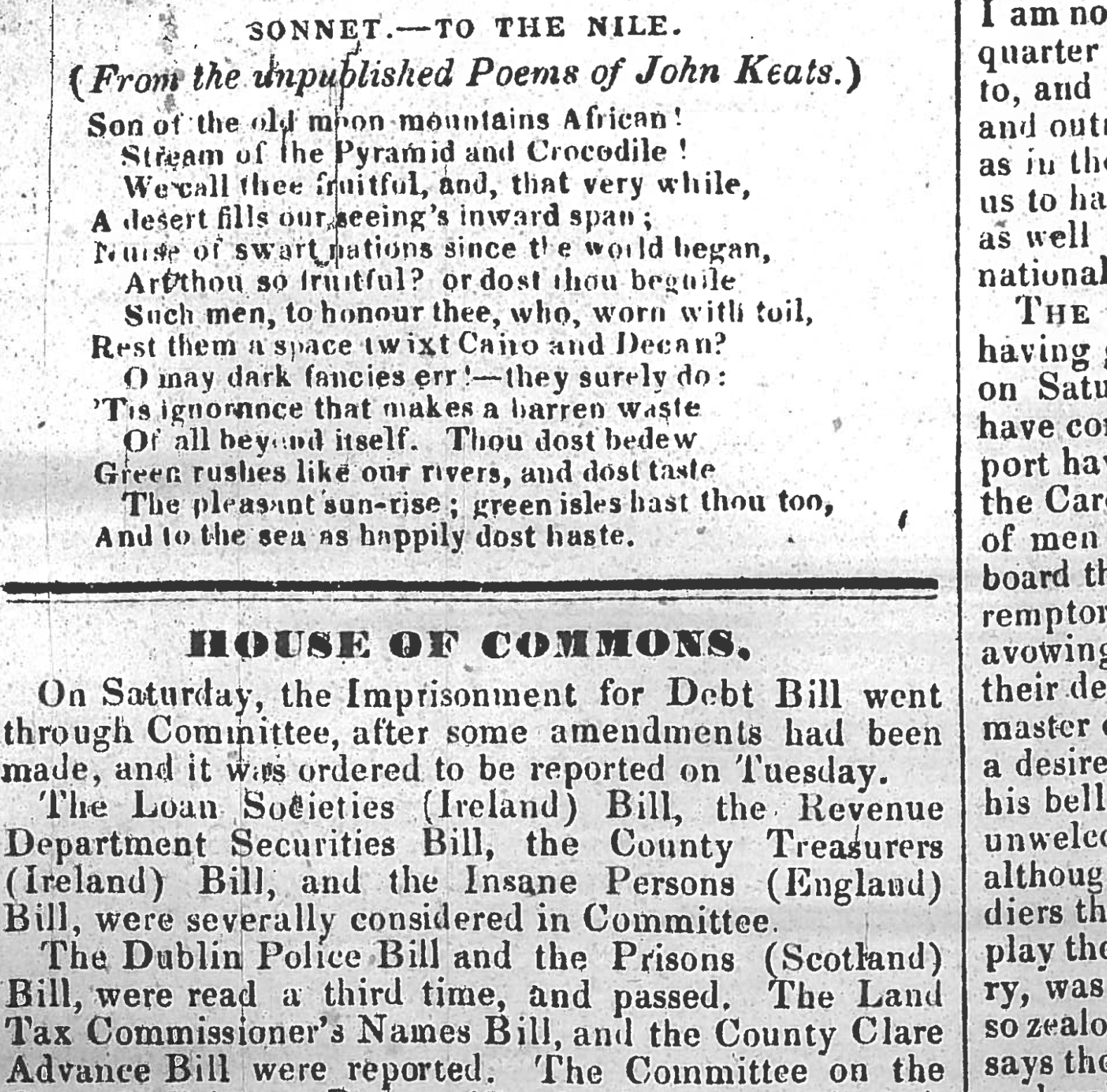

*Keats’s contribution to the fifteen-minute sonnet-writing competition on 4 February

is To the Nile. It remained

unpublished until 1838. Shelley and Keats were apparently finished within the time

limit,

while Hunt remained working on his into (as they say) the wee hours. Keats’s sonnet

is pretty

bad, which is to expected: taking a vaguely allegorical tact, it addresses the Nile

as

Chief of […] the Crocodile,

and goes on to say that the river dost bedew / Green

rushes.

Shelley’s resulting sonnet is equally indifferent, and plays with the idea the

Nile as both good and bad. Hunt’s effort is a little better—but that may have been

because he

actually tried.