20 February 1818: Pall Mall Pictures & Delicious, Diligent Indolence

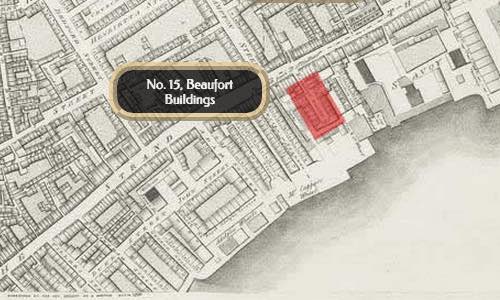

British Gallery, No. 52 Pall Mall, London

On this day, or slightly before, Keats sees an exhibition at the British Gallery (also known as the Pall Mall Pictures Galleries or British Institution, and formerly the Shakespeare Gallery). He views a few indifferent contemporary paintings.

This month, Keats, aged 22, resolves to escape the poetic and egotistical pinings

of his

contemporaries (William Wordsworth and Leigh Hunt in particular) for the more direct pleasure

of older poets and poetry. On this account, he may be taking the lead of his friend

Benjamin Robert Haydon but, more likely, the critic

and essayist (and acquaintance) William Hazlitt,

whose lectures on English poets he has recently attended (on 10 and 17 February).

To his

younger brothers Tom and George, he reports attending Hazlitt’s talks and seeing friends at them. Keats also mentions that Wordsworth recently left London—Keats met with

the famous poet a few times—but with his egotism, vanity, and bigotry,

he left a bad

impression

around town, yet he is a great Poet if not a Philosopher.

This clearly

captures one aspect of Keats’s deep ambivalence about Wordsworth as he attempts to

separate

the man from his work; this ambivalence is also rooted in Keats separating one prized

aspect

of Wordsworth’s poetic character from another he rebukes—genuine poetic depth that

explores

nature, loss, and shared human suffering vs trivial and self-indulgent topics channeled

through an overbearing subjectivity.

In a letter to his good friend John Hamilton

Reynolds written 19 February, Keats, perhaps in the spirit of escaping those

contemporaries, and with the beauty of the morning operating on a sense of Idleness,

explores the notion of indolence.

He turns his thoughts on the condition to suggest a

promising state closer to musing upon, wandering with, and positively enjoying a grand or

spiritual passage

of poetry or writing. Keats comes up with a poetically potent little

phrase—delicious diligent Indolence.

Keats’s playful musing ends with a rambling

attempt to portray human life, seeking, and friendships in extended metaphors of spiderwebs,

flowers, buzzing bees, and a grand democracy of Forest Trees.

His quasi-conclusion:

let us open our leaves like a flower and be passive and receptive.

In one way, this

clearly echoes the idea of wise passiveness

in Wordsworth’s poem Expostulation and Reply,

but it also

expresses a crucial concept for Keats: the imaginative ability to assume or become

whatever

comes to us—to patiently become the subject, and to let its complexity or simplicity

be the

guide to poetic expression, regardless of the conflicting, contradictory, or even

unknowable

nature of the subject.

Just more than a year later, during his extraordinary period of composition, Keats

massages

parts of these ideas about idleness and indolence into a good poem: Ode on Indolence. In working up to the

poem, the state as he describes it in a letter (19 March 1819) sounds something very

much like

meditation, with mind and body unbent as one: in this state, he writes, the fibers of the

brain are relaxed in common with the rest of the body, and to such a happy degree

that

pleasure has no show of enticement and pain no unbearable frown.