27 February 1818: Platonism, Axioms of Poetry, & Fine Excess; From Crawling to Toddling

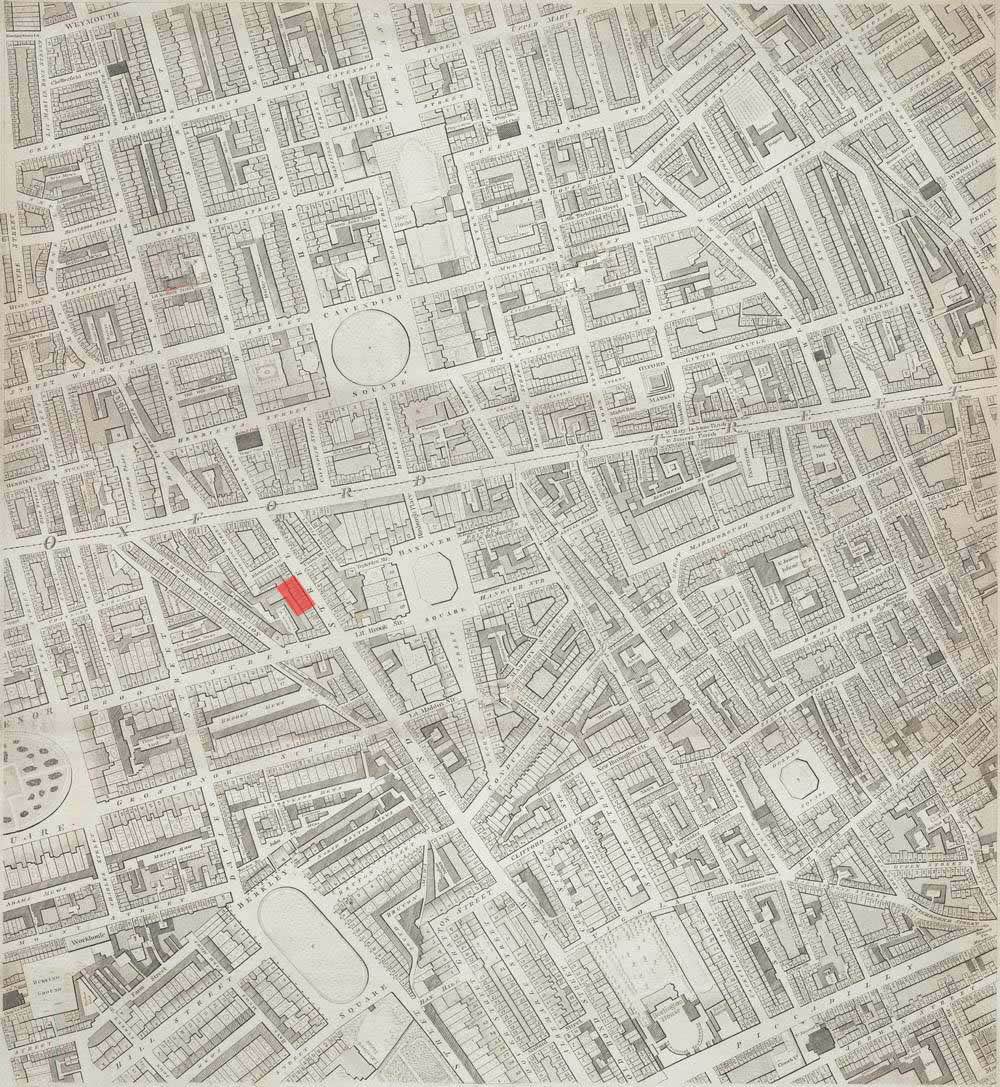

91 Bond Street, London

Keats writes to his publisher, John Taylor, at Bond Street. Taylor & [James] Hessey publish Keats’s Endymion (1818) and his last 1820 volume, and they also assume rights to Keats’s first volume, Poems, by John Keats, 1817. Taylor & Hessey will generate a loss on Endymion of well over 100 pounds. They will eventually pay Keats for exclusive rights of his poetry, and part of the money will be used by Keats to fund his trip to Italy.

At this time, in February 1818, Keats attempts to put the final touches on Endymion before

publication. Keats expresses he is extremely indebted

to Taylor for his editorial attentions on Endymion. Taylor, fourteen years Keats’s

senior, is confident of the inevitability of Keats’s poetic success, while he also

recognizes

Keats’s relative inexperience. For his part, Keats, as he copies out Book IV, is keen

to put

his poem behind him—it has, he writes, moved him into the Go-cart,

suggesting the poem

has taken him from crawling to toddling (a go-cart is a baby walker that assists a

child in

learning to walk). Despite this view of his own immature state, Keats feels his understanding

of Shakespeare is in fact mature. Keats

still has to write a preface for Endymion, but again, when he

does, it will reveal how Keats, over-apologetically, sees that the poem’s accomplishment

is

seriously compromised by his undeveloped poetic sensibilities. Keats is very keen

to publish

the poem so that he can, in his own words, forget it and proceed.

This is a good

self-assessment, and one needed if he is to genuinely progress.

Perhaps thinking of what Endymion does not achieve, to Taylor, Keats outlines three Axioms of Poetry: that it should surprise by fine excess and Singularity

; that its Beauty should be natural,

complete, calm, and yet leave the reader in the luxury of twilight

; and that if poetry does not come

naturally, it had better not come at all.

The phrase fine excess

as poetic goal and principle is particularly striking—and helpful; it captures the

idea of embracing and balancing the opposite qualities of impulse and control. And

this, in fact, may be key in understanding the nature of Keats’s achievement in his

greatest poetry, where intensity is measured by disinterestedness, and the vagaries

of truth are necessarily trumped by invariable beauty.

A few days earlier, 22 February, Taylor gets a letter from Benjamin Bailey, Keats’s friend at Oxford with whom he stays in September 1817. Views about Endymion are exchanged, and Bailey’s clear Platonic leanings about the eternal mind are expressed, which brings up the issue of Keats’s own Platonic leanings—or not.

No doubt Platonic ideas fall into Keats’s poetics and poetry, in part as a result

of his stay

with Bailey. It would, however, be stretching

things to suggest that Keats is a Platonist or Neo-Platonist—certainly not in the

way the

claim can be made for his fellow poet (and implicit competitor) Percy Shelley. No doubt many of Keats’s early idealisms

might render a quasi-Platonic reading; further, no doubt Keats’s ideas about truth

of beauty

(or beauty’s truth) suggests something like the mind’s perception of eternal forms.

But in

Keats’s best work, the material world in-itself is beautiful with or without the mind’s

idealisms; moreover, the eternal form that Keats seeks is, often enough, in the idea

of

enduring, great poetry. Complicating all this, though, is the role of imagination

in rendering

or representing some sense of eternal truth. A little like his senior contemporary

Samuel

Taylor Coleridge, in Keats’s conceptualizing,

a question works behind the scenes of Keats’s poetic creation: Is the Imagination

a faculty to

see Truths, or is the Imagination a kind of Truth in-itself?

At this point, Keats spends much time with Charles

Dilke and Charles Brown; he is sad that

his good friend Reynolds has been very ill; and

he is reading Gibbon and Voltaire. He has been

attending Hazlitt’s popular lectures, and he

notes that William Wordsworth, during the

month or so he was in London (during which Keats met him a number of times), left

a bad

impression because of Wordsworth’s perceived egotism, Vanity and bigotry—yet he is a great

Poet if not a Philosopher

(letters, 21 Feb 1818). In this final comment, Keats picks up

on the idea that Wordsworth’s poetry offers forms of deeper, meditative wisdom. Keats

may also

be calling upon the climax of one of Wordsworth’s key poems, the Immortality Ode, which dramatically moves to a remarkable moment that celebrates a

matured vision through the growth of the philosophic mind

(line 191). Keats is forcibly

struck by Wordsworth’s poetic accomplishment and vision, and he thoroughly engages

it in the

final two years of his writing. Keats remains less impressed by Wordsworth’s public

persona

and political values.