19 December 1814: Keats’s Grandmother Buried; All Family Elders Gone; Money Troubles Coming

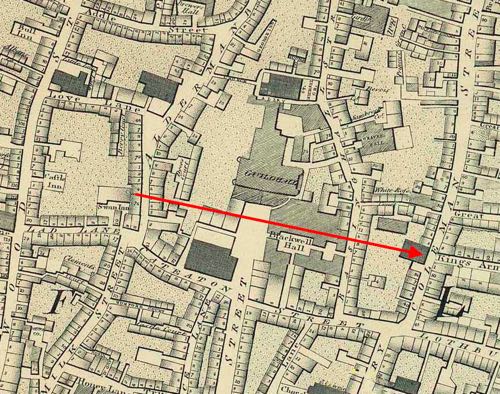

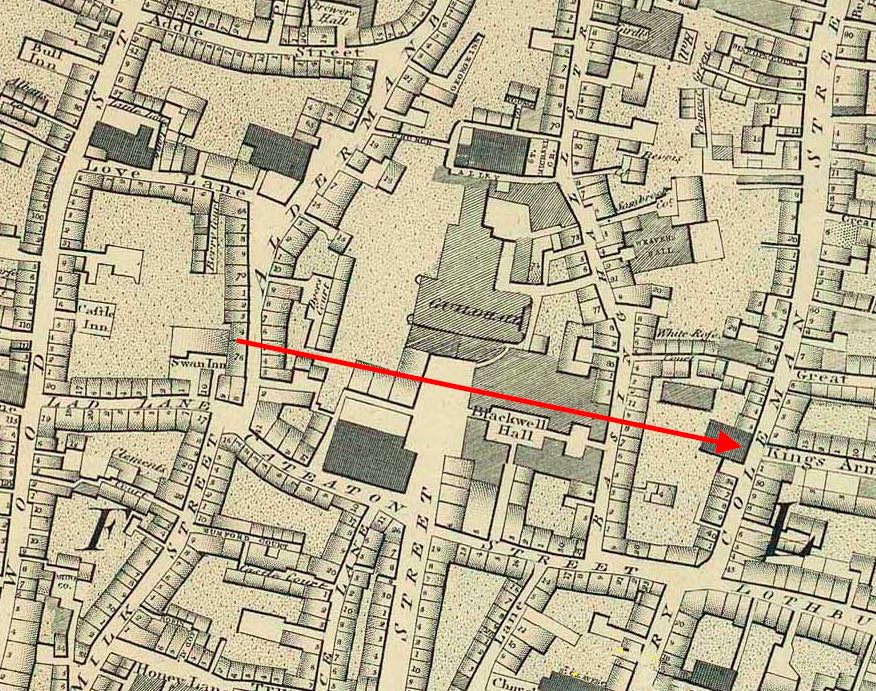

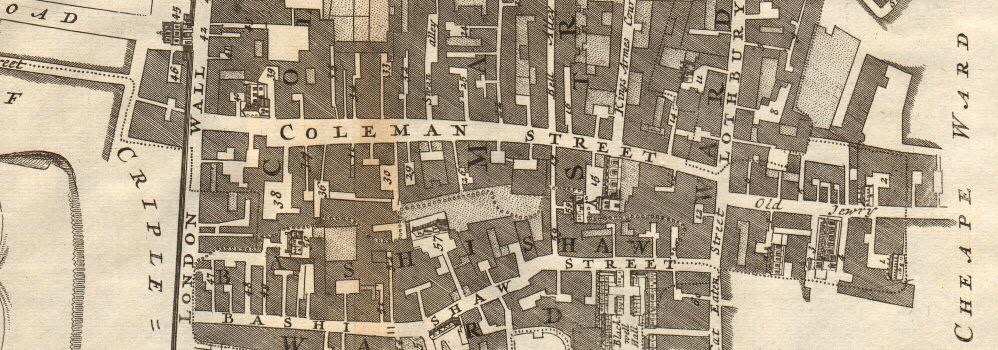

St. Stephen’s Church,* Coleman Street, London

Where Keats’s maternal grandmother—Alice Jennings—is buried, in December 1814. Keats greatly cared for her. Her passing represents the final falling away of his family elders, with both his mother and father already dead by 1814, and his maternal grandfather, John, passing in 1805.

In 1804, after the death of their father and the hasty remarriage of their mother, Alice took care of the children in Ponders End; and then, after the death of her husband, John, in March 1805, she takes the four Keats children with her to Edmonton. But where is Keats’s mother, Frances? Despite the vague accounts we have of her as an affectionate mother and talented woman, very hastily, and perhaps recklessly, she re-marries just over two months after the death of Keats’s father, leaving the children in Alice’s charge. After the failure of that marriage, and quite ill, she will return to the children at Edmonton; but, for her young children, she must have left some feelings of deeply-rooted and conflicted feelings. Keats will now care for her by helping with her medicines and meals, and by reading to her; sadly, he will watch his die in March 1810.

We see, then, how important the presence of grandma Alice had become for Keats and his yournger brothers and sister.

Late in 1814, Keats writes a poem in her memory of Alice—As from the darkening gloom a silver

bowl. This early attempt at a mourning sonnet pictures her soul fleeing into

the realms above,

where she will joinest the immortal quire.

Poetically, the

fragmentary soundings of Milton, as well as the

mixed and mixed-up images and feelings of gloom, delight, peace, love, happiness,

glory, joy,

bliss, and grief, are awkward and overwrought, but we can hardly deny Keats’s attempt

to

capture and elevate his deep memory of her.

Although relatively significant funds were to be distributed to the four surviving Keats children (money in a trust fund as well as some held in Chancery), the remaining guardian of the fund, Richard Abbey, is never perfectly clear with the Keats children about how much is available to them. And it turns out Abbey might not have been fully aware of all the legacy, since a fairly large sum (from Keats’s grandfather) was held in the courts, and when Keats is desperate for money (as he is in 1819), he has no idea of its existence.

Keats’s constant anxiety over money issues until his death might have been avoided with due diligence from Abbey, who was, quite understandably, skeptical about Keats’s decision to be a poet. But it is not all Abbey’s fault. Though very conscious of money, Keats often manages to spend freely whatever piecemeal funds he manages to drag from Abbey, though at times he has to borrow from friends. Part of the problem is that after leaving his medical training, he lives mainly on credit based on his inherited money (it seems he is never sure how much capital he has; full disclosure from Abbey might have helped). Keats, in short, does not budget well, and within a few years after turning away from medicine as a carer, he burns through the funds. He enjoys a few trips outside of London, but he especially enjoys much of what London has to offer, especially the theatre, the galleries, booksellers, exhibitions, dances, and dining with friends. He is also too generous in making loans to friends who might never repay him; loaning money you don’t really have is as reckless as it is admirable.

The family money that comes down to Keats is an important part of the story behind his poetic progress: without those funds, Keats would not have been able to pursue his poetic aspirations so freely—or even at all.

[For more on that contributes to Keats’s poetic progress, go to the factors page.]

*A note on St. Stephen’s: German forces bombed and destroyed the church in late 1940.

From

1959-1961, the remains of those buried there were exhumed and reburied in at Brookwood

Cemetery in Woking (also known as the London Necropolis; the cemetery dates from 1849).

This

process of relocation (which over time comes to include thousands of bodies from numerous

London churchyards) would have included reburial of the remains of most of Keats’s

closest

relatives: his mother and father (Thomas and Frances), his maternal grandparents (John

and

Alice Jennings), and his younger brother, Tom. Today, their graves remain unremarked.

Full

thanks to Julie Bozza for doggedly tracking down this information (mainly via the

London

Metropolitan Archives and Brookwood’s records), and for establishing that those reburials

are

located on the south side on Plot 70, St Agnes Avenue, behind what is now known as

Beard

Constructions; Plot 70 remains unmarked and overgrown. That the avenue is called St Agnes

is, from a Keatsian perspective, somehow

appropriate, given that the whereabouts and fates of the young lovers in Keats’s poem

of that

name remains an eternal unknown.