1 March 1819: Indolence Once More: Nothing—Nothing—Nothing

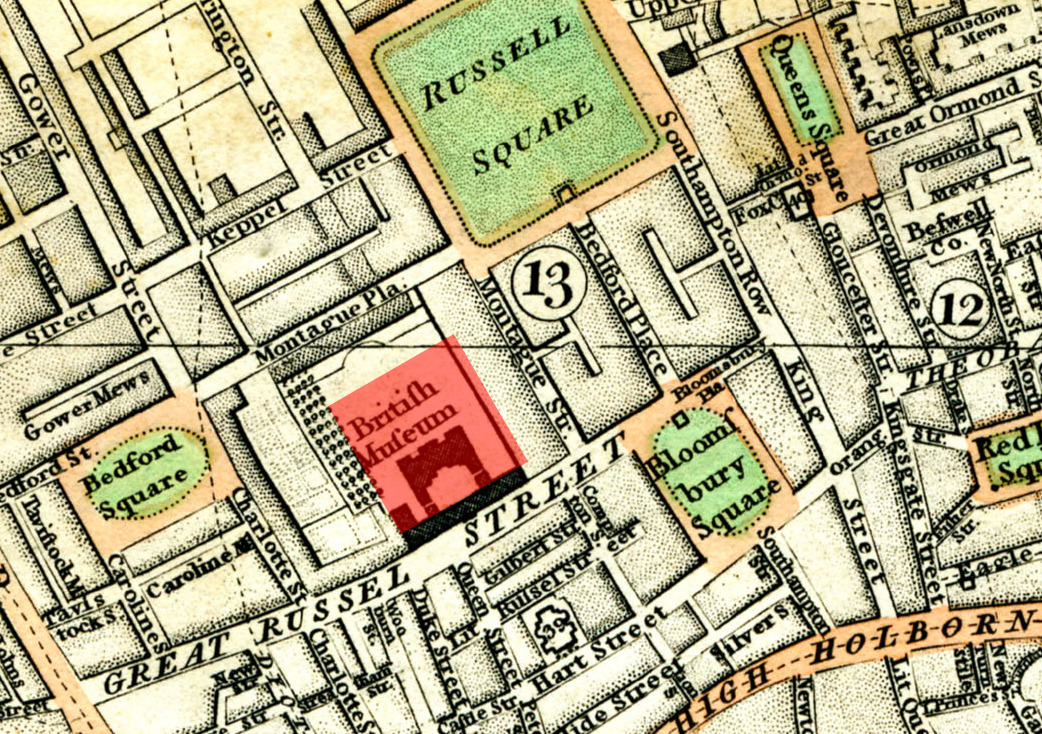

British Museum, London

Keats begins March 1819 with a morning visit to the British Museum with his friend, the young painter Joseph Severn, where they see a large and striking sphinx. Severn leaves us with a few images of Keats, including a miniature, a few portraits, and a sketch of Keats on his deathbed—and remarkable letters that describe Keats’s agonizing last months as he attempts to comfort and nurse Keats. After Keats’s death, Severn to a large degree attaches himself to (pairs himself with) Keats’s growing reputation. Severn will make sure that his own grave will be next to Keats’s. Keats ends the day going to the theatre with his very good friend and roommate, Charles Brown. He’s hardly the figure of the solitary, Romantic poet.

Throughout March and into April, Keats worries why his poetic progress seems to be

on hold.

Indolence

and idleness

—his own descriptions—plague him; he ponders

carelessness, languor, laziness, and even a mind-body state that today we might vaguely

recognize as transcendental meditation (letters, 19 March). He writes to his affectionate

and

encouraging friend, the painter Benjamin Robert

Haydon on 8 March, You must be wondering where I am and what I am about! I am

mostly at Hampstead, and about nothing.

Keats adds he is in a sort of qui bono

temper

—a kind of purposeless state, and not exactly on the road to an epic poem.

Keats resolves not to write for the sake of writing,

but only when he has something to

say that is tempered by extended reflection; he also expresses that he tires of the

vulgar

literary crowd. The comment on not being on the road to an epic poem

is a sideways

description of his difficulties in getting on with the Hyperion project.

Later in the month, 13 March, his worries continue: I know not why Poetry and I have been so distant lately. I must make some advances

soon or she will cut me entirely.

He nonetheless remains upbeat enough to put on an evening party.

Creative frustration: Keats says he cannot bear

any more unproductive days, even if he

is surrounded by friends and has social engagements: he walks with, dines with, smokes

a cigar

with, and hosts friends; meets with the guardian of the family estate to get money;

sees his sister; and receives a black eye playing cricket,

which is treated with a leech. But Keats’s frustration is heard in what he writes

to his

brother George and his wife: I do not know what I did on

Monday—nothing—nothing—nothing

(letters, 17 March). Keats even ponders making a return

to a medical career. Part of Keats’s problem is in fact progress he has made, which

now spills

over into his upward expectations. To Haydon he

continues: he is resolved never to write [poetry] for the sake of writing

; he will

remain dumb

until he has accumulated enough knowledge and experience,

which, he

believes, may take years. He knows, that at age 23, he has written a few fine passages, but

that is nothing.

In short, he will not write on anything unless it is a worthy subject upon which he

can write

worthily. This, then, is an important moment. There is a sense that he is, as it were,

primed

and stymied at the same time. In having worked hard at Hyperion, Keats recognizes the advance it makes in his poetic capabilities—acquired in

part through his deliberate parsing of the patterns and strategies of Milton’s Paradise Lost—yet he remains hampered by its direction and in

constructing a balanced, profitable scope for the poem—a scope that is his own. It

is, in

effect, his new standard, though it remains unfinished, and not quite in a style that

enthuses

or is natural to him. That is, what it has given him is simmering resolve: there will

be no

more inconsequential or occasional topics; no more romance; no more poetry about wanting

to be

a poet; no more mawkish

verse. To borrow metaphors of poetic development from the

preface of his own Endymion, Keats’s adolescent imagination has

fermented enough, and now the imagination of a healthy man needs to show itself. Although

he

still sees himself as a young writer, he determines that there is merit in straining at

particles of light in the midst of a great darkness—without knowing the bearing of

any one

asserting of any one opinion

; so, once more, Keats recognizes that there is strength and

even beauty (those particles of light

in great darkness

) in uncertainty, and

that becomes his pursuit: this is, in great part, the very thing in which consists

poetry

(letters, 19 March). It is the profound, unavoidable Wordsworthian burden of a

mystery that we all carry; it is Shakespeare’s remarkable ability to reach for great beauty in the unreachable.

Keats’s calculation about needing years to accumulate knowledge and experience to be among the greats is, thankfully, wrong. Within a matter weeks, rather than years, Keats’s writes poetry that makes a huge qualitative leap, so much so that it is commonplace to look upon Keats’s rapid development as one of the most striking creative feats in English literature. And though this leap in Keats’s poetry carries the air of enigma, we have seen how complex conditions and intertwined factors in fact point to the extraordinary poetry of 1819. Keats himself willfully anticipates it, largely in his poetics. We can read backwards into and through Keats’s statements about poetry, the poetic character, the imagination, and beauty, with the following motivational lens: This is the poet I need to become; this is the kind of poetry I need to write. And then he does it.

*For more on Keats’s medical training, see 15 October 1815.