29 March 1819: Joseph Severn’s Miniature of Keats; Art, & Loose Ends

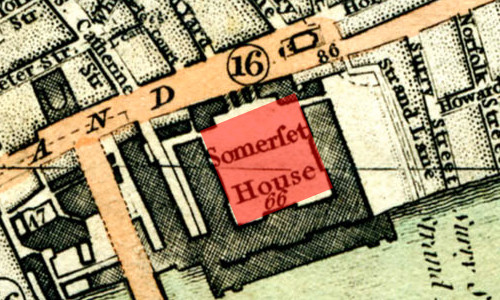

Royal Academy (Somerset House, the Strand), London

Keats’s friend, the young artist Joseph Severn (who is about two years older than Keats), wants to exhibit two paintings at the Royal Academy in March 1819, one of which is a miniature of Keats. Keats asks Severn that it not be displayed, but Severn clearly wants it to be seen. Later in the year, in December, Severn, as a student, is awarded a gold medal by the Royal Academy for his work.

In an attempt to revive Keats’s failing health, it is Severn who, in September 1820, makes the abrupt decision to accompany Keats to Italy (Severn’s exit is perhaps also motivated by a recent illegitimate child). Severn selflessly cares for Keats until Keats’s death in Rome, 23 February 1821. Severn’s accounts of Keats’s illness and passing are the only significant account we have of what Keats goes through during this period. Much if not all of Severn’s fame comes to rest on his association with Keats (Severn openly capitalizes on this). Severn remains an active painter and exhibited throughout his life. In 1861, Severn is appointed Counsel in Rome. His wish was to have his grave beside Keats’s, where it can be seen today.

Severn is also important inasmuch as he knows

art and London’s art scene very well. Severn goes with Keats to exhibitions, and he

plays a

role in furthering Keats’s interest in and knowledge about art, which profitably filters

into

Keats’s poetics and poetry. For example, Keats gets one of his key ideas about the

qualities

of great art by parsing what is lacking with a certain painting he sees: he concludes

that a

work can be pleasing, but if there is nothing to be intense upon,

if there is nothing

to excite depth of speculation

and make all disagreeable evaporate,

then it

remains incapable of approximating Keats’s key and conflated quality of Truth &

Beauty

(21/27 Dec 1817). This is the kind of response that Keats, ideally, will hope

that his own poetry will solicit. Paradoxically, what gives a work truth is its exploration

or

representation of surmise, uncertainty, and wonder.

That another of Keats’s closest friends, Benjamin Robert Haydon, is also a committed artist with much to say about art, confirms the role it plays in Keats’s progress. A turning point for Keats’s thinking about art’s grand potential comes when he sees the Elgin Marbles with Haydon in March 1817, which results in two of his better earlier poems, On Seeing the Elgin Marbles and To Haydon with a Sonnet . . .. The dizzying grandeur of the Marbles leads Keats to contemplate the meaning of mortality in the face of such artistic achievement and enduring wonder.

At this time, in March 1819, at twenty-three, Keats is, poetically, at loose ends. He has some doubts about his future and how he will support himself—and he should, since he has been living on credit for the last few years, and it is running out. While Keats wants to write, he does not want to compose for the mere sake of writing. Indolence (a state that both intrigues and frustrates him) is the best way to describe Keats’s temperament, especially because for Keats its emotive quality slides into philosophical and creative considerations.

Keats expresses that he no longer admires his former mentor, Leigh Hunt, and only half

of William Wordsworth (letters, 3 March). The idea of

disinterestedness of Mind

still guides his critical principles, even as he turns the

idea upon an understanding of society (letters, 19 March). This, too, is consistent

with his

poetics when, for example, he disapproves of Wordsworth’s poetry of subjectivity and

egotism,

and perhaps what often seems to be Wordsworth’s inconsequential subjects—writing for

the sake

of writing, which Keats says he will no longer do. Keats also notes that while Hunt

and

Wordsworth are two most opposite men,

they are the same in that, at least in

conversation, they seem to be more interested in making an impression than in genuine

searching for knowledge (letters, 8 March).

These kinds of statements, ideas, and sentiments, made in light of his influential

contemporaries, represent Keats’s determination to strike an independent path. At

the same

time, Keats does admire the tastes, tone, and critical observations of his friend,

the

literary critic and essayist William Hazlitt

(letters, 3, 13 March), from whom he engagingly borrows ideas about Wordsworth’s qualities and shortcomings, as well as the nature

of Shakespeare’s genius. But he still cannot

shake that other half

of Wordsworth’s exceptional achievement, the half that explores

the heavy burden of loss and suffering in the face of permanent forms that surround

and

impress.