25 March 1819: Straining at Particles: A Temperament of Disinterestedness

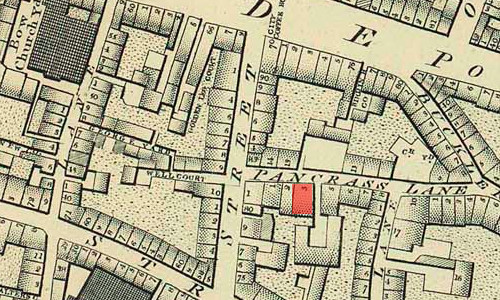

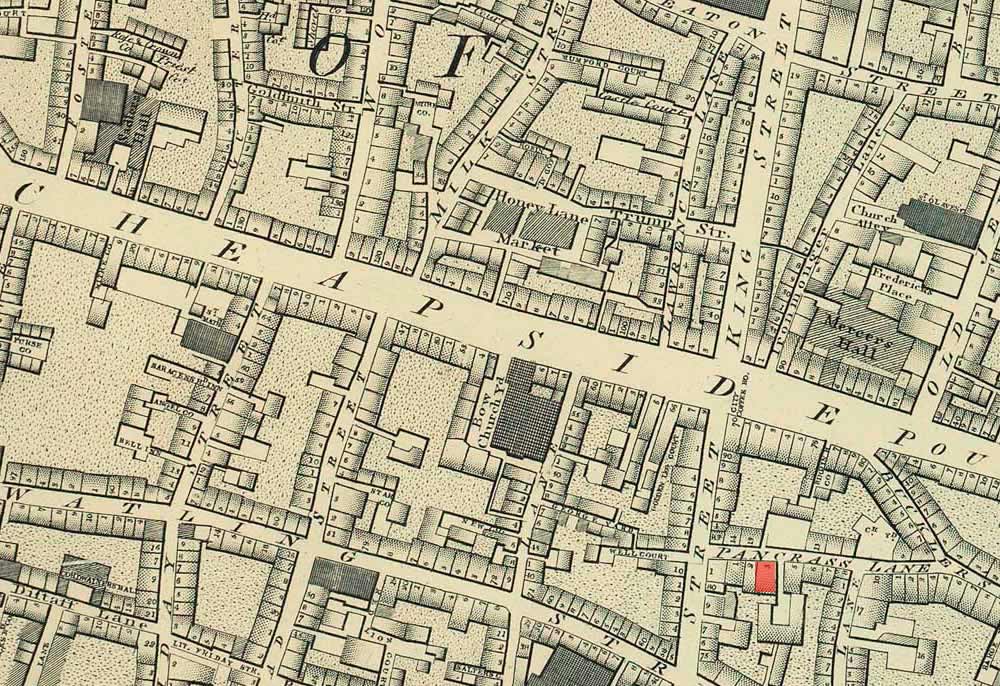

4 Pancras Lane, London

Keats sees his younger sister, Fanny, at 4 Pancras Lane, the residence of Richard Abbey, the family guardian and trustee. He manages to get 10 pounds from Abbey—money likely generated from interest out of dwindling capital from family inheritance.

Keats, aged 23, has been and continues to be very concerned that Abbey discourages Fanny’s contact with Keats, and that Abbey has taken Fanny has out of school. (Early on, Abbey believes Keats’s decision to be a poet is ludicrous, and is at times suspicious of the young poet.) With his parents dead, his brother Tom recently passing away, and the emigration of his other younger brother, George, to America, Keats’s family world—one that he valued exceedingly deeply—is narrowed. For us, though, George’s emigration to America is a windfall: Keats’s numerous long journal-letters to George and his wife Georgiana provide extraordinary and continuous insights into Keats’s habits, ideas, turns of thought, and friends—into daily, mundane details; playful speculations and observations; and the larger philosophical sweep of Keats’s ruminations about life, society, and poetry.

Besides being a month of general indolence with worries about lack of any recent poetic

progress, those personal finances, as mentioned, continue to plague him—not just his

own, but

those of his close friend, the historical painter Benjamin Robert Haydon, who has fallen on difficult times. In the last few months,

Haydon has asked Keats for a loan, which Keats first denies, and then (mid-April)

concedes him

30 pounds—money that Keats could badly use. As one of Keats’s closest friends, Richard Woodhouse, will note later in the year,

I wish he could be cured of the vice of lending—for in a poor man, it is a vice

(31

Aug).

By the middle of March, Keats develops a train of thought that rephrases and reinforces his earlier poetics of negative capability, the camelion poet, the Keatsian balance of disinterestedness and intensity, and the Wordsworthian-inspired exploration of the one human heart.

At one moment in his long letter journal to George and Georgiana (14 Feb-3 May),

these ideas assume a meandering yet philosophical edge; further, there is enough directed

substance running through these ideas to recognize them as precursors to what will

soon take

place Keats’s poetical practice (letters, 19 March). The fundamental premise in Keats’s

thinking is that everything that proceeds from human life and circumstance is uncertain

and

mutable. People move through this thing called life, looking for a pearl in rubbish.

There are, however, a few great persons who move with and look upon life’s uncertainties

with

both fine disinterestedness of heart and unresolvable speculation. Keats, seeing himself

as a

poet straining at particles of light in the midst of a great darkness

without any

bearing,

clearly values the strength of and imaginative potential in such a state, in

the face of the unknowable and unpredictable. Keats, in striving to know himself,

believes he

has a temperament

and speculative Mind

able to cope with and poetically reflect

the paradoxical nature of that condition; this, again, provides an important backdrop

to his

imminent poetic progress.

These ideas fall back even further into some of Keats’s earliest developing formulations about poetry—that it should act in an indeterminate way, that it should be unobtrusive, that it should be, as it were, natural. Very shortly, Keats’s poetry in fact strikes this balance where not-knowing and uncertainty are creatively forceful and, paradoxically, equable conditions.

One thing we learn about Keats’s poetic development: his poetics precedes his poetic progress. In a manner of speaking, his poetic process is, relative to his poetics, profitably ad hoc.