25 December 1818: Fanny Brawne’s Ways, the Hyperion Project, & Greatness in a Shade

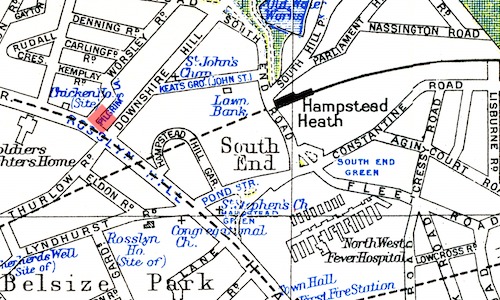

Elm Cottage, Hampstead

Elm Cottage, Hampstead: Where the Brawne family lives—not far away from Keats at Wentworth Place, where he lives in one half of the double-house with his very good friend, Charles Brown, who is co-owner of Wentworth Place.

When Keats first meets Fanny Brawne, aged 18, is not perfectly clear, but was probably not long after Keats returns from his northern walking tour with Brown, mid-August 1818.

Keats spends some of this Christmas day with the

Brawnes, though he makes a social faux pas by accepting two invitations for

Christmas. There is also a vague but unsupportable suggestion that Keats and Fanny are unofficially engaged on Christmas day,

since a few years later Fanny recalls it as her happiest day.

This could mean anything,

including a simple mutual declaration of love or a first kiss. Keats also has dinner

with the

Brawnes on New Year’s Day, 1819.

Fanny, with her interest in dances and fashion, and her fairly open flirtatious and witty ways, tends to confound and even madden Keats; when Keats in 1820 sinks into illness, it eventually makes him irrationally jealous. Her interest in clothes and appearance may have come from the fact that her uncle was the age’s most famous male fashion icon, the dandy Beau Brummell. Generally missing from assessments of Fanny is that she was in Keats’s eyes not just beautiful, but also bright, full of life, and testing of Keats’s opinions; there were, then, many reasons for Keats to be attracted to her. Keats’s love for Fanny grows into the new year and beyond, but the complexity of his circumstances—his dedication to poetry, his love of solitary thinking, his wavering health, stretched finances, the negative opinion of her from some of his friends, and hesitancy about Fanny’s suitability—place much pressure on the relationship.

In December, as Keats thinks over attacks made on his very long (too long) and largely unconvincing poem Endymion (drafted April-November 1817, published spring 1818); and as he criticizes Leigh Hunt, his friend and former mentor, for over-aestheticizing things otherwise fine and beautiful (and also for his perceived egotism), Keats works hard to get on with his lingering and serious project, Hyperion. Now and into the new year Keats puts demands upon himself for a controlled, elevated style and idiom, and thus the poem remains a working ground for Keats to practice and find some experience in the expression of a mature poetic voice. Hyperion, though, with its two incarnations (The Fall of Hyperion and Hyperion: A Fragment), remains unfinished and unfinishable, but the project is important inasmuch as it keeps Keats working at poetry, and thus his mind, body, and spirit remain (temporarily) enthused and, just as importantly, occupied. The result, although a fragment, is somewhat astonishing: though for readers the poem’s sympathies are complicated and uncertain, Hyperion’s restrained tone and style place it substantially above anything he has written; in terms of Keats’s poetic progress, it puts into clear perspective the relative immaturity of Endymion.

Keats has also begun to recognize his own vices as a poet,

which reduce to the touchy

desire for fame and admiration, though he also more maturely begins to shun these

in favor of

solitude and hidden or quiet achievement—greatness in a Shade,

he calls it (letters, 22

Dec). The wonderful metaphor reminds us of a few things: Keats’s humility; his conception

of

the camelion

poet, one without a defined identity; and, yet, what remains is Keats’s

continued desire for and confidence in attaining poetic greatness.

Keats’s chronic sore throat continues to bother and sometimes confine him, and this continues into January and February 1819. This does not bode well. But by the end of 1818, it is fully clear Keats’s poetic theory is in place; now he has to write the poetry.