7 December 1818: Tom’s Burial, The Vice of Lending, & the Imperative to Work, Read, Write

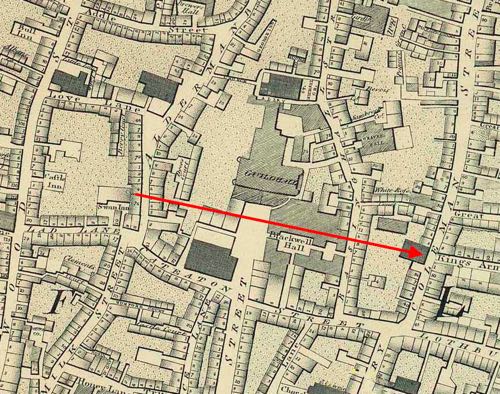

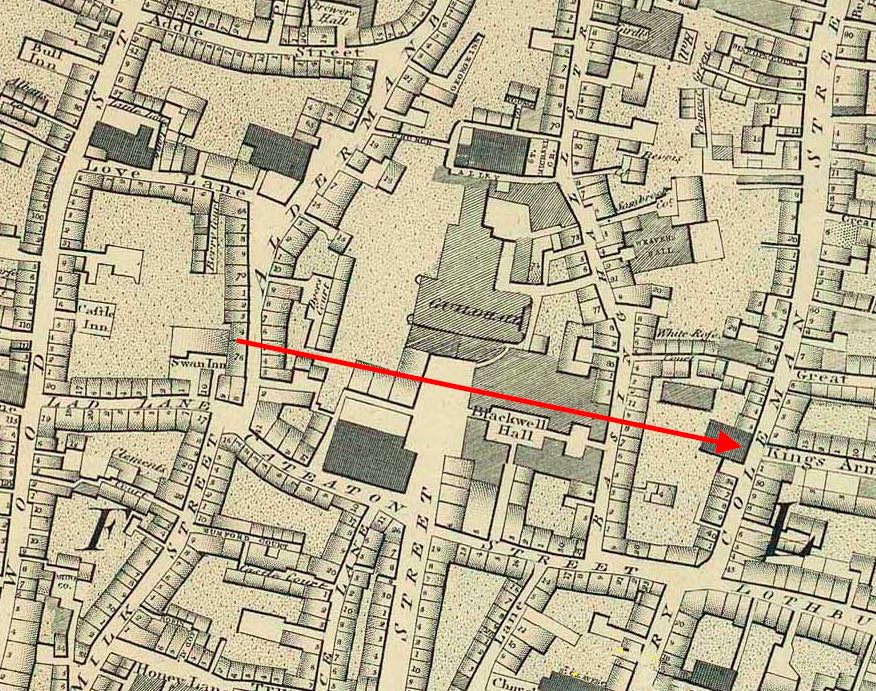

St. Stephen’s (church), Coleman Street*

Keats’s youngest brother, Tom, is buried at St. Stephen’s 7 December, a week after he dies of consumption. Since returning from a walking tour (mainly through Scotland) mid-August, Keats has watched over Tom. At the invitation of his friend Charles Brown, Keats moves into half of Wentworth Place in Hampstead, which is a double-house. [See 23 April 1804 for a note on the fate of St. Stephen’s and the Keats family graves.]

Caring for Tom has been extraordinarily demanding—physically and psychologically. Keats’s own lingering health problem—a chronic sore throat, for which he may have taken a little mercury in the form of a cream—continues to trouble Keats now and into the new year. He had in fact curtailed his walking tour because of his illness.

Tom’s death is both a relief and a stark

reminder of his own life’s course and present situation: Keats’s parents passed away

when he

was still young; his other younger brother, George, has moved to America; and his younger sister, Fanny, is (for the lack of a better term), tightly managed

by the family trustee, Richard Abbey, who protects

her from the sway of her brothers, and especially Keats. Keats does, nevertheless,

get to see

Fanny on at least three occasions in December.

Abbey is also the guardian of the Keats financial estate, and he often seems to keep the brothers in the dark about family money, which is now made more complicated by Tom’s death. The situation will become more complicated when George returns from America in January 1820 to re-finance his failing business ventures in America. Keats is himself constantly desperate for money, and at moments Abbey appears equally desperate not to give him any. Then again, Keats had used up a good portion of his inheritance money by October 1816, when he turned twenty-one, and much of it on his medical training; Keats subsequently had to live off credit based on the remaining funds—but this could only last so long, since it is clear Keats is spending more than the credit renders him.

This month finances are a nagging issue since he asks for money from one friend, while

another asks Keats for a loan—and he did get some cash from Abbey (20 pounds) just

after Tom’s funeral. That Keats is in the habit of loaning money out to friends is

also hardly prudent: as his very good friend Richard Woodhouse puts it when it becomes

absolutely clear that Keats is in financial despair, I wish he could be cured of the vice of lending—for in a poor man, it is a vice

(31 Aug 1819).

Keats’s personal itinerary shows that his friends keep him busy with dining engagements,

the

theatre, socializing and visiting, a few minor outings, and even some shooting (he

manages to

kill a little bird—not a nightingale, one hopes). But Keats also comes to see this

month that,

in order to get on with his poetry, he needs to put a damper on his socializing; Keats

quips

that the rules of society

actually make him look like an Idiot

(letters, 18

Dec). His work on a potentially great poem, the Miltonically-toned Hyperion, moves slowly, but he knows he needs to reform and apply himself to achieve

any poetic progress; as he writes to his friend Richard Woodhouse on 18 December, I have a new leaf to turn over—I must work—I

must read—I must write . . .

This self-motivation carries some positive prediction,

since Keats is on the verge of his only period of compositional greatness—1819.

*For a note on the fate of St. Stephen’s and the Keats family graves, see 23 April 1804.