5 December 1818: A Magnificent Prize Fight, & Keats as the Brightest Ornament of the Age

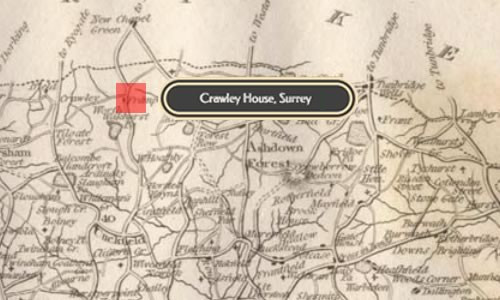

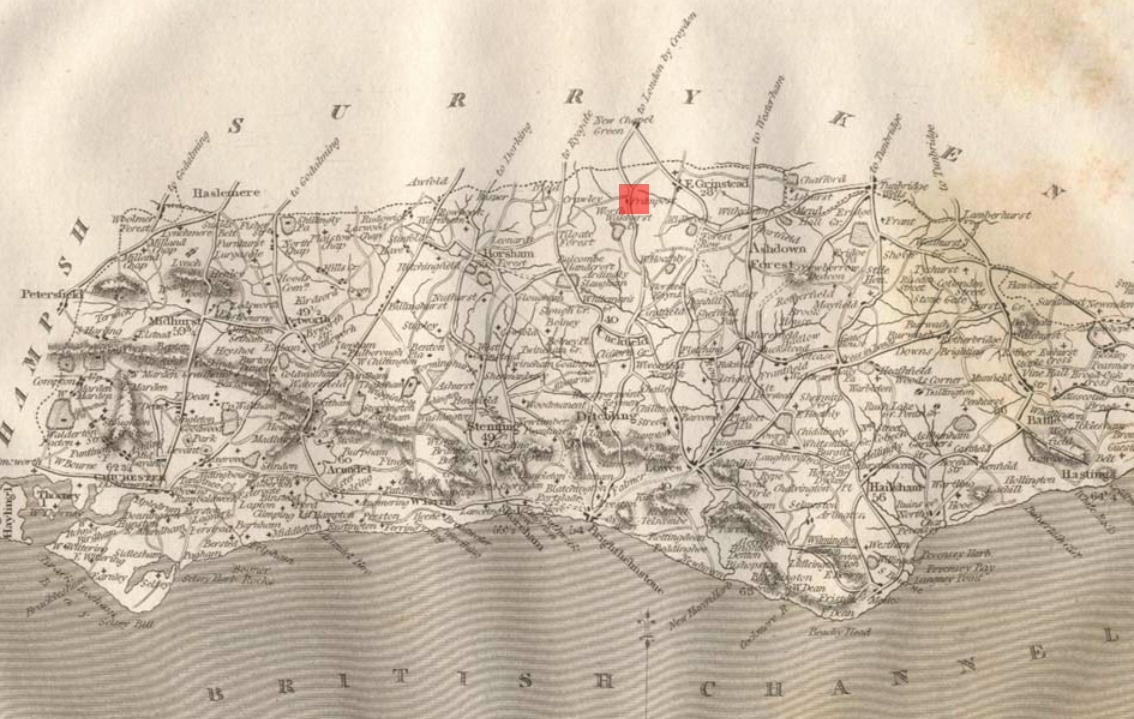

Crawley Hunt (or Crawley Down), Sussex

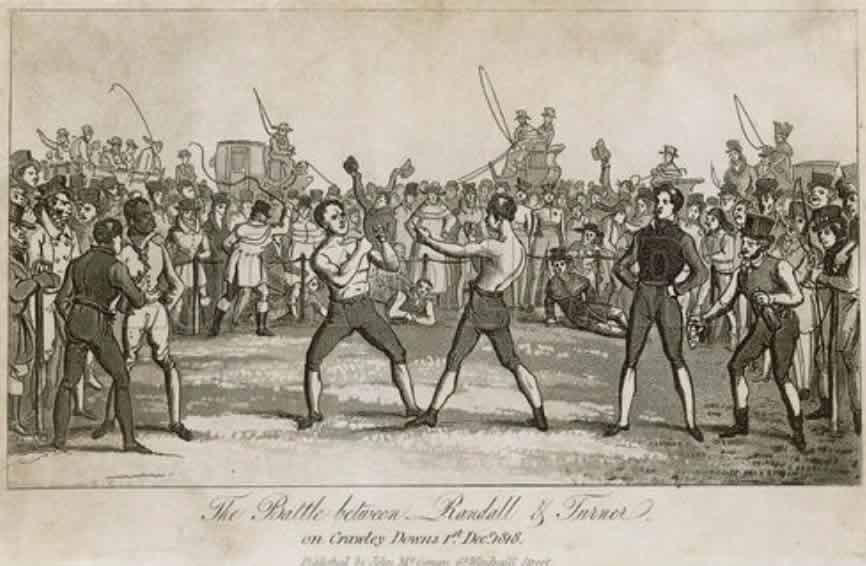

Keats watches the famous prize-fight between Ned Turner and Jack Randall (a.k.a. The Nonpareil

) on Saturday, 5 December.*

As one sports writer records the fight, the amazing struggle

lasts no less than two

hours, nineteen minutes, and thirty seconds

—34 rounds—with Randall (16-0-1) the victor. The match may have been the most

betted-upon event of the era. Perhaps going to the event was intended as a diversion

(and

release) for Keats from the recent death of his younger brother, Tom, on 1 December, as his friends rally around him.

Keats struggles to make some progress with his largely Miltonic Hyperion during this period, and it remains a fragment that overlaps with and then falls into the extraordinary period of composition that begins spring 1819. He gives up Hyperion in April 1819, attempts to return to the topic again, later, in July 1819, yet gives it up once more by September 1819.

Hyperion nevertheless remains a substantial step forward in the direct application of Keats’s developed poetics. The topic as he approaches it prescribes the commingling of intensity with disinterestedness in an elevated, controlled style, and without any of his early poeticisms and wooly affectation. Keats said he always wanted to return to Greek mythology after earlier failings to represent its beauties, and so in a way Hyperion can be viewed as an attempt to both cancel and correct the foggy accomplishment of Endymion, published in 1818. But despite the clear advance in Keats’s poetry—putting Endymion and Hyperion side-by-side makes this absolutely clear—Keats seems to struggle with the narrative’s momentum in terms of what exactly to do with the Titans, and in particular what to do with their motives and fate. The conflict between Hyperion and Apollo in particular seems to stymie him. And, of course, always floating in background is the intimidating presence of Milton’s Paradise Lost. Is he sounding too much like Milton? Keats likely begins to feel that the more reserved style of his epic does not tap into or represent the complexities of his growing lyric impulses, which begin to show in early 1819.

At this time, Keats’s friends remain supportive of and confident about Keats’s poetic gifts, including, but especially, John Hamilton Reynolds (poet and critic), Benjamin Robert Haydon (noted painter and passionate supporter), Richard Woodhouse (lawyer and scholar), and Charles Wentworth Dilke (civil servant and scholar).

On this day, in fact, another friend, John

Taylor (Keats’s publisher), takes the trouble to write to the influential Sir James Mackintosh: Taylor believes Keats is a

real Genius,

and though he notes that the flaws in Endymion are many, Taylor believes Keats’s gifts and potential will no doubt make

him the brightest ornament of this Age.

This is quite a proclamation—made with complete

seriousness—and it turns out Taylor is right.

* The fight had first been scheduled for 1 December, but the death of the much-loved Princess Charlotte, aged twenty-one, on 5 November, followed by a massive public funeral and two weeks of mourning, put the event back; her death was caused by a still-born birth complicated by very poor medical treatment.