27 December 1817: Things Dovetail after a Disquisition: the Negative Capability Letter

Thinking Back to the Night Before

27 December 1817: Keats, in Hampstead, is finishing off a letter to his younger brothers, George and Tom. Part of the letter describes the evening before, when, with a couple of good friends, Charles Brown and Charles Wentworth Dilke, he sees a Christmas pantomime at Drury Lane theatre (Theatre Royal), where it runs for about a month. There is nothing unusual about the outing; after all, Christmas pantomimes are, at the time, and with their outlandishness and stage trickery, very popular.

December 1817 has been a very busy month for Keats. He’s been wining, dining, visiting, attending exhibitions, and going to the theatre. We can say that, as a Regency London lad, Keats is hanging around in a fairly large, interesting circle, and clearly taking it all in. That is, Keats is anything but a version of the solitary, pining Romantic poet pondering his ponderings in leafy nooks. We have to keep in mind that Keats really hasn’t done much yet as a poet besides publish a collection of early poems eight or some months earlier that border on juvenilia, so the fact that Keats has access to and a place within that social circle (of generally older and more established figures, and in mainly liberal circles, beginning with Leigh Hunt back in October 1816) says something about Keats’s personality and his perceived potential.

But the outing on the evening of the 26th is more than just another social romp for Keats: he has a purpose in seeing the production, since yet another close friend, John Hamilton Reynolds, has asked Keats to take his place in writing a review of it (Reynolds is off to Exeter, perhaps to do a little courting). The play—or harlequinade—is Harlequin’s Vision; Or, The Feast of the Statue, which runs for about a month.

Immediately after seeing the performance of Harlequin’s Vision (with perhaps as many as 3,000 others in the audience), and while walking with Brown and Dilke back to Hampstead through London, they almost certainly discuss what they have just seen, especially given that Keats was going to have to write something about it.

So what had they just seen?

Accounts of Harlequin’s Vision suggest that it was a rollicking mash-up of elements and qualities: more action than plot, highly whimsical, full of odd and arresting transformations, a bit gruesome here and there with splashes of vulgarity, outrageously juxtaposed scenes and sets, a great deal of over-the-top and chaotic gesture, noisy, a cloudy mix of dream and reality, boggling visual proportions, and punctuated by vaguely related songs (which allow for the elaborate set and costume changes). There’s apparently even a real horse on stage. The whole thing sounds a little crazy, though fun. If it was anything like pantomimes of the era that we know more about, it was unafraid to challenge and mock not just stage conventions, but the audience itself.

Meanwhile, back at the moment before “Negative Capability” actually appears in the letter: that late-night, after-play walk with Dilke and Brown leads to an exchange with Dilke. As Keats describes it in his letter likely written on the 27th,

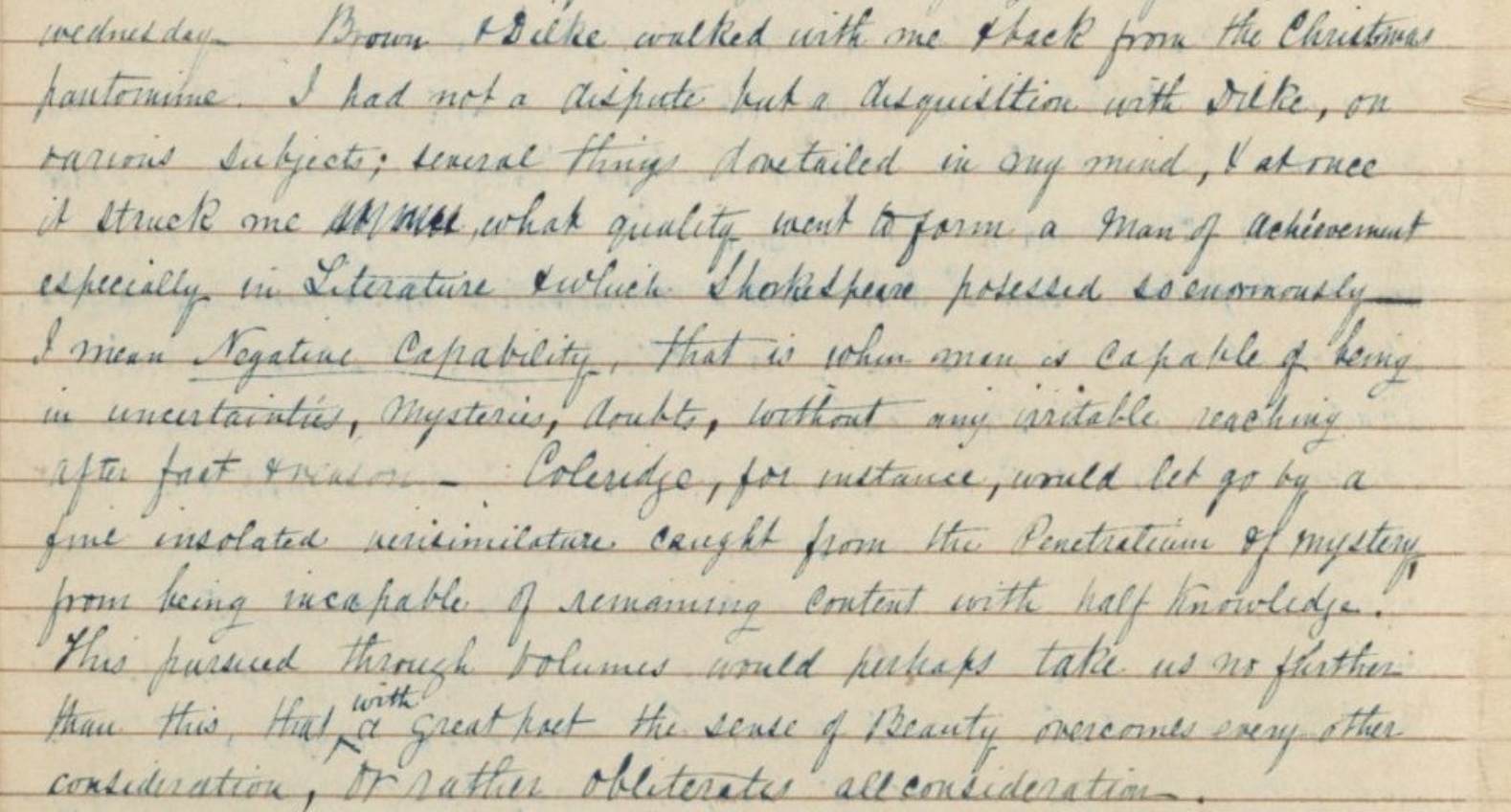

Brown & Dilke walked with me & back from the Christmas pantomime. I had not a dispute but a disquisition with Dilke, on various subjects; several things dovetailed in my mind, at once it struck me, what quality went to form a Man of Achievement especially in Literature & which Shakespeare possessed so enormously—I mean Negative Capability, that is when man is capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact & reason—Coleridge, for instance, would let go by a fine isolated verisimilitude caught from the Penetralium of mystery, from being incapable of remaining content with half knowledge. This pursued through Volumes would perhaps take us no further than this, that with a great poet the sense of Beauty overcomes every other consideration, or rather obliterates all consideration.

Since we don’t have the original letter to Tom and George, there are a few problems. What we do have is a somewhat uneven version as transcribed in 1845 by John Jeffrey (a Scottish engineer and the second husband of George’s wife, Georgiana), who discovers that a life of Keats is being put together by Richard Monckton Milnes (published in 1848). For example, it is not clear if Jeffrey copies all of the original letter, or if he changes some wording, spelling, or things like capitalization; he also gets the date of the letter wrong by a year. But, in a way, no matter, even if we do know that his other transcriptions are unreliable. What we have in Jeffrey’s hand in this case does fully sound like Keats in his some of his other letters, where, in pressing his ideas, his tone is not just confident but almost manifesto-like. The passage in the letter also fully picks up on Keats’s developing reasoning about poetical qualities he aspires to enact in his poetry. Here Keats’s pursuit is clear enough: to become “a great poet.” We have to consider, too, that the letter is written for his brothers, who are not just very close to him, but in awe of their older sib’s aspirations and intellect.

But let us imagine the immediate context. The walking conversation between Keats and Dilke, which almost certainly begins with discussing Harlequin’s Vision, “dovetailed” into other related literary topics, quite likely because they are talking about the merits, qualities, or even mystifying or inexplicable meaning of the pantomime. Is its meaning doubtful? Does it need to be fully understood as a requisite for some kind of imaginative authenticity?

Dilke and Keats perhaps disagree about something (Keats barely resists calling it

a

“dispute”), but Keats takes some care to describe the style of their discussion: “a

disquisition,” he calls it. The term, a little formal, suggests a fairly vigorous

explorative

or extended dialogue between the two friends. And we have to believe that Dilke was

not an

uninformed, passive partner in all of this; after all, he is older than Keats, and

he is the

editor of a recently published multi-volume collection entitled Old English Plays. In

short, Dilke has a scholarly-critical turn, and he knows something about drama and

dramatic

theory. He likely presses or challenges Keats’s thinking. Dilke is opinionated, and,

in

Keats’s own opinion, someone without a sense of identity unless he has made up his Mind

about every thing,

which is the opposite of what Keats formulates with negative

capability.

In the course of the discussion as described in the letter, Keats, points to his epiphanic moment; he writes how he is suddenly “struck” by the idea. If Jeffrey’s transcription can be vaguely trusted, this is even more pronounced since Keats capitalizes and underlines the term that encapsulates what he’s attempting to describe: “Negative Capability.” That Jeffrey possesses the critical acumen to emphasize the term is not likely; he’s just copying—quickly—while likely making some editorial changes and taking shortcuts along the way, as well as creating some errors.

The term itself and the thinking to and then beyond it is central to Keats’s poetical

development. It pushes forward other thoughts about the kind of poetry he wants to

write and

the kind of poet he wants to become. Since March, he has stated that he is determined

to

improve himself; he has questioned why he, more than “other Men” should be a poet

(letters, 10

May 1817); he knows he has to conquer his emotional lows; he knows he must come to

critical

terms with the likes of Shakespeare, Wordsworth, and Hunt; he knows he has to discursively explore and then poetical

enact the complex connection between beauty and truth, and the role that the imagination

plays

in bridging the two (letters, 22 November); and he also knows he has to complete and

put

behind himself the long poem—Endymion—he has been working on since April. And early in the new year, in

continuing his thinking, Keats will be able to write, Poetry should be great &

unobtrusive, a thing which enters one’s soul, and does not startle it or amaze it

with

itself but with its subject

(letters, 3 February).

Keats’s theory when parsed beyond his immediate context is, at bottom, both aesthetic and philosophical—and in the case of the latter, it certainly hedges toward sceptical philosophy, inasmuch as truth as a reasoned end is ultimately unsupportable. He strives for a sense of understanding beauty in art, but he also speculates upon how it is we know and what constitutes truth. Keats manages to bridge notions of passive reception and active engagement: perception and sensation come (as it were) in, but what goes out is the individual imagination, which is now a tool of greater sympathy. What delights Keats is the wonderful paradox: that not-knowing is the most profound and creatively potent way to know; this, for Keats, constitutes poetic knowing and the poetical character. Thus poetry’s power, fueled by the unlimiting, ever-mutable imagination, marks a release from the confines of reason, and it trumps even values—except beauty. The ego cannot hold if, as Keats desires, the poet wants to enter subjects beyond himself.

One critical narrative that takes us to Keats’s thinking at this point is inflected by his reading of William Hazlitt, whom he begins to mention earlier in the year. And after the summer, while visiting with Benjamin Bailey at Oxford, we see Keats digging deeply into Hazlitt, via Hazlitt’s drama reviews, the Round Table collection, An Essay on the Principles of Human Action, and (later) his lectures. It is not just Hazlitt’s literary tastes and intellectual energy that Keats comes to continuously admire, but, more specifically, Hazlitt’s philosophical views on knowing and the imaginative capacities of sympathy; on how the subject can be known and rendered by a fusion of disinterestedness and intensity (that is, not by self-interest), as a form of submission to that subject. For Hazlitt, great work does not insist on anything, except perfection of form. These views will underwrite, first, Keats’s poetics, and second, later, his best poetry.

At this point, then, Keats’s progress is mainly through his poetics rather than his poetry. Moving beyond mere issues of fame (which initially hampers Keats’s thinking), Keats now comes to more fully comprehend exactly what he needs to effect in his poetry—a complete synthesis of language, thought, and feeling—which, as he writes in the negative capability letter, will in its controlled intensity make “all disagreeables evaporate.”