24 April 1817: Toward Endymion, the Temple of Fame, & Why I Should be a Poet

Margate

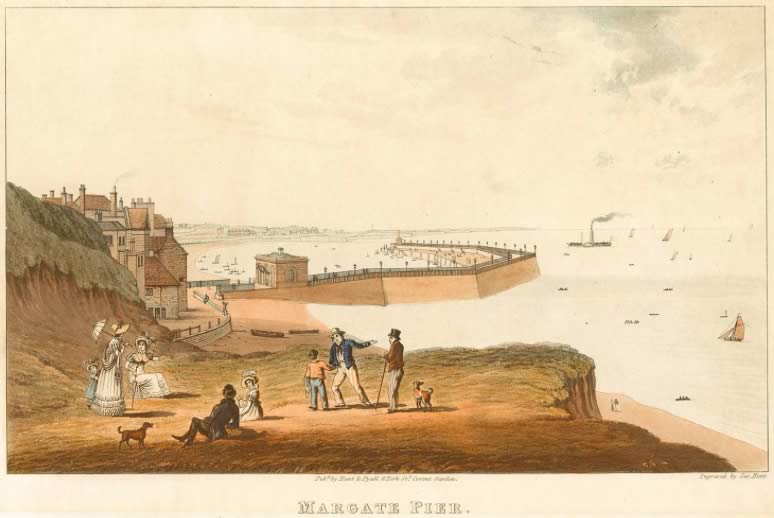

Beginning about 24 April 1817, Keats, aged twenty-one, goes to Margate after a week on the Isle of Wight. The island seems not to have turned on his poetic tap. He hopes Margate will. He will stay a few weeks, and after visits to Canterbury and the area around Hastings, he will be back in Hampstead by the second week of June.

Keats has stayed in Margate before (in August/September 1816), where he managed to

write a

few epistle poems about his mad

poetic ambitions and uncertain poetic intentions. Now,

in this second visit to Margate, his poetic trials and tribulations continue: he writes

to his

friend and unofficial mentor Leigh Hunt that, while

on the Isle of Wight, he thought so much about Poetry so long together that I could not get

to sleep at night

—not to mention that the food was bad (10 May). At this moment and in

this letter, we might want to imagine a young, inexperienced poet attempting to impress

an

older, experienced poet with his commitment to and passion for their shared art; yet,

with

measured humility, he worries about his poetic worthiness and uniqueness; Hunt is

less worried

about his own poetic talent. And so, as we will also see, the younger poet at the

same has

some emerging doubts about the older figure’s inflated sense of his poetic worth.

Letters from

Margate also show that Keats is somewhat obsessed with fame—whether he might attain

it,

whether he might be worthy of it, and what it means. He has concerns about what, in

light of

his somewhat uneven temperament, he calls his ultimate Progression

(to his publishers,

Taylor and Hessey, 16 May).

Keats has just begun work on what he projects as a 4,000-line poem, Endymion, based mainly on material—a narrative— from Lampriere’s Classical Dictionary. A first draft takes him to end of the year to produce, with a few more months in early 1818 required to copy, correct, make revisions, and (with some difficulty) fashion a Preface that almost invites slamming the poem. Endymion appears as a separate volume in April 1818, published by Taylor & Hessey. By the second week of May, Keats is, understandably, daunted by the task he has set for himself.

The idea to write a long poem emerges less from a creative impulse than Keats’s need

to prove

that he is, so to speak, made of the right poetic stuff. While conceiving Endymion in this spring of 1817, he writes to his brother, George, that he sees it as a test, a trial of my

Powers of Imagination and chiefly of my invention. [. . .] I must make 4000 Lines

of one

bare circumstance and fill them with Poetry [. . .] it will take me but a dozen paces

toward

the Temple of Fame [. . .] a long poem is a test of Invention which I take to be the

Polar

Star of Poetry

(Keats quoting himself in a letter of 8 Oct 1817). The poem’s achievement

(barely a few steps toward fame) may be modest, even if the poem’s length (4,000 lines

from a

bare circumstance

) is not. Writing the poem is less an act of inspiration and rather

more an act of perspiration.

Keats nonetheless claims that he likes the idea of a poem wherein a reader can wander

happily

among numerous enjoyable images—food for a Week’s stroll in Summer,

he writes. This

artistic position of creating fanciful, entertaining, and leisurely poetry formulated

in the

spring of 1817 (aligned to Hunt’s credo of poetic

sociability) is very far from the goals Keats begins to develop and embrace by the

end of the

year. It is, in fact, in some ways opposite to Keats’s much more serious, complex

idea of

Shakespearean Negative Capability,

and that poetry requires something to be

intense upon

(letters, 21/27 Dec 1817), rather that the experience of light, strolling

pleasantries.

By the end of May, then, some progress is made on Endymion, but, as noted, behind his work

is that lurking and confusing subject of poetic fame. From Margate he writes to Hunt, who, into the early half of 1817, remains Keats’s

unofficial mentor: I have asked myself so often why I should be a Poet more than other Men,

seeing how great a thing it is,—how great things are to be gained by it, what a thing

to be

in the Mouth of Fame,—that at last the idea has grown so monstrously beyond my seeming

power

of attainment [ . . . ] Yet ’tis a disgrace to fail, even in a huge attempt; and at

this

moment I drive the thought from me

(10 May). The obsession with the laurels of fame, in

fact, largely comes from Hunt; but, unlike Hunt, Keats is less certain about his destined

greatness and inherent superiority.

At this point in his writing career, then, with his indifferent and clearly immature

1817

collection behind him, and with the prospect of a long, undetermined poem ahead of

him, Keats

has some doubts. To his close friend, the painter Benjamin Robert Haydon, he writes that the Cliff of Poesy Towers above me

(10-11 May). To George, in the context of

explaining his need to write Endymion and in defining his

identity as a poet, Keats uses the same metaphor: the high Idea I have of poetic fame makes

me think I see it towering to [sic] high above me

(Keats quoting himself in the letter

to Bailey, 8 Oct 1817). Clearly Keats is

overwhelmed, if not confused, by ideas of poetic aspirations and accomplishment. Beyond

the

obvious problem for Keats—How do I become a poet?—lurk other questions: Why do I

write poetry, and for whom? And what is to be my subject?

Well before completing Endymion, Keats begins to recognize the poem’s indifferent qualities: My

Ideas with respect to it I assure you are very low— [. . .] I am tired of it

(letters,

28 Sept 1817). When completed, and when he begins to maturely assess his own strengths

and

weaknesses, he realizes the poem is largely a slipshod

and failed effort, yet necessary

for his own poetic progress (letters, 8 Oct 1818). By August 1820, after he has written

his

best poetry, he looks back upon it with the wish he could unwrite

it (letters, 18 Aug

1820).

What becomes clear during this period is that Keats feels something akin to periods

of

profound anxiety-depression: to Haydon he

writes, truth is I have a horrid Morbidity of Temperament which has shown itself at

intervals—it is I have no doubt the greatest Enemy and stumbling-block I have to fear—I

may

even say that it is likely to be the cause of my disappointment

(11 May). And to his new

publishers Taylor & Hessey he confesses, I have a swimming in my head and feel all

the effects of a Mental debauch, lowness of Spirits, anxiety to go on without the

power to

do so, which does not at all tend to my ultimate progression

(16 May). It seems this

state comes and goes throughout his adult life; that is, it is periodical rather than

sustained. Is it a medical condition (disorder) in the modern sense? The answer is

probably

no, since his state of lowness and anxiety actually have clear causes; true disorders

normally

don’t.

Importantly, perhaps with the prodding of Haydon, Keats at this time begins to note Hunt’s self delusions

of greatness—greatness as a poet, that is (letters, 11

May 1817). Nevertheless, Keats personally praises Hunt for the journalistic and political

edge

of The Examiner (letters, 10 May). This is a quiet turning

point, since it is only in late March 1817 that Keats writes a poem that praises Hunt’s

most

famous poem, The Story of Rimini, a work that, certainly for

the worst, influences Keats’s earlier poetry. Keats in his sonnet mentions the sweetness

and

delights in Hunt’s poem, the lingering and the leafy bowers, as well as hopping robins—just

the kind of characteristics and poetic props that Keats in fact needs to avoid in

his crafting

of his own progress as a poet. Clearly, Haydon and Keats trust each other with their

opinions.

It was, after all, Hunt who introduces Keats to Haydon.

The stay in Margate can be reduced to a fairly glib assessment: letters from Margate

once

more make it clear that Keats is anxious over whether poetry (that is, being a poet)

is really

for him—whether, in short, he is up to it. He will, nevertheless, and in a dogged,

determined

way, get on with that project poem, Endymion, which he will eventually

subtitle A Poetic Romance, and further preface it an epigraph on the title page with

a quotation from Shakespeare’s sonnet XVII: THE STRETCHED METRE OF AN ANTIQUE SONG.

Stretched, indeed—after all, how much can you do with the moon falling in love with

a

shepherd? And, for what it is worth, and if Shakespeare is to be quoted accurately,

THE

should read AND.