21 November 1817: The Reynolds’ Residence, An Expanding Circle, & Not All Experiments Work

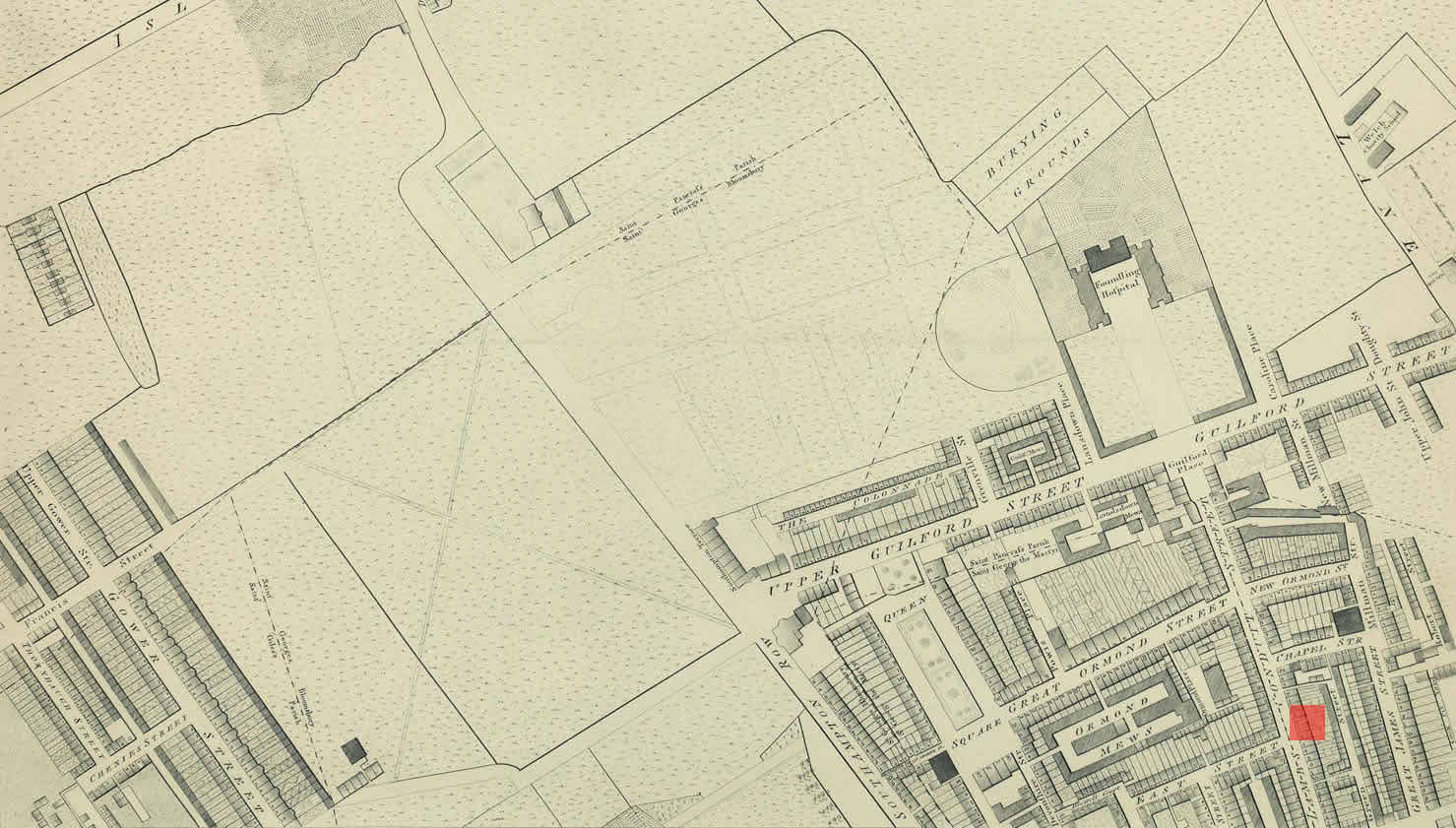

19 Lamb’s Conduit Street, London

The Reynolds’ residence: Where Keats dines, and where he becomes acquainted with an even larger network of persons in social, literary, and artistic circles. Keats is very good friends with John Hamilton Reynolds, having met him via Leigh Hunt in October 1816.* Keats is also at this time on very good terms with the family, and particularly the four Reynolds sisters. James Rice, Jr., who becomes Keats’s much-liked and generous friend, is also at the Reynold’s residence on the 21st, along with Jonathan Christie, who has connections with Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, a conservative miscellany magazine. Apparently they converse about ghosts.

Keats, who has just turned twenty-two, sees much of the Reynoldses at this time. Reynolds is, like Keats, a young poet, but also a significant reviewer and sometimes essayist for The Champion, though he is being articled in law (paid by Rice, who was also in the law business). Reynolds is just about a year older than Keats, but more experienced within London literary scene. Reynolds quickly introduces Keats to a numbers of persons who become important for Keats, including Charles Brown and his future publishers, John Taylor and James Hessey. No doubt Reynolds and Keats speak much about poetry, though Keats’s genuine feeling that poetry and poetry alone is his higher calling differs from Reynolds’ more practical and diverse aspirations. Reynolds no doubt also realizes that Keats’s poetic gifts surpass his own. Reynolds and Keats are also forever joined in literary history by Hunt, who, in a short piece in The Examiner in December 1816, names them as new, young poets to watch (Percy Shelley, also Hunt’s friend, and with whom Keats is acquainted, is likewise named). Keats will publish some poetry in The Champion, as well as a few reviews, standing in for Reynolds.

In hindsight, Christie’s presence at this

gathering carries a complex and tragic irony. Christie, in a duel in 1821, mortally

wounds

John Scott, editor of The Champion and then, by early 1820, The London

Magazine. Christie does so acting in defense of his longstanding friend, critic John Gibson Lockhart, who severely—and anonymously,

as Z

—attacks Leigh Hunt and then Keats (as

part of the vulgar, pretentious, and culturally dangerous Cockney School of Poetry

) in

a series of nasty essays in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine.

To reduce an extremely complex and cock-eyed narrative: By November and into December,

in

London Magazine, Scott fashions strong attacks and

counter-attacks on what he feels is Blackwood’s scandalous

dishonesty, though Lockhart is not named until a January 1821 article. Christie attacks

Scott’s personal character, in defence of his friend, Lockhart. Christie is challenged,

and a

series of confused communications fly between all concerned, including respective

lawyers.

Scott, aged forty, eventually dies of a stomach wound in the late-evening duel, though

the

duel itself is confused in its actions and protocols (it may not have been clear that

Christie

fired his first shot into air, thus making the duel null and void). Christie and those

involved are cleared of any charges. This may be a little hard for us to imagine:

someone is

killed in a duel over what reduces to literary tastes and reputation, and Keats, along

with

his friend and early mentor, Leigh Hunt, are central to reasons for the duel. [See

16 February 1821 for more on the duel.]

In fact, it is in October that the first of Z’s eight articles on the Cockney School of Poetry appears. Because of his perceived close association with Hunt, Keats expects to be attacked soon, but he will in fact have to wait until September 1818 for him and his poetry to be completely ridiculed and for the public coupling with Hunt to be publicly fixed.

At this point, Keats works on his very long (and largely unsuccessful) poem, Endymion. He completes a first draft at the end of November, having begun the poem in late April. Keats realizes its limitations, and more complex speculations about the imagination and poetry are just around the corner. Keats’s close examination of his long poem is a turning point in his own poetic progress, since he comes to see failings in the poem’s style and topic—and sense of purpose. Perhaps the most interesting feature of the poem is Keats’s attempt to experiment with certain set rules of metrics: he pushes the heroic couplet to its expressive limits, mainly by the use of enjambed lines that break down (or break open) the constrained, closed Augustan couplet, and in doing so, Keats sounds a kind of challenge to tastes that are infused with cultural and political values; the poem, though, is proof that not all artistic experiments work perfectly. More than anything else, though, Endymion does prove Keats’s dedication to poetry—it is an act of perseverance rather than of accomplishment. Keats’s attitude (and realization) becomes clear: I may need to write indifferent poetry in order to write great poetry. It is, then, at the same time a transitional poem (something to move forward from) and an endpoint (something to leave behind). The rather cringing but brave Preface he writes for the poem makes this clear. [For more on the Preface, see 7 April 1818.]

The next day, 22 November, Keats will compose an important letter. He writes to My

dear

Benjamin Bailey, with whom he has stayed at

Oxford in September and over into October, and has had sustained conversations about

literary

and philosophical matters while working on his Endymion. After wishing that Bailey knew all

that he thought about Genius and

the Heart,

and after expressing how much he trusts Bailey knows about his innermost

breast,

Keats rambles forward and variously—but acutely so, over topics crucial to his

thinking about the endgame of poetry, and measured in terms of his own character and

poetic

life; that is, the letter’s probing speculations come to anticipate and guide his

poetic

maturation. The emerging terms of reference are clear enough: the necessarily undetermined

character of Men of Genius

; the authenticity, power, and truth of the creative yet

careful imagination as a way of knowing, and this kind of knowing as essential Beauty

;

the limitations of consequitive thinking

as a means to or form of truth; the necessary

coupling of sensation and thought (though, for Keats, a momentary desire for a life

of the

latter in a world of uncertain happiness). Since these ideas play out in his greatest

poetry

(that is, in his poetry to come, mainly in 1819), one conclusion in terms of his poetic

progress is clear: Keats makes breakthroughs in his poetics before he makes them in

his

poetry.

[*See this flowchart for Reynolds’ key placement as a node in Keats’s social network.]