18 November 1817: Percy Shelley & Keats’s (non)Political Poetry

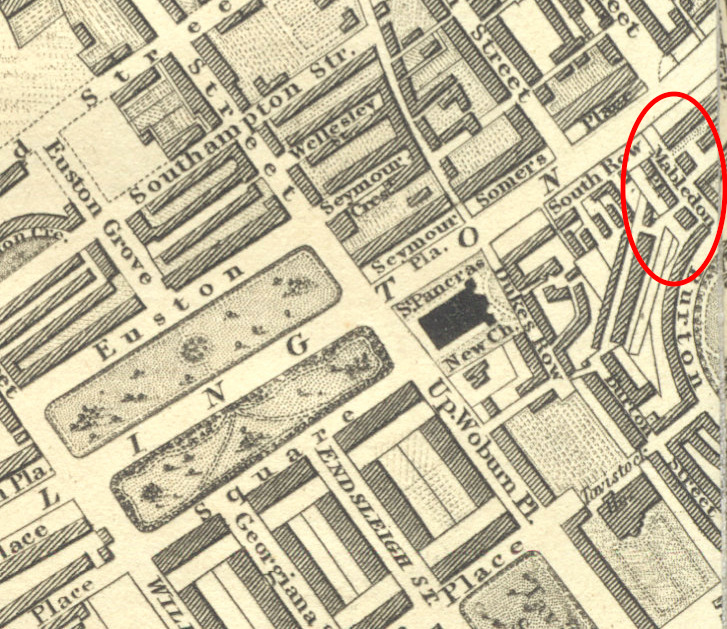

19 Mabledon Place, Islington

This neighborhood was not developed in 1799

Where the Shelleys (Percy and Mary) stay between 8-24 November, and are visited by Keats (just turned twenty-two) and poet-publisher Leigh Hunt. William Godwin, the famous novelist and social philosopher (and Shelley’s father-in-law), is also present. Like Keats, Shelley (born 1792) is a young poet, and the two are forever paired as canonical second-generative Romantic poets.

Shelley at his point considers Hunt one of his closest friends and strongest supporters of his work. In the course of their friendship, Shelley loans Hunt a considerable amount of money, as he does Godwin.

Keats, it seems, does not care for Shelley as much as Shelley for Keats. Certainly there are significant dispositional and class differences. Moreover, Shelley is much more outspoken and outwardly driven by generally radical, reformist politics. There also seems to be some implicit competition between the two young, aspiring poets, as well as (at least initially) some vague competition for Hunt’s sympathies. Each later criticizes the other (in a measured and civil way) for publishing immature verses. Shelley in July 1820 generously invites Keats to Italy when he hears about Keats’s consumptive state.

One of Shelley’s greatest and most complex

poems, Adonais (published July 1821, and considered by Shelley

as perhaps his best work) is ostensibly about the death of Keats, though the pastoral

elegy

(with its complex classical roots and dense allusions) also reflects upon a few of

Shelley’s

favorite subjects, including mutability, immortality, inspiration, and the striving

importance

of art itself—not to mention a little self-serving self-depiction in aligning himself

with the

greatly misunderstood young genius of John Keats. In Adonais,

Shelley also wants to demonstrate to Keats’s detractors that Keats as a poet is in

the line of

Milton and Spenser, and is therefore worthy of enduring poetical status.

Shelley famously felt (and publicly declared) that Keats’s death was hastened by savage,

slandering, partisan reviewers: as Shelley writes in the preface to Adonais, Keats the young flower was blighted in the bud

by the reviewing

cankerworms.

In fact, into the Victoria era, part of the poetic mythos of Keats is

the cultural construction of him as the sensitive, beautiful, unacknowledged victim

of evil

forces. Shelley’s Adonais will itself be mocked by some of the

same quarters that attack Keats in 1818: in the December 1821 issue of Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, Shelley’s poem is ridiculed for

being unintelligible and full of random, excessive poeticisms. In the review (by

Odoherty,

aka William Magin), Keats is once more nominated as the Cockney poet of

silly pretension and indulgence, with verse rife with Cockney slang and vulgar

indecorums.

This, then, is the other side of Keats’s cultural construction. (For more on

Keats’s reputation into the nineteenth century, see 26 February

1821.)

But at this time in 1817, Shelley is involved

with writing a passionate and charged political pamphlet, An Address to the People on the

Death of Princess Charlotte,

which is on the subject of and need for radical reform.

When, on 8 July 1822 at aged 29, Shelley drowns in a sailing accident off the Gulf of Spezia, a copy of Keats’s last collection (published 1820) is found jammed into his pocket.

While Shelley’s poetry often openly platforms political ideas, this is much less so with Keats. Shelley often feels compelled to respond to particular events and particular politically-charged figures of the day, as he does, for example, with his Masque of Anarchy, written as a reaction to a specific event of violent political repression (the Peterloo Massacre of 1819). While some noteworthy critical work also heavily contextualizes Keats as a political poet, political expression is seldom on Keats’s mature poetic agenda. He would cringe to think that his best work might be reduced to an expression of contemporary politics, though a few maliciously witty contemporary critics managed to do so with Keats’s early poetry, but mainly with the intention to hitch Keats up to the hyper-political Hunt, who publishes and, in a way, discovers Keats. Yes, as some might insist, everything is political (including form, language, publishing venue, etc.), but this is to say very little.* Reduction of everything to the play of politics is exactly that—reduction. But there is a paradox in all of this: Keats’s poetical aspirations will take him to purposely resist writing poetry that openly wears its politics via, for example, its style and voice; but such resistance can, at some level, and with some over-determination, be read as political.

As Keats poetically progresses, his consistent, self-consciously fashioned goal (repeatedly articulated in his letters) is to write poetry that possesses lasting qualities—poetry that, for example, imaginatively joins the time-defying nightingale or the persistent, timeless mystery of a a Greek urn’s truthful beauty. That is, Keats aims to write poetry for beyond its time and immediate history—posthumous poetry—and his greatest accomplishment is, by his final year of writing, 1819, finally achieved. For example, the autumn he writes of in September 1819 is our autumn and all autumns (in a greater metaphorical sense) that have been and will come; it is a season in all lives; no matter how subtextually or extra-textually a critic decides to read the poem, or how many political events or economic theories or clandestine government practices of the time are thrown at and into the poem, it remains a perfectly ripe poem about the expansive profundity of ripeness, of ending and continuity, of stillness in process. When Keats seeks to emulate Wordsworth, it is for the older poet’s philosophical depths and his profound articulation of human suffering and loss—his attempt to see into the life of things; when Keats studies Shakespeare, it is the bard’s ability to articulate and embrace powerful yet conflicting truths that intrigues Keats; when he studies Milton, it is his epic vision of humanity and his striking power of description that demands Keats’s understanding. Keats knew much about contemporary politics (with his circle of London friends it could not be otherwise), but this is not what indomitably drew his creative energy and his reasons for wanting to be an poet. We have countless statements from Keats about what determines enduring poetry and the poetical character, and being politically relevant is not one of them. Admittedly, there is a period in Keats’s early poetry, just when he wants to impress Hunt with some notions of contemporary relevance—but it is a passing moment in his poetry progress.

Taking up much of Keats’s energy at the moment in late 1817 is a final push to complete

a

first draft of his very long poem Endymion (which he does by the end of the

month) and to tend to his younger brother’s (Tom) illness, which slowly worsens. At the beginning of the month, Keats mentions

that he has read about the astonishingly virulent

attack on Hunt in the October issue of Blackwood’s

Edinburgh Magazine, entitled On the Cockney School of Poetry

(letters, 3 Nov).

Keats, mentioned in the essay, believes he will be next in the firing line, though

it is not

until August 1818 that the eloquent wrath of Blackwood’s is

turned upon him and Endymion (noting its drivelling

idiocy

), with the Quarterly Review as equally damning

just weeks later. Endymion, then, comes off very poorly, though aspects of the criticism beyond

the bias of partisan politics is largely correct: Endymion is, too often, as J. W. Croker notes in the Review, random and wandering, and at too many moments seems not much more than a

wearying and immeasurable game at bouts-rimés.

* One is tempted to dredge up Lionel Trilling’s complicating view (and warning) from

the

introduction to the 1946 Partisan Reader: Unless we insist

that politics is imagination and mind, we will learn that imagination and mind are

politics,

and of a kind we will not like.