November 1815: The Mathew Family

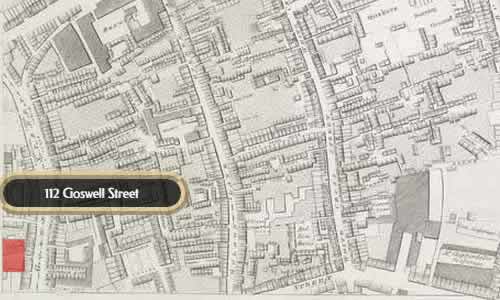

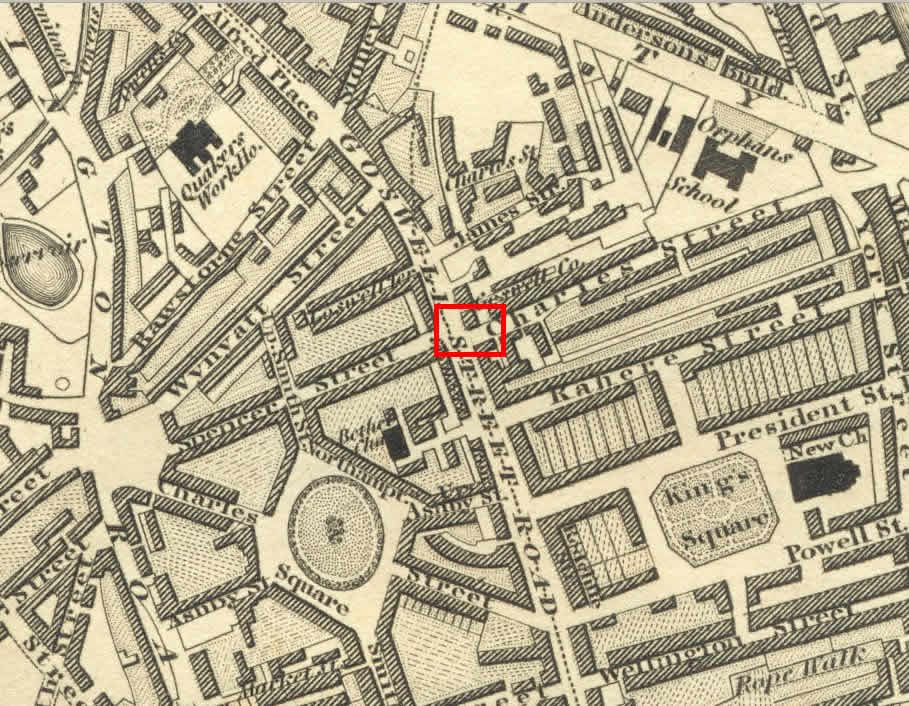

112 Goswell Street, London

Home of the four Mathew sisters, met through one of his younger brothers, George. Through two of the sisters, Caroline and Anne, Keats meets their cousin, George Felton Mathew. Keats writes inconsequential early poems to the sisters: To Some Ladies, On Receiving a Curious Shell, and Woman! When I behold thee . . ., all of which end up in Keats’s first collection, Poems, by John Keats, published in March 1817. Keats, it seems, covers the cost of publication, which is not usual for an unknown writer, and also given the inexperience of his publishers.

With his brothers, Keats does quite a bit of suburban-styled socializing at the Goswell Street residence around the summer of 1815l and later into the year, with Keats making some impression with, perhaps, his more intensely physical and intellectual presence, as well has his more natural personality (that is, his less reserved nature). He was not really like the Mathew circle, and in a way, he might have been, so to speak, a novelty item within it. Keats would have met others of interest via the Mathews group, perhaps people, like John Spurgin, a budding medical student who was a Swedenborg ethusiast, and with whom Keats has some discussions about religious faith and fables.

For a short period, Keats is fairly close to Mathew, himself a budding poet; this must have interested Keats. They exchange poems

in 1815, and in October 1816 Mathew publishes a poem to Keats, To a Poetical Friend,

which encourages Keats to keep writing under the spell of the gay fields of Fancy,

and

to continue to tell of Fairies and Genii.

Keats writes an epistle poem to George in

November 1815 (To

George Felton Mathew), which suggests some shared reading by the two. Like many

of Keats’s verses at the time, the poem expresses Keats’s desire to write enduring

poetry; in

this case, he somewhat randomly imagines a kind of pastoral and embowered vision-space

where

he might sit, and rhyme

(56) on Chatterton, Milton, Shakespeare, Fletcher, Burns, Beaumont, Spenser,

and other immortal figures. But, with undertones of a different politics than that

of Mathew,

we can see the two friends’ perspectives beginning to show difference. In a way, then,

this

subject (and style) to a degree anticipates more ambitious (and slightly better) early

poems

like I Stood

Tip-toe, and Sleep and Poetry, in which Keats continues to imagine himself as an inspired

poet—though imagining being one is different that actually being one. Keats is greatly

in need

of a subject beyond an expression of infatuation with great poets and poetry.

Within a year or so, the enthusiastic friendship between Mathew and Keats slides, with Mathew perhaps feeling threatened by Keats’s growing aspirations—and poetic, critical knowledge. Or perhaps Keats feels he has himself moved beyond the more conservatively inflected capabilities of Mathew’s poetic interests. The latter will definitely become true as Keats moves up and into another, more liberal circle of established poets, writers, artists, and publishers toward the end of 1816—and at that point his poetic aspirations will be fully launched. At any rate, Mathew is left behind—but not before he later (in May 1817, in the European Magazine) publishes a somewhat prickly review of Keats’s first (1817) collection, in which Mathew draws some attention to the ineffectual and limp poetic influence of Leigh Hunt, who comes to be a new mentor after Mathew’s departure from the Keats circle. It is also clear that Mathew is not favourably disposed to Hunt’s politics—to, that is, reformist, republican sentiments. Mathew wants to believe that Keats’s best poetry thus far was written under his influence.

Over 1815, then, Keats broods over being a serious poet, and his poetry generally reveals not much more than this. He eventually moves away from the epistolary mode, though it at least allows him to explore a more natural voice, one less bogged down by cloying sentiments and pretension.

1815: the year Napoleon meets his Waterloo, William Wordsworth publishes his two-volume collected Poems, and Jane Austen’s Emma is published.