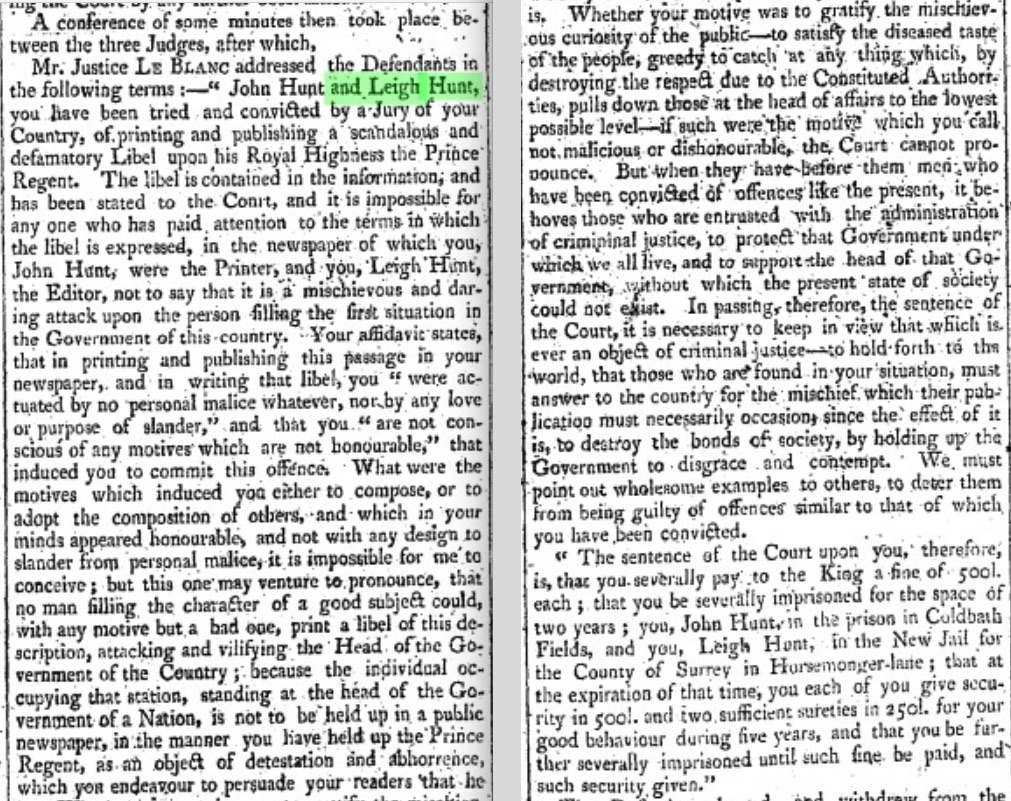

2-4 February 1815: Leigh Hunt Sentenced & Imprisoned: A Hero for Keats

Horsemonger Lane Gaol (Surrey)

Where Leigh Hunt, co-editor and writer of The Examiner, is imprisoned for (officially) seditious

libel

of the Prince Regent. Hunt is imprisoned for two years, beginning February 1813,

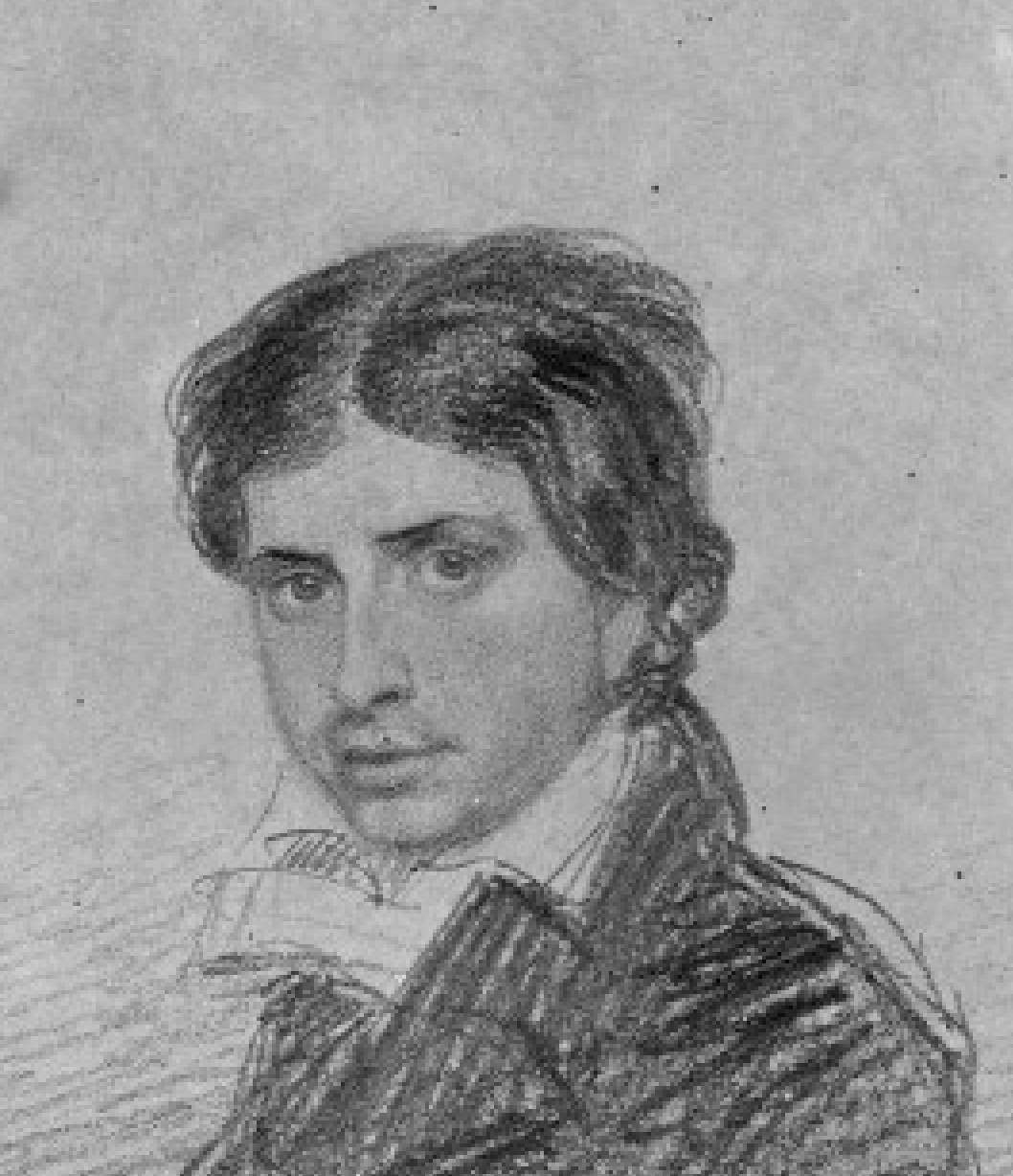

and his celebrity status—as a reformer, journalist, editor, poet, independent thinker,

and the

centre of a kind of artistic and political coterie—grows with his imprisonment. John Hunt, Leigh’s brother and proprietor of The Examiner (but often titled as the journal’s printer) is also

jailed, though elsewhere. Both are fined 500 pounds—a sentencing that reflects the

judicial

political sentiments of the day.

Although initially conditions in Horsemonger Lane Gaol in Surrey are difficult (involving his wife and two children staying with him), by April 1813 Hunt is given more room (in an infirmary area) and access to a garden; and, as a subtle act of resistance to the political forces that put him in jail, he consciously fashions a kind of salon, library, and receiving area for his many and continuous guests, a number of them famous—e.g., Charles Lamb, William Hazlitt, Sir John Swinburne, Jeremy Bentham, Henry Brougham, Thomas Moore, John Scott, Maria Edgeworth, Benjamin Robert Haydon, and Lord Byron. Hunt manages to decorate his prison digs with pictures, blinds, bookcases, musical instruments, couches, vases, and flowered wallpaper, and he also delightfully cultivates the garden space. Nevertheless, later separation from his family, his children’s illness, and financial issues plague him, while he still keeps up with his work on The Examiner.

As suggested, one side effect of Hunt being imprisoned was to focus even more attention on Hunt as the centre of wide grouping that will, by some, be denounced as the Cockney School (of both politics and poetry). Hunt, however, will eventually come to be proud of his Cockney nomination, since it branded him apart from other, more repressive and conservative forces of his age. For better and sometimes worse, then, Hunt always saw himself as an independent outsider, ready to figure himself as the embodiment of dissent; this also becomes entangled with a brand or style of Huntian aesthetics that (not always successfully) challenges the established genteel with what others would see both impertinent and vulgar. Because Keats’s early education (at the dissenting Enfield Academy) revolved around the nurturing of free-thinking, Hunt’s circle was a natural fit for his symathies and values.

On 2 February 1815, Keats—who had never met Hunt,

but was aware him even as a student at Enfield—writes a sonnet to celebrate Hunt’s

release

from prison: Written on the Day That Mr. Hunt Left Prison. In the poem, Hunt’s fame,

immortality, and genius,

as channeled through Spenser, Milton, and even the

sky-searching lark,

will never be impaired by his detractors—so croons the young Keats.

Keats will sing a different tune by mid-1817.

But in 1815 over into 1816, Hunt is a living martyr, model, and hero for aspiring Keats, which would be understandable given Keats’s age, lack of experience, limited connections, and (via his schooling at Enfield) his attraction to freethinkers. And no doubt Keats’s first genuine poetic mentor, Charles Cowden Clarke, talks to Keats about Hunt, and he certainly praises Hunt’s progressive, independent voice (Clarke had visited Hunt in jail). After Keats meets Hunt in October 1816 through Clarke, Hunt also becomes a close friend and assumes the role of Keats’s mentor—Hunt recalls that the two were instantly intimate. Life at that point changes for Keats. [For more on Keats’s meeting with Hunt, see 10 October 1816.]

Extraordinarily important in terms of Keats’s poetic progress, Hunt almost immediately introduces Keats into a remarkable network of important friendships and connections—writers, artists, poets, journalists, critics, scholars, lecturers, and publishers. Despite Hunt’s support and reputation, after 1816 it does not take Keats long to realize that Hunt’s diverse and uneven literary qualities as a poet limit his own abilities and aspirations, and that Hunt’s self-assessment as great poet is inflated, if not, according to Keats, a little delusional.

For his part, Hunt will not mind being viewed as Keats’s mentor, given that he clearly recognizes Keats’s considerable poetic potential; and, in truth, we could say that Hunt both discovers and promotes Keats—Hunt is the first to first publish Keats, in May 1816 in The Examiner (O Solitude). But association with Hunt also ends up publicly pigeonholing Keats as a mere Huntian devotee, and thus a producer of the kind of poetry (of suburban sociability and good cheer, of fancy, of poetry for its own sake) disdained in certain influential reviewing circles. Moreover, connection with Hunt pegs Keats politically, squarely putting him on the liberal/reformist side of the question, though Hunt’s politics might best be characterized as independent. Keats will want much more from the poetical character he goes on to develop over the following years; he will want more than vague social or political relevance. A few of Keats’s closer friends (whom, ironically, he meets through Hunt) will urge Keats to uncouple himself from Hunt’s influence. In short, although Keats’s political sympathies generally align him with Hunt, Keats strives to have his own poetics and poetic development not revolve around or directly address the contemporary political scene. Keats is thinking bigger, greater, deeper.

So in writing his Ode to

Apollo this month, we see first hints of Keats finding ways to parade his

poetic predecessors, basically just by listing them and providing somewhat saccharin

annotations of their poetic worth: Homer

(twanging harp

), Virgil (sweet majestic

tone

), Milton (tuneful thunders

),

Shakespeare (inspiring words

),

Spenser (Wild warblings

), Tasso

(ardent numbers

)—all golden bards with solid rays and twinkle radiant fires

(5). Yes, Keats wants to be just like them.