20 March 1810: His Mother Dies, & What Death Means for Young Keats

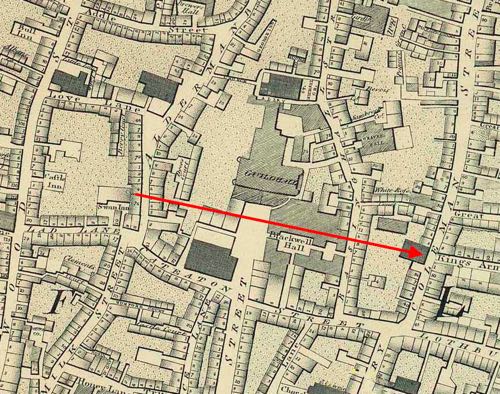

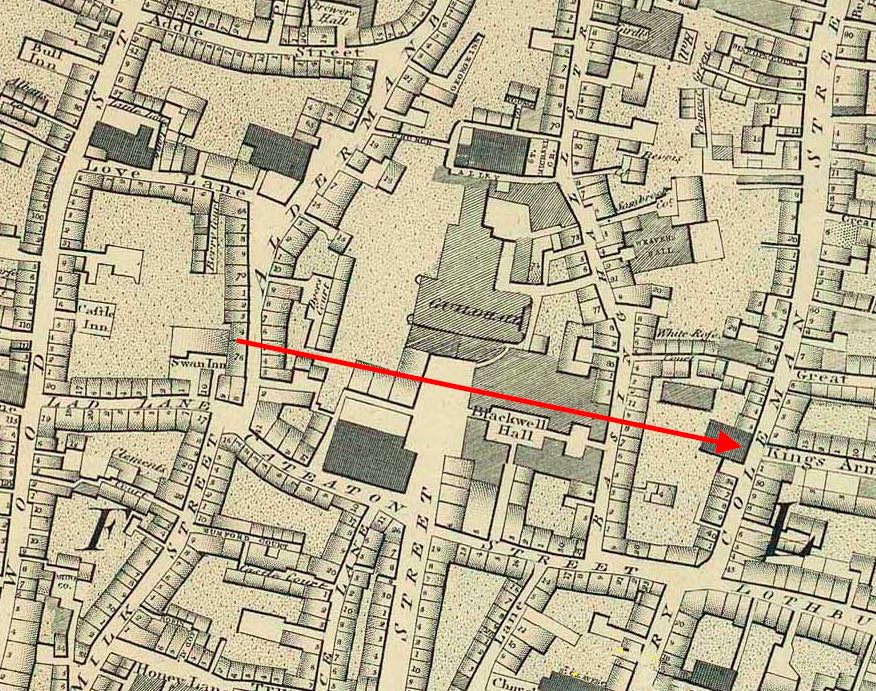

St. Stephen’s Church, Coleman Street, London

I have never known any unalloy’d Happiness for many days together: the death or sickness of some one has always spoilt my hours— (Keats, letter to Fanny Brawne, 1 July 1819)

Keats’s mother, Frances, aged 35, dies of

tuberculosis, which at the time was often officially recorded as a decline.

The illness

also eventually takes all the Keats brothers: Tom in 1818; John in 1821; and George in

1841. Frances is buried at St. Stephen’s Church, Coleman Street, on 20 March 1810.

Fourteen-year-old Keats would have been devastated by the death of his mother, having

witnessed the final, agonizing stages of her decline, and, when possible, attending

to her.

Tuberculosis does not offer an easeful death, and because, at the time, it was thought

of as a

family complaint,

and therefore hereditary, Keats might have conjured some darker,

fatalistic views.

So, over the period of about six years, Keats has lost his father (1804) and his grandfather (1805), and now his mother—he had also lost his two uncles on his mother’s side, and he knows little of his father’s family of origin.

Keats, then, as a young teen, is an orphan, and things would never be the same.

How were things kept together?

A saving feature during Keats’s pre-adult years is the loving stability offered by his maternal grandmother, Alice Jennings, both before and after his mother’s death. A further securing presence for young Keats is his boarding school at Enfield (Clarke’s Academy): it provides the initially boisterous yet emotionally sensitive Keats with some guidance and continuity, and then the maturing and more studious Keats with friendships, opportunities, and a library for the increasingly book-passionate lad. Importantly, the dissenting school also shapes Keats with values springing from the school’s declared outcome to develop free-thinking and notions of liberalism and civil liberty. Further, the headmaster’s son at Enfield School, Charles Cowden Clarke, eight years older than Keats, will eventually make the pivotal connection in Keats’s writing career: Clarke, who is clearly impressed with young Keats, and who takes the time to tutor Keats’s tastes and interests in music and literature, will go on to introduce Keats to celebrity journalist, poet, critic, and publisher Leigh Hunt, in October 1816, which immediately launches Keats into a circle of poets, artists, publishers, critics, scholars, and writers.

The final prop for orphaned Keats is the presence of and his closeness to his siblings, though contact with his young sister, Fanny, is compromised by her protective ward, Richard Abbey, who is also the manager of the family estate.

We cannot be certain if there is a causal connection between the death of his mother and a growing interest in poetry, though by 1814—the year his dear grandmother Alice passes, aged 78—there is evidence Keats is composing poetry. In fact, the first of Keats’s very early writing that attempts some depth is a sonnet on the death of Alice—As from the darkening gloom a silver dove—but the poem disguises its true subject, and then hides behind poetic cliché draped in too-obvious Miltonic and Spenserian phrasing. Unsurprisingly, Keats does not yet know how to represent his subject in a way that teases us out of thought. Keats will learn.

At this point we can speculate: the passing of his parents and maternal grandparents, relatively closely in time and so early in his life, perhaps contributes not just to Keats’s disposition that at moments struggles to contend with uncertainty and loss, but also to the formation of certain poetic ideas, ideals, and motivations. These will be expressed in subjects that range from the meanings of fame and ambition to suffering and immortality—and, significantly, translated into a deeper poetic consciousness of the play between life and death. Only after very deliberate study of, for example, Shakespeare, Milton, Dante, Homer, and Wordsworth will Keats come to poetically represent these topics in maturing, original, and complex ways, with the growing realization that occasional, chivalric, and romantic motifs the emerge via some of his early infatuations perhaps limit his desire to produce enduring poetry, or at least poetry that is more natural to him.

So as we gauge Keats’s progress, we will watch how, at certain points, he faces a key question: What subjects should occupy the mature poetic imagination?

[For information about the Keats family graves being relocated, go to 23 April 1804.]

[For more on Keats’s school and schooling, see Clarke’s school, Enfield.]