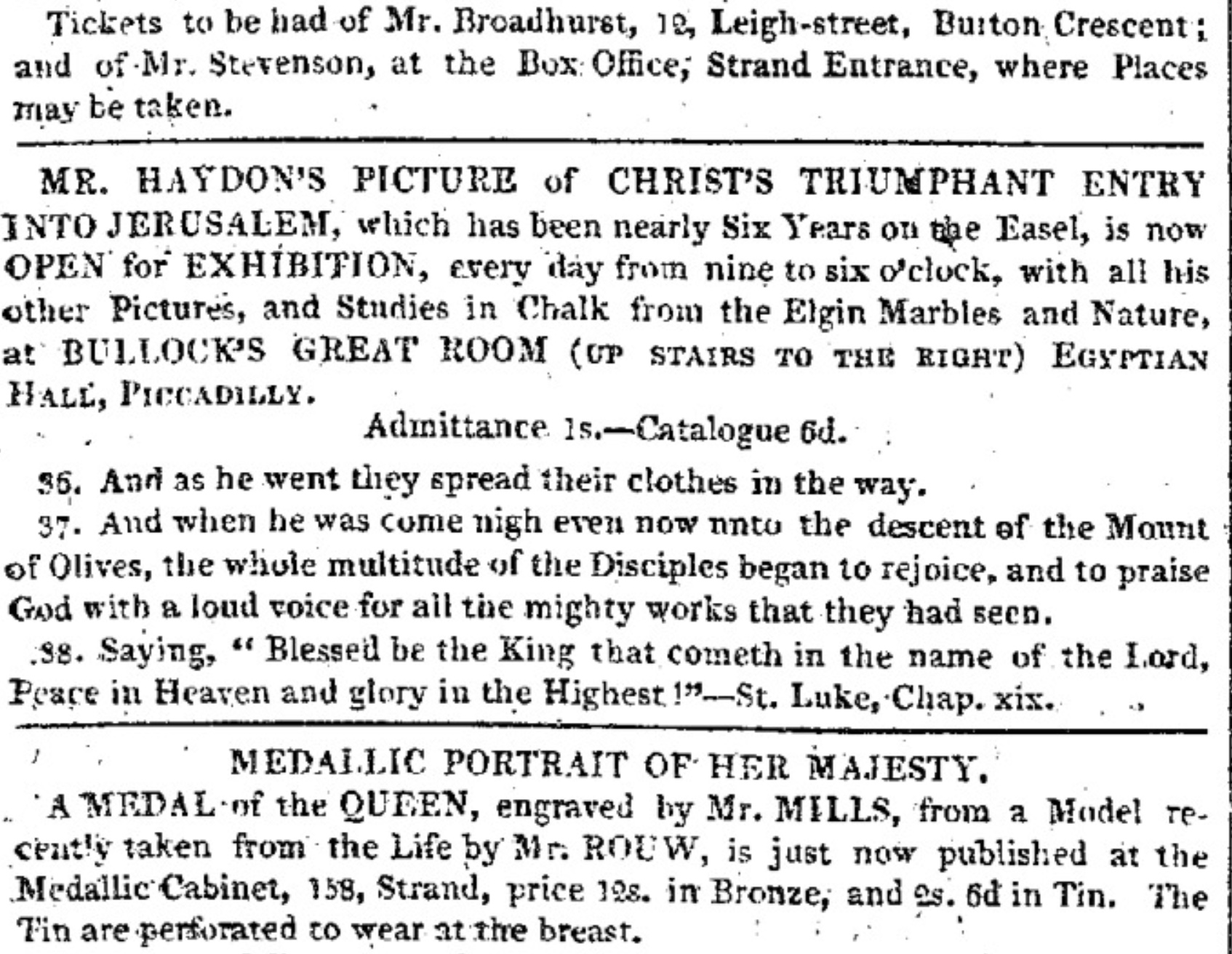

25 March 1820: Benjamin Robert Haydon, Christ’s Entry,

Anxiety, & the Desire to be

Remembered

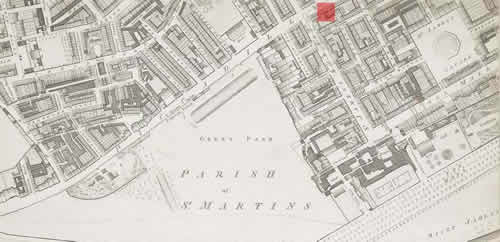

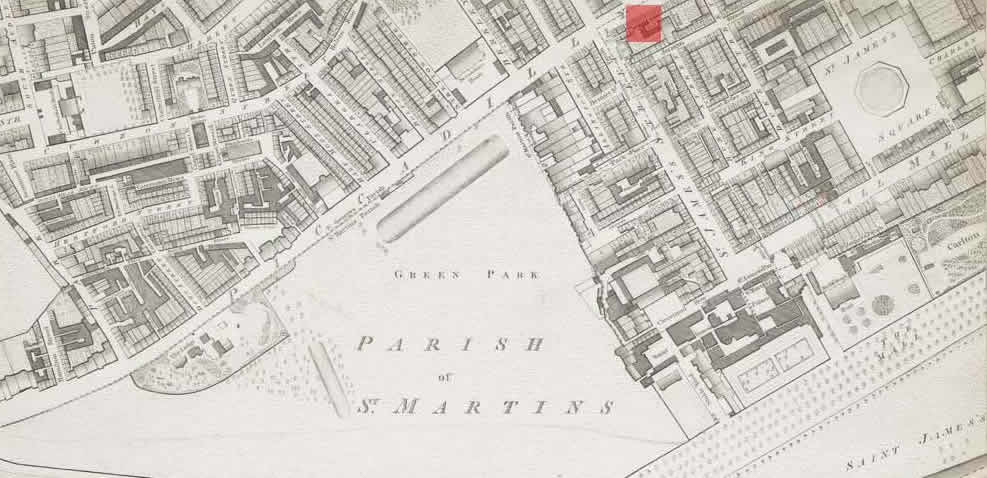

Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly, London

At a private exhibition at the Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly, London: Keats sees the completed

historical painting Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem,

a huge canvas painted (over a period

of about six years) by his good friend, Benjamin Robert

Haydon. The Egyptian Hall is demolished 1904-5; a Starbucks may currently be on the

site (about 171 Piccadilly). The painting is also known as Christ’s Triumphant Entry into

Jerusalem,

as it is advertised later in the year (see the ad below).

Six Years on the Easel: Haydon’s Christ’s Triumphant Entry into Jerusalem, The Examiner, 1 Oct 1820 (click to enlarge)

Keats, aged twenty-four, must have felt quite flattered by being included in the crowded

canvas, along with more famous contemporaries like William Hazlitt, William

Wordsworth, and Charles Lamb, as well as

historical figures like Voltaire and Newton. The painting gets a great deal of attention,

though Hazlitt’s reputation sinks over time; Haydon’s modest output and neoclassical style (the grand manner,

as it is

sometimes called) is at a certain point limiting and dated. And Haydon is, it seems,

a very

slow producer: this is good news and bad news: good news in that it seems he must

have taken

some care, and bad news, in that he needs complete paintings in order to sell paintings.

Keats’s relationship with Haydon begins in enthusiastic mutual admiration soon after they meet in October 1816 via poet, publisher, and celebrity journalist Leigh Hunt; it evolves to infatuation (and to something like brotherly love, even); but it wanes and strains over personal and financial issues into 1819, as Haydon pushes Keats for money, just while Keats himself struggles to stay afloat.

Haydon, almost ten years Keats’s senior, is a complex character: quarrelsome, sensitive, passionate, pedantic, a great conversationalist, boastful, at times emotionally unbalanced—with bad eyes and bad handwriting (but an excellent writer). No doubt he influences some of Keats’s tastes and values in art (and in particular the relationship between art and beauty); and, like Hunt, he also introduces Keats into aspects of London’s culture and to people. Haydon knew a lot of interesting people, and he thought a great deal about art’s larger purposes. He was a famous and extremely passionate defender of the controversial Elgin Marbles; and Keats, upon seeing the Marbles (initially with Haydon back in early March 1817) is spurred to very profitable and perhaps crucial consideration of how voiceless, wordless art can, centuries after its creation, still awaken profound thoughts and feelings—and will do so forever, without its perpetually changing audience knowing anything of its originating conditions: How can he, Keats, via poetry, also approximate such stilled expression and feeling? How can he create art that has such compelling, silent, staying power? This is central to Keats’s progress. Haydon also contributes to Keats’s turning away from Hunt’s influence, who is the other key figure in the early period of Keats’s writing career. Hunt and Haydon in fact compete a little over Keats’s loyalty and attentions. Sadly, after a failing career and continuing financial trouble, in 1846 Haydon commits a grizzly suicide: he manages to both slit his throat (twice) and shoot himself.*

For Keats, early 1820 is marked by numerous overlapping moments of uncertain mental

and

physical health. He is generally at a loss as he flips between idleness and restlessness.

He

is tired of some of his friends; he is tired of London; he is often too weak to do

much; he

has a fairly dire financial situation; has no new creative project. He is at times

confined

due to colds, fever, and, increasingly and most dangerously, chest issues. Keats may

be

experiencing something akin to panic attacks—in early March, his close friend Charles Brown will describe them as violent

palpitations at the heart

(8 March), though Brown apparently soon receives some hopeful

but utterly incorrect diagnostic information: as he writes to John Taylor, Keats’s

publisher,

we are now assured there is no pulmonary affection, no organic defect whatever,—the

disease is on his mind, and there I hope he will soon be cured

(10 March).

Yes: Keats, during this period, indeed suffers from emotional turmoil, with (in his own terms) fears, anxiety, impatience, discontent, and uncertainty; but the fact is that Keats for at least six months has been physically unwell, with his symptomatology repeatedly centered in his chest—the words inflammation, palpations, weakness, and tightness keep coming up. Perhaps at the back of all of this, consumption had set in earlier than 1820; his earlier nagging throat issues may have been a sign of something else. [For more on Keats and consumption and the connection to those throat issues, see 3 February 1820.]

Beyond the physical symptoms, Keats expresses to his friend James Rice that he is beginning to experience something like what we

today might call depression (14 Feb. 1820)—nervous irritability

and anxiety of

mind

are what a doctor tells him, and immobilizing feelings at moments plague him;

remarkably, the too great excitement of poetry

is also seen as a cause of his condition

(letters, 21 April). Keats even comes to fear having any negative thoughts at all

(letters, 4

May). That haemorrhage on 3 February is a sign that Keats himself recognizes as serious—in

fact, he immediately believes it might be a death-warrant.

Given Keats’s condition and

situation, which borders on being disabling, his intense feelings—especially in the

form of

fear and foreboding—are hardly surprising. Most of Keats’s friends are aware of Keats’s

dire

prospects; as Haydon writes to William Wordsworth 28 April, Keats is very

poorly, and I think in danger.

Keats’s diet is restricted (he is off animal food), but this treatment also weakens

him

(letters, 4 March). He is given strict orders to rest. He comes to consider the mind/body

connection: as he advises his younger sister, Fanny, low spirits [. . .] are great enemies to health

(12 April).

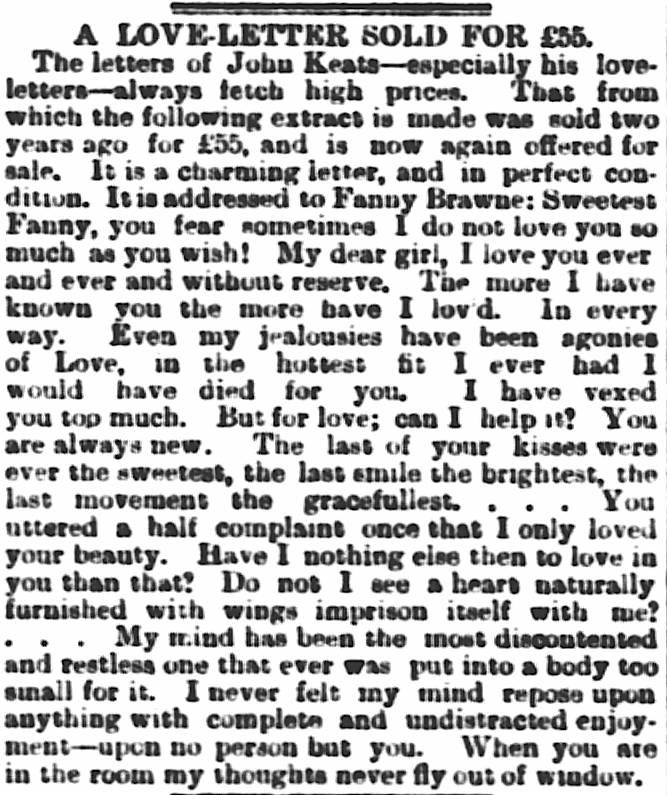

Complicating this period are strong yet restless feelings of love for Fanny Brawne, expressed in a number of notes to her, many in a

flurry over February and into March. He tells her that he thinks of little else but

her lips,

her kisses, her smiles, her embrace. With his health issues and precarious prospects

for

earning a living, he feels he can only be patient, and wait—but for what? What prospects

does

he really have? He has some vague but passing hope: Illness,

he writes to Fanny, is

a long lane, but I see you at the end of it . . .

. For a moment he considers breaking

his engagement to Fanny, though he makes it clear he cannot bear the thought of losing

her

(Feb 1820).

Given Keats’s complex feelings for Fanny, which

are agonizingly compromised by his inability to fully engage with her during this

period,

there is a good chance that Keats writes what might be his last full poem, though

its dating

remains a matter of conjecture. Ode

to Fanny has references to blood-letting (which happens after his 3 February

haemorrhage); to not being able to be with her (he is confined to rest); to emerging

jealousy

(that she socializes while he cannot); to his increasing possessiveness; to his desire

but

inability to write poetry (to conjure any poetic theme

); to his utter ravished,

aching

love for her (Fanny is, he writes, the sweet home of all my fears, / And

hopes, and joys, and panting miseries

)—these all point to the first part of 1820 as the

time of the ode being composed. The ode is decent, and it attempts poetic control

over its

emotional intensity, but the somewhat confused expression of personal desire intermixed

with

an awkward attempt to convey an elevated sense of the subject—his love for Fanny—compromise

each other. Ode to Fanny

remains touching and revealing as an expression of Keats’s declining situation, his

confusions, and his precarious love.

In a moment of feeling better, Keats makes some small revisions to Lamia, which will be one of the title poems of his

final collection, and the lead-off poem in the volume: Lamia,

Isabella, The Eve of St. Agnes, and Other Poems, published in June. Lamia, he believes, will have

some success, since it is written with some fire

in order to appeal to the public’s

desire for sensation

(letters, 18 Sept 1819). But he writes no new poetry. Keats hopes

to get on with publishing the collection, but he is too weak to do much of the work

or even

contribute a preface. In fact, what goes into the volume, how it is ordered, will

to a large

degree be out of his hands. Brown reports to

Keats’s friend and publisher, John Taylor,

Keats’s rather sad hope: He desires to be remembered

(13 March). Well, that much, at

least, he achieved.